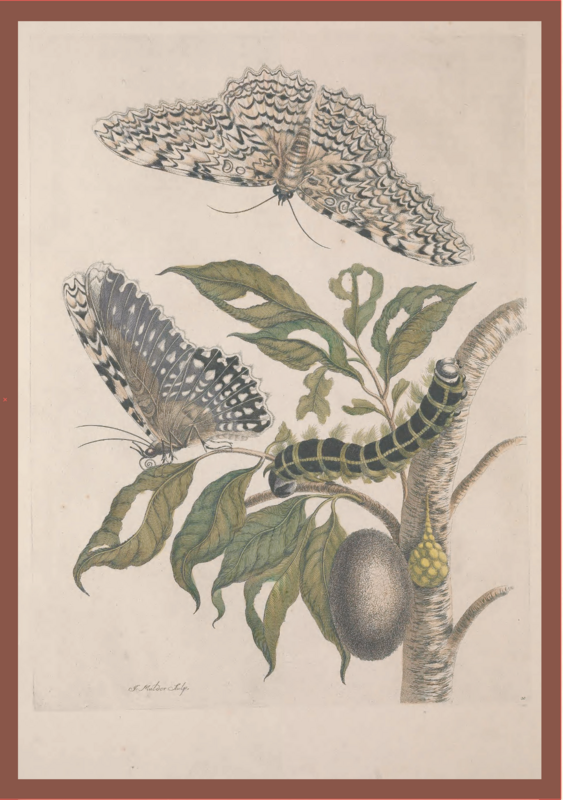

Metamorphosis Insectorum Surinamensium

Maria Sibylla Merian

Maria Sibylla Merian (1647-1717) was an influential naturalist and artist of the late 17th century who gained fame in her own lifetime for her remarkable studies of insects. Her book Metamorphosis Insectorum Surinamensium, singled out by Vladimir Nabokov for its "lovely plates of Surinam insects," is considered a masterpiece of scientific illustration. For a precocious young butterfly collector growing up in early 20th century Russia, Merian’s illustrations of South American wildlife would have provided a colorful glimpse into a faraway land along with an irresistible invitation to imagine fascinating worlds in butterfly discovery ahead.

Enlightened education

Merian grew up in a family of engravers in the city-state of Frankfurt, a prosperous European center of trade and economic activity, where she had immediate access to extensive collections of fine art as well as formal lessons in watercolor, painting, engraving and in the more traditionally woman's art of embroidery. Fruitfully—and given her gender quite remarkably—encouraged by her family to cultivate her creative talents, she became a master painter and engraver and a respected teacher of drawing and painting. Naturally inquisitive and ambitious, she was also moved by the ideas of the Scientific Revolution and the unfolding Age of Enlightenment to which she was exposed in her upbringing—in particular the value placed upon taking an empirical approach to understanding life. Her devotion to close, almost immersive observation of the organisms found in the teeming, colorful world of nature focused her artistic talents on the creation of brilliant botanical and entomological illustrations.

Caterpillar studies

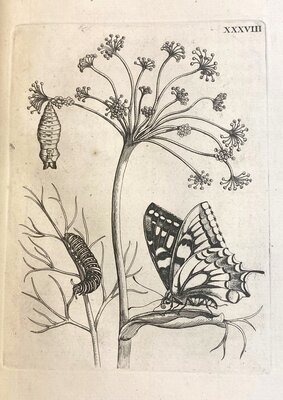

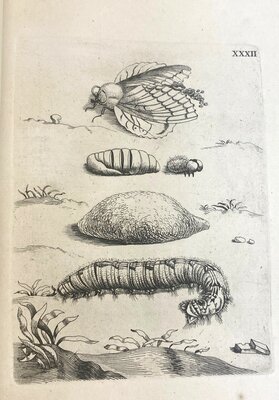

Merian first gained fame for her finely detailed engravings of flowers painted from life, which found particular appreciation among fellow artists and embroiderers who sourced from her work intricate patterns and models useful for their own creations. But she also found deep inspiration in another, perhaps rather less likely subject—caterpillars. These she encountered easily while exploring the silkworm factories of Frankfurt's thriving textile industry as a child and while combing through the gardens, field and forests in and around the different cities of her adult life. Mesmerizing to the artist’s eyes in the diversity of their form, color and pattern, caterpillars also drew her attention because of the astonishing changes they underwent as she observed her carefully collected live specimens at home.

Merian’s first insect publication, Der Raupen Wunderbare Verwandelung Und Sonderbare Blumennahrung, a two-volume set depicting the life cycles of butterflies and moths, published in folio format between 1679 and 1683 (and again posthumously in Dutch under the title De Europische Insecten: Naauwkeurig Onderzogt, Na't Leven Geschildert) was a major work that drew attention quickly. By recognizing and depicting in meticulous detail the exact forms characterizing the different life phases of the various caterpillars covered, from egg to larva then pupa and finally to butterfly or moth—a novel approach to insect drawing in the late 17th century—Merian made an important contribution to the era’s understanding of insect life, in particular helping to lay to final rest any lingering notions of angiogenesis—the prevailing idea among earlier naturalists that insects emerged fully formed from rotting organic material. Her illustrations not only presented stunningly beautiful artwork but in important ways helped solidify the foundations of modern biology.

Science, art, and Suriname

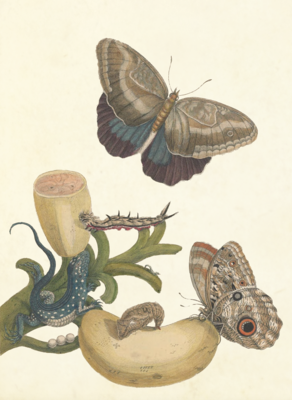

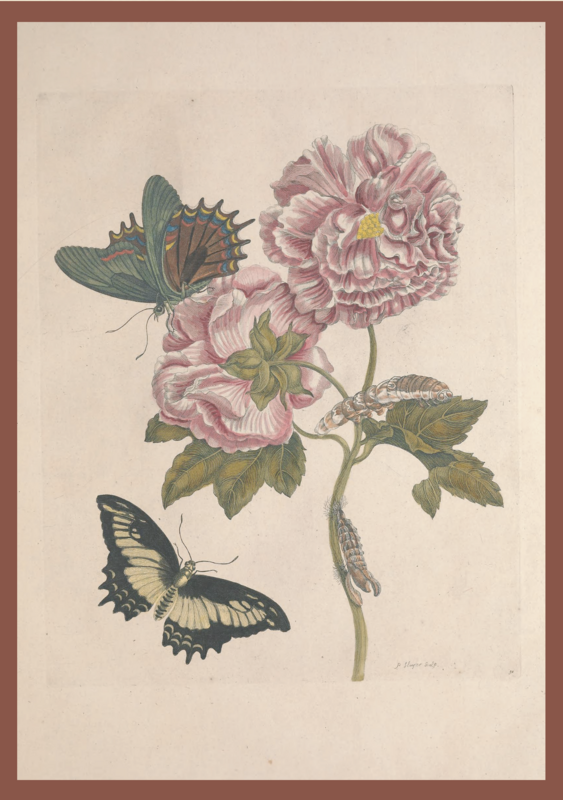

By the time Merian was in her mid-40's she had moved to Amsterdam with her two daughters. There, encounters with exotic specimen collections—feverishly gathered from all over the world by the wealthy collectors of that mighty center of Europe's expanding global networks of trade and colonization—only deepened her focus on insect study further. While these flashy collections were highly prized, Merian knew they were leaving a major part of the insect story out. From her own work she knew each of the exotic creatures featured in a given case would have been sustained by distinctive relationships to specific plants and undergone fascinating transformations—relationships and processes that were simply not evident in the now lifeless specimens.

Resolved to address this gap, in 1699 Merian undertook a self-funded two-year field trip to the Dutch colony of Suriname, accompanied by her 20-year-old daughter and assistant Dorothea. The journey itself was noteworthy, as it was rare for any European outside the sugar trade to visit Suriname, and even more so for two women traveling by themselves. As she settled into studying, drawing, and preserving insects and the plants they favored, as found in the forests and Dutch plantations around the colonial town of Paramibo, Merian’s devotion to her project was considered strange by the Dutch colonists, whose focus was almost exclusively on sugar cultivation.

For the scientific community, however, the 2-volume work that came of Merian's ambitious undertaking was a crowning achievement. Featuring sixty engraved plates of Merian’s illustrations along with her observations and commentary, Metamorphosis Insectorum Surinamensium was a pioneering study on the natural history of Suriname. Once again, her style of depicting insects in their natural habitats rather than drawing them in isolation on a blank background presented a path-breaking approach to depicting insects, reflecting an early acknowledgment of the importance of ecological relationships in the insect world that would influence the practice of scientific illustration for decades if not centuries to come.

It is also true that more than any other scientific illustrator of her day, the impact of Merian’s aesthetically breathtaking artwork—famously rich in hue, dynamic in composition, vibrant in presentation—extended well beyond practitioners of science illustration to influence traditions of flower and plant depictions in the European art of the following centuries. In the copy of Merian's Metamorphosis that the Nabokovs were fortunate to have as part of their private library, the family's aspiring young lepidopterist encountered what can only be considered a true fusion of art and science.

The Special Collections of Mann Library at Cornell hold the 1730 edition of Maria Sibylla Merian's De Europische Insecten: Naauwkeurig Onderzogt, Na't Leven Geschildert (Amsterdam). Full-color digitized copies of both the original German language version of this work as well as Merian's later work on the insects of Suriname may be browsed online at the Biodiversity Heritage Library: Der Raupen Wunderbare Verwandelung Und Sonderbare Blumennahrung (Nurnberg, Germany , 1679 - 1683) and Metamorphosis Insectorum Surinamensium (Amsterdam, 1705).