Wet Plate Collodion

Wet-plate Collodion Negative

COLLODION NEGATIVE (wet-plate collodion), 1851-1885

Silver-based negative on glass with collodion (nitrated cellulose dissolves in ether and alcohol) as a binder to hold light sensitive materials

A solution of collodion and potassium iodide is poured over a glass plate leaving a clear film containing halide. The plate is then dipped in a solution of silver nitrate to form light sensitive silver halide on and just under the collodion surface. After being exposed in the camera while still wet (hence wet-plate), the plate is developed using pyrogallic acid (later ferrous sulfate), washed and fixed in sodium thiosulfate (later potassium cyanide). Once dry, the plate is coated with a protective varnish to prevent the silver image from tarnishing.

Hand-pouring of chemicals results in an uneven edge of the image on the glass. The corner of the negative where the photographer's thumb held the glass during coating remains chemical-free.

Mathew Brady. Ambrotype, late 1850s.

Quarter plate

The ambrotype process produces a collodion glass negative which, when viewed against a dark background, creates the appearance of a positive image. When viewed against a light background, however, the image is revealed as a negative.

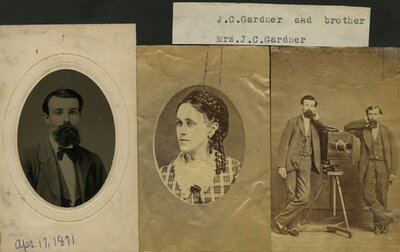

Unidentified. Page from the Gardner Family Album, ca. 1871.

Tintype (left), albumen prints (center & right)

Capturing an image with the 8 x 10 in. sliding-box camera (right) required the photographer to perform an uninterrupted series of tasks. He prepared the wet plate collodion plate in the darkroom, loaded the camera, and posed the subject. He then focused the image, exposed the plate by lifting the lens cover by hand for the required time, removed the plate, and brought it back to the darkroom for immediate processing.

On loan from the Stephan and Beth Loewentheil Family Photographic Collection.

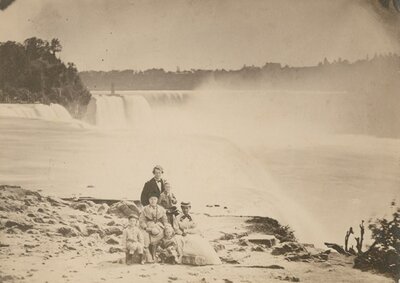

Samuel J. Mason. “Views of the Entire Falls with Yourself and Friends in the Foreground,” 1870s.

Albumen print, 5 5/8 x 8 1/8 in.

This photograph bears the hallmarks of an image printed from a wet plate collodion negative. The top corners of the negative remained chemical free where the photographer’s thumb held the glass during coating, resulting in a black corner on the positive print. The water shows no detail because of the slow shutter speed. Clouds do not appear because the wet-collodion process was sensitive only to blue light. While warm colors appear dark, cool colors such as the blue sky and white clouds are uniformly light.

Ambrotype

AMBROTYPE, 1855-1865

Silver-based, one-of-a-kind image on a glass plate with collodion as the binder to hold light sensitive materials

An ambrotype is essentially a collodion negative that is underexposed. The underexposed collodion has a creamy image tone. When placed against a dark background, the creamy image appears as the light tones of the positive image. The area without image particle (i.e. clear in the negative) shows the dark background and becomes the dark tones of the positive image. The black background is created in a variety of ways including coating the back of the glass with black lacquer, laying the glass on a piece of black fabric, or using dark glass, often called "ruby glass," instead of clear glass. As with collodion negatives, ambrotypes are often coated with a protective varnish.

Like a daguerreotype, an ambrotype is usually encased. Unlike a daguerreotype, it remains a positive image under all viewing angles.

Tintype

TINTYPE (ferrotype), 1856-1915

Silver-based, one-of-a-kind image on an iron plate with collodion as the binder to hold light sensitive materials

Similar to an ambrotype, a tintype is a wet-collodion process, but on a dark lacquered iron plate instead of glass. The lacquer forms the dark background required to reveal the positive image. Tintypes are often coated with a protective varnish.

Tintypes can be found in albums, carte de visite size paper mounts, daguerreotype cases and frames. It is often difficult to distinguish a cased tintype from a cased ambrotype.

Unidentified. Tintype, 1880s.

5 x 3 1/2 in.

Tintypes were less expensive, more durable and easier to produce than both ambrotypes and collodion negatives. Often used by itinerant photographers, tintypes were the closest approximation to instant photography in the 19th century. Tintypes first appeared in the United States in 1856 and remained popular well into the 20th century.