Fun and Profit: The Children’s Literature Industry

In the late 1990s a series of books about a certain boy wizard appeared on the scene, and the business of publishing children’s books has never been the same. Fans lined up outside stores for the next book’s release. And not just young fans: suddenly it was cool for adults to read books written for children and teens, too. Film adaptations, toys, costumes, and other collectibles helped fuel the fire and gave the kid lit industry a surge in profits. Now, while publishing of other print media is dwindling, revenue from children’s books has seen a 12% increase in the past year. New series are constantly appearing, celebrities and well-known adult authors are penning their own books for kids, and grown-ups represent about half of the readership for teen literature. But like any business, children’s book publishing has always been profit-driven, churning out products – ahem, literature – to entice young consumers – um, readers.

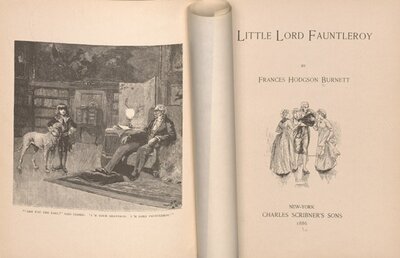

Frances Hodgson Burnett. Little Lord Fauntleroy. Illustrations from drawings by Reginald B. Birch. New-York: Scribner, 1886.

Burnett’s first novel, about a poor young American boy who charms his way into his crusty English grandfather’s heart (and fortune), was extremely popular in its day, and has endured several film adaptations over the past century. But the book is most notable for launching a fashion fad that humiliated an entire generation of little boys. Burnett based the Little Lord’s appearance on her own sons, whom she dressed rather fancifully in Restoration-esque velvet suits with short pants and huge lace collars, and kept their hair in long ringlets and bangs. Using Birch’s illustrations as a model, American mothers embraced the entire aesthetic, costuming their miserable boys in Fauntleroy suits and “love locks” well into the 1910s.

Victor Appleton. Tom Swift and His Motor Boat. Tom Swift Series #2. New York: Grosset & Dunlap, [c1910].

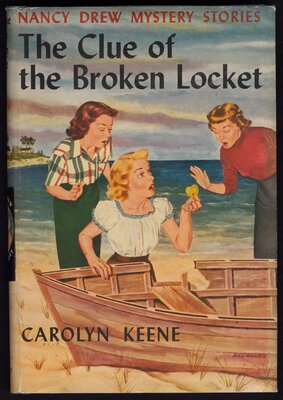

Carolyn Keene. The Clue of the Broken Locket. Nancy Drew Mystery Stories #11. New York: Grosset & Dunlap, c1934 [imprint ca. 1950].

Franklin W. Dixon. The Missing Chums. Hardy Boys Mystery Stories #4. Illustrated by Walter S. Rogers. New York: Grosset & Dunlap, ca. 1923.

What do Tom Swift, Nancy Drew, the Hardy Boys, the Bobbsey Twins, and the Happy Hollisters all have in common? Besides being successful children’s mystery series, that is? They are all products of the Stratemeyer Syndicate, a book-packaging company established in 1905 that produced an enormous number of children’s books while operating in complete secrecy until the 1970s. Edward Stratemeyer was a freelance writer who decided to apply the business model of the story periodicals – an editor providing an outline and hiring a ghostwriter to finish the story – to the kid lit industry. He kept a stable of authors who wrote under the pseudonyms he created for each series, and were contractually forbidden to reveal their connection with the books.

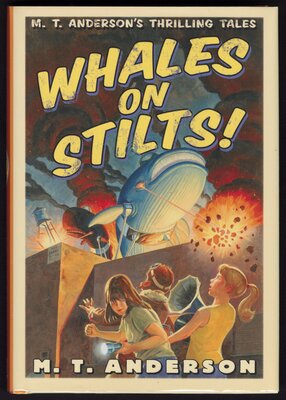

M.T. Anderson. Whales on Stilts. Orlando: Harcourt Children’s Books/Harcourt, Inc., ca. 2005.

Poor Lily Gefelty feels boring and ordinary compared to her friends: Jasper Dash, Boy Technonaut, bears a striking resemblance to Tom Swift with his steampunk-ish inventions; and pretty, Buffy-esque Katie Mulligan is always having to fight off the supernatural creatures that regularly invade her neighborhood. They each have a book series based on them, too – but Jasper’s has been out of print for a while. Anderson’s “Pals in Peril” series is a post-modern homage to the tradition of formula fiction for children, from the Stratemeyer Syndicate to Goosebumps.

J. K. Rowling. Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone. New York: A.A. Levine Books, 1998.

The Boy Who Lived, and the Book That Blew Up. But why? Why did this book become so popular, so beloved, that it completely changed the rules of the game? Some critics claim that Rowling’s first novel is not “great literature,” that it’s derivative and full of clichés. But it’s a prime example of the “hero’s journey” motif, which has shaped many of the most successfully enduring stories, from King Arthur to Star Wars. And Harry is a perfect hero: an orphan underdog, mistreated by his guardians, who discovers he is not only special among humans in his ability to do magic; he is special among wizards, a humble hero who doesn’t even remember his victory over the ultimate villain… kind of a Fairy Tale/Orphan/Hero’s Journey triple-whammy. How could he not succeed?

Harry Potter Collectibles: Collector Handbook and Price Guide. Middletown, CT: CheckerBee Pub., 2000.

The Potter phenomenon spawned a highly successful film franchise, costumes, action figures, Lego sets, spin-off books, a theme park… and just about anything else that might possibly make J.K. Rowling, Scholastic and Warner Bros. a little bit richer.

Suzanne Collins. The Hunger Games. New York: Scholastic Press, 2008.

Since about 2000, a few book series have been called “the next Harry Potter,” generally in reference to commercial success rather than content. The Twilight books (a romance/horror series about a girl in love with a vampire, and sometimes maybe a werewolf too) and the Hunger Games series (a trilogy about a girl forced to compete in post-apocalyptic gladiator games, and the two boys who love her) have nothing to do with wizards, witches or boarding schools. But their rabid fans, crossover appeal between teens and adults, and big-budget film adaptations have secured the Harry Potter label for both series.