Winogradsky Rothko

steel, glass, pond water, mud

32 3/4" x 56" x 2 1/2"

Ithaca, NY

2004

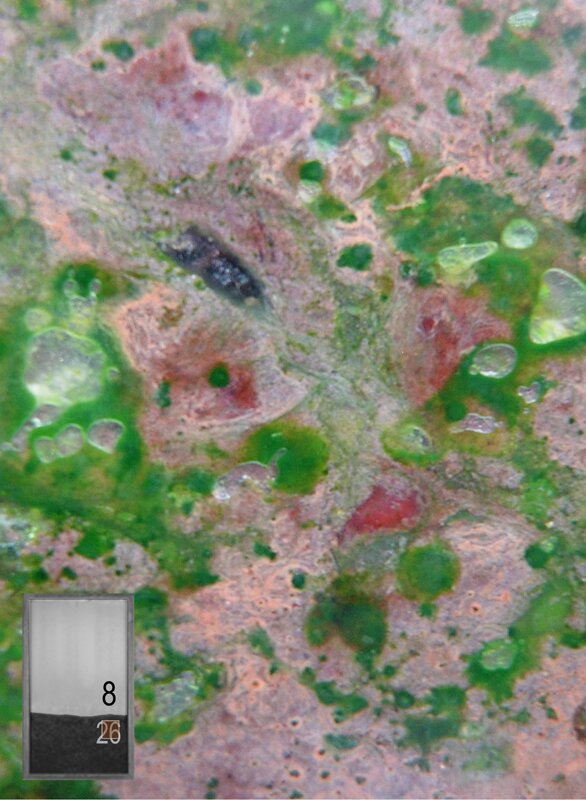

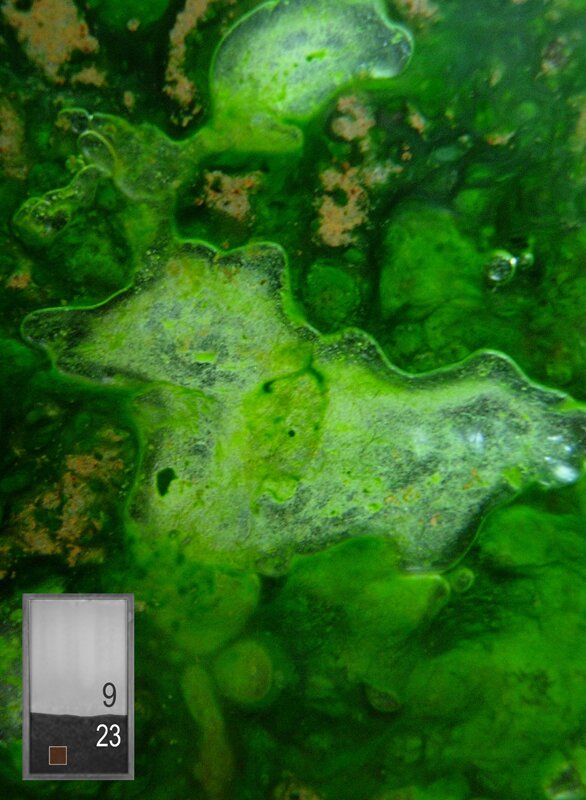

Installed outside between Mann and Emerson on the Cornell campus, a steel and glass frame – made in the dimensions of Mark Rothko’s Untitled, 1949 – was filled with local mud and water from Beebe Lake. By applying a microbiological identification technique developed by a 19th century soil scientist, Sergei Winogradsky, pigmented bacteria existing in the mud and water composed the palette. Though difficult to see individually, microorganisms capable of producing pigments through photosynthesis are found in all kinds of soils. Light intensity, access to nutrients, and oxygen levels all define which position in the soil column a given bacterium will be able to grow. As these bacteria colonize their optimal zones, they change their environments by depleting their resources and releasing by-products. As a given species reaches its carrying capacity, the no longer hospitable environment to the original colonizer may now be the optimal environment for a potential predecessor to that zone. Exposing the cross-section of soil to sunlight, traditionally unseen organisms become indicators of the complex biochemical succession of a soil landscape thus creating an evolving color-field of living pigments.

How science and art came together

I learned about the Winogradsky Column one summer when I was a marine biology teaching assistant. On a field trip, the students and I filled clear two-liter pop bottles with mud from a freshwater/seawater mudflat on the coast of New Hampshire, USA. We brought the mud back to our wetlab, stirred in a bunch of eggs, grated some blackboard chalk, shredded some Union Leader newspapers, and covered the slurry with plastic wrap. We watched our own version of the Winogradsky Column for six weeks of the summer program. Little horizontal bands of color appeared and disappeared.

Somewhere along the way, I remembered as a child, taking a field trip to the Hood Museum in Hanover, NH, USA where I saw my first Mark Rothko painting, Orange and Lilac over Ivory (1953). I remember thinking it looked like a big open window, the kind you see in summer, warm and cool.

For me, the abstract Rothko pattern – translucent layering of horizontal color – is everywhere in the world. For example, gravity sets up a vertical armature that layers ecosystems. Without the energy that animates life, everything succumbs to the pull of gravity. The dust settles, the tree falls and materials line up in horizontal bands. In the case of soil, layers of chemistry across a soil landscape provide a variety of homes for diverse bacteria. These niches are suitable to various bacteria at various times as the natural resources undergo infinite structural changes by biologic activity.

To read further, try

Winogradsky Rothko: Bacterial Ecosystem as Pastoral Landscape

Journal of Visual Culture. 2008; 7(3):309-334. doi:10.1177/1470412908096339

Made in the dimensions of a Mark Rothko painting, a steel and glass frame was filled with mud and water. By applying a microbiology technique developed by a 19th-century soil scientist, Sergei Winogradsky, pigmented bacteria that existed in the mud and water composed a landscape. As bacteria colonize their optimal zones, they change their environments by depleting their resources and releasing by-products. As a bacterial species reaches its carrying capacity, the environment no longer hospitable to the original colonizer may now be the optimal environment for a potential successor to that zone resulting in an evolving color-field of living pigments. The appearance/disappearance of color indicates both procurement and loss of finite material resources; the agents that act out upon the landscape and synthesize change become acted upon by their consequentially changed world. For this article, the ecological industry of the figure and field of Winogradsky Rothko serves as a point of departure for thinking toward a notion of ecological rationality.

Acknowledgements

Steve DeGloria and Susan McCouch who each ratcheted up support for this installation. Cornell Council for the Art and the Cornell College of Agriculture and Life Sciences for financial support.

Tom Besemer for excellent craftsmanship. My Janes and Johns that kept me steady through the first version and onto the second. And Buzz Spector for helping me to the see the way.

In the Press

- Art and Science, Ithaca Journal, September, 2004

- Decomposition - hope for the future, 2017

- Building Sustainability with the Arts, edited by David Curtis, 2017

- Metaphors for Abstract Concepts by Lyndon Stone

- The Aesthetic Microbe - ProkaryArt and EukaryArt by Simon Park, 2007

- Tristes Entropique: steel, ships and time images for late modernity, by Mike Crang