Introduction

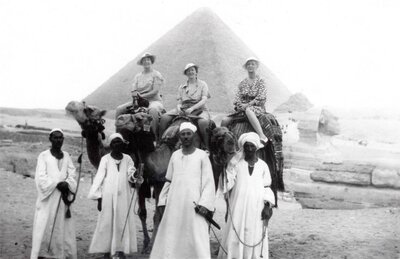

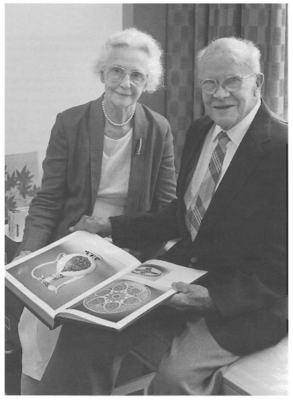

In this digital fashion exhibition, we examine the collecting practices of Professor Beulah Blackmore and Mrs. Ruth Sharp who contributed to the development of two ethnological dress collections on Cornell’s campus. Blackmore taught courses within the areas of clothing and textile design at Cornell from 1915 to 1951, while Sharp contributed to anthropological projects at Cornell as the wife of Lauriston Sharp, Cornell’s first Anthropology faculty member, hired in 1936, and the founder of the university’s Southeast Asian Program. Blackmore and Sharp donated collections of ethnological dress to the Cornell Fashion + Textile Collection and the Department of Anthropology Collections in the early to mid-twentieth century. Readings of university dress collections in the United States tend to emphasize the vast number of garments held within these collections that were manufactured and sold by leading department stores or couture houses. However, Blackmore and Sharp secured funds to travel abroad and, as a result, collected examples of dress throughout Southeast Asia. They also collaborated with other faculty, staff, and students affiliated with Cornell to collect additional dress- and textile-related artifacts from around the world. Blackmore and Sharp’s collecting practices disprove the assumption that university dress collections primarily consist of Euro-American fashion. Instead, both of these women were interested in diversifying Cornell’s curriculum and provided students with primary materials for them to learn about the cultural practices of Indigenous communities and peoples. However, as white women interacting with and collecting from Indigenous communities abroad, both Sharp and Blackmore’s actions are situated within systems of colonialism, imperialism, and U.S. intervention. Therefore, we chose to engage in an “ethnography of collecting” and critically examine how these women’s understandings of Indigeneity are documented and produced through their collecting practices, as well as how issues of disciplinary boundaries and collectors’ identities produce specific forms of collections within university spaces. These issues are explored throughout the exhibition in four thematic sections: More than “Women’s Work:” Two Dress Collections on Cornell’s Campus, Collecting Souvenirs: Tourist Art in the University Collection, Filling in the Gaps: Missionaries in Service of the University Collection, and Animating Costumes from Many Lands: Circulating Dress on Cornell's Campus.

Redressing the Binary

The title of this exhibition is drawn from the fashion showcase “Costumes from Many Lands,” that was organized by Blackmore in 1938 and 1939 for Farm and Home Week, an event held every February on Cornell’s campus from 1915 to 1954. According to the press release, the showcase was supposed to promote world peace by providing the audience with a greater understanding of the traditions and customs of other peoples. By highlighting the “authentic” or “traditional” costumes of over twenty-seven countries, Blackmore however perpetuated the very divisions she sought to disrupt. Historically, the term “costume” has been used by fashion historians to refer to those styles worn by members of a particular ethnic group. Compared to Euro-American fashion that was viewed as innovative, dynamic, and aesthetic, ethnic dress was believed to be unchanging, authentic, and symbolic. This particular terminology therefore aligned with the colonial project that sought to differentiate the West from the rest of the world. By organizing their collections along these lines, Sharp and Blackmore’s collecting practices, at times, relied on oppositional and essentialist thinking that compartmentalized the world into different geographical regions and thereby reaffirmed a Eurocentric view of the world. We also chose to reference the showcase in our exhibition title because it speaks to the modes of engagement, collecting, interpretation, and dissemination that both Blackmore and Sharp pursued and because it highlights the exploratory nature of both of their projects, as well as our own inquiry in documenting and contextualizing the histories of these collections.

In recent years, museum professionals have begun to reconfigure and reframe ethnological collections of dress in order to move beyond the assumption that certain styles are only associated with a specific geographical location. Shifting from one cultural frame of reference to another however poses several challenges for those who engage with collections that were meant to organize the world, people, and objects into different categories. As a result, we encountered numerous obstacles while curating this digital fashion exhibition. Compared to the extensive documentation of Blackmore’s collecting practices, we were unable to obtain detailed records of Sharp’s collection, as well as photographs of her in the field. This is perhaps emblematic of what information the field of Anthropology thought to be of value as well as the limited opportunities that were available to women in Cornell’s Department of Anthropology at the time. The same may also be said for the spaces both of these women had access to abroad. As a tourist, Blackmore oftentimes purchased items that were created specifically for the tourist market, while Ruth chose to collect clothing, textiles, and ceramics adjacent to her husband’s work in Thailand. As a white woman, Ruth was not able to visit certain spaces within the field and her movements were restricted to Mae Chan, Thailand where the project team was based. We also encountered issues when photographing artifacts for the website. In order to avoid framing these objects in relation to that of the Western or Indigenous body, we decided to photograph all of the clothing and textiles flat and allow for the garments to be embodied by visual representations of Indigenous peoples, Christian missionaries, or Cornell students who are shown wearing the garments in photographs and postcards. Lastly, in an effort to provide visitors with additional information on the garments collected by Blackmore and Sharp, we have included hyperlinks to online resources that provide visitors with additional information beyond that in which Blackmore and Sharp collected in the field. Since we primarily focused on the collecting practices of these women, these resources serve to highlight the production and consumption of Indigenous dress practices in a transnational context and thereby demonstrate how they are not static nor fixed, but constantly evolving.

Sources:

Lillethun, A., Welters, L., & Eicher, J. B. (2012). (Re)Defining fashion. Dress, 38(1), 75-97.

Marcketti, S. B., Fitzpatrick, J. E., Keist, C. N., & Kadolph, S. J. (2011). University historic clothing museums and collections: Practices and strategies. Clothing and Textiles Research Journal, 29(3), 248–62.

McMurry, E. F. (1975). The Cornell costume collection: Its nature, uses, and needs. New York State College of Human Ecology.

O'Hanlon, M., & Welsch, R. L. (Eds.). (2001). Hunting the gatherers: Ethnographic collectors, agents, and agency in Melanesia 1870s-1930s (Vol. 6). Berghahn Books.

Press release for “Costumes of Many Lands,” February 14, 1938. Documentation and Review of Ethnic Collection, Folder 29, Box 11, Cornell University Department of Textiles and Apparel Records #23-19-2807, Cornell Rare and Manuscript Collection, Ithaca, New York.

Taylor, L. (2004). Establishing dress history. Manchester, UK: Manchester University Press.