Exoticism and Exploitation

Although the circus provides an outlet for the audience to escape the trials and tribulations of daily life, it is important to acknowledge that with the fantasy comes the reality of the circus’s problematic history of exoticism, racism, and cultural appropriation in costume, representation, and imagery. Because the focus of this exhibition is on the costumes of the circus as well as their influence on the fashion industry, we believe it is essential to highlight the problematic histories around circus costume such as the appropriation and exploitation of non-Western cultural dress, the use of racist caricatures denigrating the Black community, and the lack of representation of non-white featured performers.

Preliminary research conducted to identify artifacts for potential inclusion in this exhibition started in the Circus Publicity Collection in the Division of Rare and Manuscripts Collections of the Cornell University Library. These items are mostly black and white photographs of circus performers from the 1950s through the 1970s, and as is the case with many archival items in collections, information about the people featured in the photographs is scant if not they were not previously identified. The majority of the aerial and tightwire publicity photographs in this collection feature white performers, and although there are a few non-white performers found in this collection, it is important to recognize that they do not exhaustively represent the diverse global cultures of the circus. This lack of diversity in archival collections of this type are all too common, and are demonstrative of the lack of featured BIPOC circus performers during this time period in the US.

PT Barnum's Ethnological Congress

This video is a part of the PBS Learning Media series "The Circus: AMERICAN EXPERIENCE", and is included as part of their licensing for educational purposes.

PT Barnum's Ethnological Congress is an example of the kinds of exoticism and exploitation experienced by people who did not meet his (or his audience's) perception of fitting in with the dominant culture. Locating the ethnological congress display in the menagerie tent situates the people on display as being on the level of animal, rather than human. There is a deep and complicated history of sideshows / freak shows that accompanied the main tent shows at the circus, and featured people whose bodies were considered different than those of the dominant, white Eurocentric culture.

Othering and Exoticism

Othering is the act of making a determination between groups, wherein the dominant group views the non-dominant group in such a way that differentiates, diminishes, or otherwise devalues its members and allows for the perception of “Us” and “Them” (Staszak, 2008). In the case of P.T. Barnum’s Ethnological Congress, this action dehumanizes the non-dominant groups and enables the dominant (Western, predominantly white) group to view themselves as the “Us” group. In doing so, there is a separation established where the “Them” group (in this example the people assembled and put on display by Barnum) is viewed not as human beings equal to the “Us” group, but rather as objects of curiosity to be scrutinized, touched, collected, and judged by the “Us” group as different.

In addition to the practice of Othering is the perception of people from cultures outside of the dominant group as exotic. Exoticism is defined by Staszak as “a taste for exotic objects/places/people” (2008, p. 1). Interpreted in this exhibition, exoticization is defined as the designation of value on something (such as a cultural mode of dress) or someone (a person from the non-dominant group) that is from outside the dominant culture, where the Otherness of the person or object is perceived as being of higher value than the person or item themselves. For example, by writing to US consuls in the execution of his plan to “collect” people he viewed as being from “uncivilized races”, Barnum placed himself in the dominant group, thereby Othering the people he was seeking to include in his Ethnological Congress. These people’s existence in races and cultures outside of Barnum’s perception of “civilized” established their value, in the exotic quality they possessed through their Otherness, rather than their value as human beings. Plainly speaking, their Otherness was valuable, and this value could be commodified.

Cultural Appropriation

Please note: The following paragraph contains links to images that may be disturbing, including photos of performers in blackface makeup and large costume masks that caricaturize Black and Middle Eastern persons, as well as performers dressed for the "Geisha Spectacle" production number of the 1933 Hagenbeck-Wallace Circus, and non-Native American performers in Native American dress. Additional links lead to essays and informative video, and all of the embedded links are included for illustrative purposes.

By removing symbols and practices of a culture from its context and population, and identifying these as Other, exoticized value is placed on the objects and symbols rather than the people and their cultures. Exoticization has been exemplified through the use of Native American dress as costume for non-Native performers, blackface makeup in conjunction with racist portrayals of Black people as objects of ridicule, using cultural dress such as Japanese kimono and makeup or movement to identify performers as Asian when they are not, and orientalist practices in the portrayal of Middle Eastern or North African characters or cultures. In all of the previous examples, value is placed on objects, caricaturized behaviors, and worn identifiers of a culture or race such as clothing or makeup rather than members of the culture or race themselves.

Race and Circus

History of Race and the Circus: The Gilded Age

Sakina M. Hughes explores the use of images in the portrayal of African American and Native American circus artists during the Golden Age of the American circus, or the 1880s to the 1920s. In this article, Hughes (2017) discusses the exploitation and perceptions of these populations as well as the agency held and demonstrated by performers, and the ways they subverted white supremacist practices. Expanding on the careers of Black male circus employees in the Gilded Age, Micah Childress (2016) examines the employment and labor practices of Black male and white female circus employees in detail, using primary sources for reference (which, unfortunately, results in quoting use of the N word a handful of times) to describe their living and working conditions. Not included in this discussion are Black female employees because “Outside of the rare Black performer or member of an ethnic display, Black men were generally given positions of manual labor, and shows did not hire African American women” (Childress, 2016, p. 177).

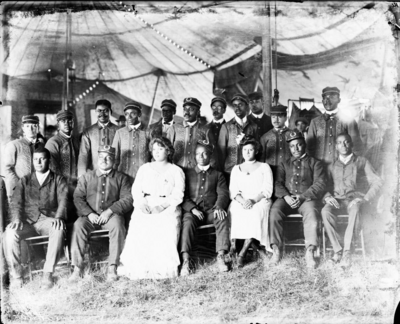

However, as Hughes (2017) demonstrates, Black female performers did make appearances in touring circuses during the Gilded Age, as is evidenced by the appearance of three Black female singers in a photograph of the P.G. Lowery Side Show Band in 1913 (Hughes, 2017, p. 326), although most major circuses in the US did not feature Black performers as headliners (Davis, 2002). It is important to note that Childress’s (2016) text is centered on the American circus which was to an extent (albeit perhaps marginally less so) reflective of societal opinions and the racism that so pervaded prevailing attitudes, and is as such not representative of the experiences of Black circus performers in other countries such as those discussed in Vanessa Toulmin’s (2018) article Black Circus Performers in Victorian Britain.

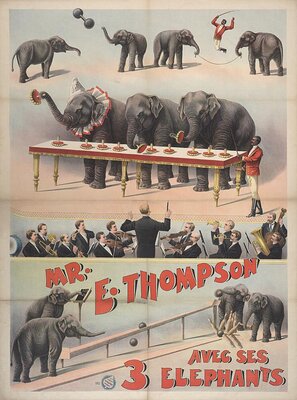

Moses Ephraim "Eph" Thompson

One such performer, Moses Ephraim (“Eph”) Thompson, was an animal trainer who joined the circus in the US and moved to Europe where he developed a storied career, holding featured positions in circus as an elephant trainer and presenter, rather than being hired for the sideshow or the band, as was more common in the US (Toulmin, 2018). This promotional poster for "Eph" Thompson's act depicts him in a dynamic pose, playing jump-rope with his elephants in the top right corner of the image, and directing the elephants in a game at the center. The text "Mr. E. Thompson avec ses 3 elephants" translates to "Mr. E. Thompson with his 3 elephants". This image is provided with permission from the John and Mable Ringling Museum of Art, and can be found here in their online collections.

In the video below, Mr. Harlin C. Kearsley describes the life of "Eph" Thompson, as well as circumstances surrounding race in the circus for workers and performers during this era. Mr. Kearsley graciously provided permission to use this video of Moses Ephraim "Eph" Thomson, which was developed as part of his African American History is AMERICAN History (AAHIAH) Video Series Channel on YouTube.

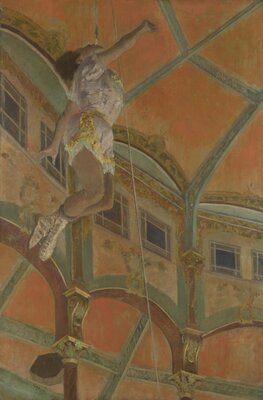

Miss La La

Another circus performer of Victorian Britain was the venerated Miss La La, born Anna Olga Albertina Brown, who was the subject of a series of art studies by painter Degas leading up to his 1879 Miss La La at the Cirque Fernando. Miss La La was an aerialist and vaunted performer of the European circus in the later 1800s, and was of mixed race. She performed solo and as part of Troupe Kaira, executing difficult aerial tricks while suspended from, or suspending others from, her teeth in iron jaw acts. One of her most famous tricks involved hanging upside down from a trapeze while holding a cannon suspended from a chain between her teeth, which was then fired at the conclusion of the act. A photograph of Miss La La in costume circa 1880 features a tightly fitted bodysuit and gathered shorts, with fringe detail accenting the high hip that is reflected in a v-shape at the bust. Stars are scattered at the neck and along the hipline, and her shoes are slippers tied with ribbons criss-crossing up her calves.

Although attitudes towards race differed between the US and Europe during this time, the exoticization of BIPOC performers such as Miss La La demonstrates how race and culture were viewed as commodities to exploit, rather than being perceived as smaller parts of the whole performer.

“Miss Lala’s ‘boyish physique’ and her racial distinction constituted fetishes that worked together to give the audience, mostly bourgeois, an experience of her as a curiosity, a grotesque circus performer, a sight and site of both terror and excitement. She represented the ultimate modern experience for her audiences”

Texts by Marilyn R. Brown (2007) and James Smalls (2003) examined Degas's painting of Miss La La in discussion of race, and each author focused on different topics within the perspective of Miss La La as featured subject. Smalls described the perception of Miss La La as “… ‘a modern amazon’ whose extreme exoticism – vested in her dark skin and muscularity – was both enticing and terrifying, alluring and repulsive” (Smalls, 2003, p. 370). It is this very muscularity and strength that allowed Miss La La to execute her incredible acts and entertain audiences across Europe. The description of her dark skin was echoed by Brown (2007) who discussed the difference in skin tone of Miss La La's legs between Degas's working sketches and the final painting, where Miss La La is depicted as wearing tights, indicated by wrinkles found behind her knee. What is unknown definitively is whether the change from a darker skin tone on her legs in the working sketches to lighter skin tone in the final painting is due to her tights being lighter in shade than her skin, or if Degas made a purposeful change to lighten her skin tone.

These two possible explanations are resonant in today's society, where the issue of lightening the skin of BIPOC performers, such as in images viewed on magazine covers or in beauty advertisements, and the lack of diversity in performance clothing basics such as dance tights and pointe shoes represent the continued practice of diminishing performers of color. Items such as tights, soft slippers, and bodystockings are widely used as foundational wardrobe pieces in artistic physical practices such as dance and circus arts, and serve both aesthetic and functional needs. Availability of these items in colors that match a wide variety of skin tones is essential so that performers need not spend precious time dyeing or coloring the items to match their skin tone, or even worse, to go without the protective layer altogether and risk potential injury such as abrasions to the skin.

Whereas racist and exploitative practices within the industry have denigrated and diminished the significance of Black circus performers, the historic examples of Miss La La and Ephraim Thompson are demonstrative of the importance of the inclusion of BIPOC circus artists in featured roles. The 2018 exhibition Circus! Show of Shows at the Museums Sheffield in the UK featured Miss La La at the Cirque Fernando on display, and elevated the performance aspect of the piece by teaming with circus performer Blaze Tarsha, who created a stunning aerial hoop act for the exhibition inspired by Degas's painting. Collaborations such as this celebrate the achievements of BIPOC performers who came before, as well as the circus artists of today.

Exoticism, Exploitation, and Cultural Appropriation in 21st Century Circus

Exoticism and exploitation in the circus is not a new topic of discussion, nor is it one that has yet fully been examined or resolved. However, especially due to the momentum of the Black Lives Matter movement in the summer of 2020, more and more members of the circus community are making these topics points of focus and exploration, as is evidenced by the results of a Google search of the terms “racism and circus”, which yields pages of links to circus schools and organizations across the US that have taken steps towards antiracist practices and added pages addressing such to their respective websites. In addition to a broader informed consciousness that not only acknowledges the existence of exploitation and racism in circus, it is essential to take steps towards more inclusive practices that work towards anti-racist policies and actions. This also means inclusivity for performers with disabilities or special needs. Circus artists with disabilities or special needs are equal participants in the culture and practices of circus, which is particularly evidenced by the work of social circus organizations, and companies such as Extraordinary Bodies, who provide a wonderful range of information and videos on their website about their performers and practices.

Circus artists with disabilities or special needs may have costuming considerations necessary for their mobility or equipment needs, and adaptive clothing practices should be incorporated into the costume design process from the start. Circus costume is not immune from exoticized, exploitative, or culturally appropriative practices and must be included in considerations and practices that work towards anti-racism and inclusivity. Listed below are some basic steps to add to this important conversation from the circus costume design perspective:

- Provide foundation basics (e.g. dance belts, tights, body tights, bras, binders) that not only match the performers' skin tone, but also encompass a range of sizes beyond the standard XS to XL.

- Consider accessibility in donning and doffing for performers who may have disabilities, difficulties with dexterity, or require accommodations for medical devices or equipment.

- Commit to eliminating culturally appropriative costume elements from circus productions.

- Meet the costume needs of the performer regardless of gender, size, age, ability, race, sexual orientation, or ethnicity.

The issues of exoticism and exploitation in the circus are important topics of discussion, and have been included here for the purposes of calling attention to the need for further study and action. Because these topics are each in their own right worthy of in-depth research and discussion, the curators have elected to highlight these issues here and have endeavored to create an exhibition that is inclusive and representative of the incredible circus community. Listed below are recommended resources on race and exploitation in circus, developed by and for the circus community:

- The American Circus Educators Association has compiled a range of texts, videos, and courses on their Race and Circus page.

- Founded by circus artist Veronica Blair, the Uncle Junior Project (UJP) celebrates and features the stories of Black circus performers through a variety of digital exhibitions, documentaries, and featurettes.

- Circus artist Noeli Acoba's YouTube series highlights racism in the circus and calls to action for the future of circus productions.

- Circus Talk's Wake Up Call for Inclusion series is a collection of panel discussions focusing on the stories and challenges faced by BIPOC circus artists.

- The John & Mable Ringling Museum of Art developed a Resource and Activity Guide for school groups that uses circus posters as references for discussion of Asian stereotypes.

Ring to Runway: Exoticism, Exploitation, and Cultural Appropriation

Exploitation

The Rick Owens Vicious Spring/Summer 2014 runway in Paris demonstrated an extraordinary departure from the typical fashion show. Featuring a stepping performance, the model-dancers wore garments designed to move. This runway performance is indicative of the fashion industry’s attempts to pivot away from the traditional ideals of what is or is not considered fashion, much in the way the garments worn by many contemporary circus artists are judged in what is or is not considered to be costume. By showing structured, minimalistic garments on people whose bodies are too often relegated as “other” in the fashion industry and denigrated rather than celebrated, Owens provided an example of the shift away from ‘conventional’ runway ideals and instead focused on clothing that can be worn by, and move with, any body.

However, it is important to note the outpouring of criticism that resulted due to stepping being used in a performative way that portrayed the predominantly Black model-dancer group as aggressive or angry, rather than helping to dispel stereotypes and misconceptions of the Black community’s place on the fashion runway. Stepping has a rich culture with an established history and is celebrated in events in the US and beyond, but by using these model-dancers in a performative rather than celebratory way, Owens upheld the conventions of the industry wherein people whose bodies are “othered” by fashion do not carry the same impressions or place on the runway.

Cultural Appropriation

From model Karlie Kloss in a Native American war bonnet for Victoria's Secret, to dreadlock wigs on white models and the use of turbans as fashion accessory, the practice of cultural appropriation is common on the fashion runway. This problematic practice upholds the view that symbols and dress elements from non-Western cultures can be co-opted and worn as decoration, regardless of their true histories and meanings. Designers who use cultural appropriation are exoticizing elements that are removed from their context and placed on other people as decoration, much in the way items of non-white cultures have been exoticized and used as circus costume.

For source information, please see the References page under the Final Bows tab.