Animating Costumes from Many Lands: Circulating Dress on Cornell's Campus

Introduction

Based on their particular interests and occupations, Blackmore and Sharp chose to circulate their dress collections differently once they returned to Cornell’s campus. The ways in which they represented their collections within departmental curriculum, publications, and exhibitions however led them to serve as repositories for the “authentic costumes” of Indigenous peoples. According to James Clifford, authenticity is created once an object is removed from its initial integration within everyday life and placed in a different frame of reference. The same may be said for the ways in which dress- and textile-related artifacts are divorced from the body once they enter the museum or university collection. While we can easily determine how a garment was made as well as what techniques or materials were used in its production, it is much harder to understand how it was worn or used by the original wearer. As a result, Blackmore and Sharp explored different strategies for animating their dress collections in order to indicate how such ensembles were worn by the Indigenous communities they engaged with abroad. For example, Sharp highlighted Yao self-fashioning and the production of cultural items in university publications, while Blackmore developed the fashion showcase “Costume of Many Lands” as a means of illustrating how these garments were worn on the living body. While Sharp and Blackmore intended to highlight the diverse practices of Indigneous crafts peoples, the ways in which they chose to frame their collections, at times, reinforced a Eurocentric view of the world.

Beulah Blackmore

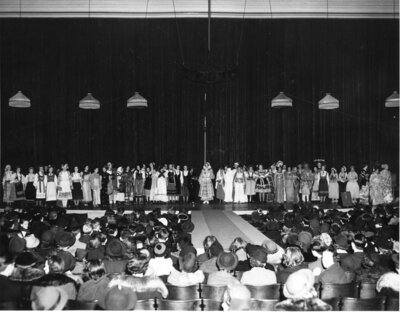

Blackmore chose to circulate her collection in the fashion showcase “Costumes of Many Lands” during Farm and Home Week, an event organized by the New York State College of Agriculture every February from 1915 to 1954. This however was not the first public display whereby live models were seen wearing ethnological clothing and textiles on Cornell’s campus. In 1919, several students studying agriculture and home economics at Cornell participated in the “Exhibit of Foreign Costumes” that also took place during Farm and Home Week. Images of the event showcase students wearing “authentic costumes” from Hungary, Scotland, Mexico and Norway. In fact, this desire to display dress artifacts on live models was a common practice throughout the first half of the twentieth century. According to Ingrid Mida, museums would organize runway presentations of their dress collections in order to show how the garments were worn by the original wearer. In doing so, they attempted to recreate the original context or setting in which these garments would have been worn. Blackmore’s desire to provide the audience with an “authentic” representation of the ensembles she collected led her to work with several international students in the College of Home Economics including Lathlia Kumarappa ‘39, a transfer student from Mumbai, India who helped Blackmore dress students for the 1938 showcase.

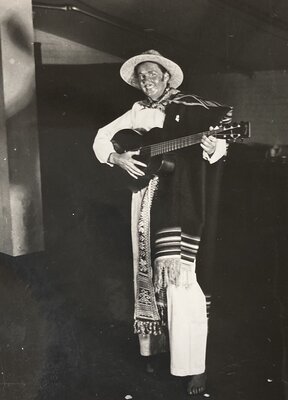

Even though Blackmore sought to portray an accurate representation of Indigenous dress practices, her desire to recreate the original context in which these garments were worn led her to paint the faces of several white-appearing students who dressed up and performed as the “Other.” To the left we see Jean Pettit ‘39 holding a guitar while wearing what appears to be a man’s white mariachi suit in brownface. The practice of dressing up in black or brownface became popular in the nineteenth century and drew heavily upon racial stereotypes that characterized black and brown peoples as lazy, ignorant, cowardly or hypersexual. The problematic nature of Blackmore’s display practices that involved white female students playing “dress up" in the clothing and fashions of identities not their own thus clashed with her intention to educate others about the dress practices of diverse peoples.

Ruth Sharp

Until her collection of clothing and textiles was donated in 1995, Sharp’s collection was likely only circulated through the texts she wrote about Indigenous dress practices and tourist economies, which were published in reports on the Bennington-Cornell Survey of the Hill Tribes of Northern Thailand. Therefore, material related to her collection was circulated discursively through textual practices. The two essays that she wrote about the textiles of the tribal communities living in Northern Thailand were a report appendix promoting the creation of a centralized tourist economy to financially support Indigenous artists and contribute to the continuation of cultural practices as well as a chapter on Yao (Mien) dress practices entitled “It’s Expensive to be a Yao.” The language she uses in the piece on Mien clothing is evocative and uses active language to portray a narrative, compared to the other more standard anthropological documentation texts in the report, it reads as an engaging and accessible text. However, in general, she describes Yao individuals in generalizing terms, which reduces them only to their status or role, and presents their culture as homogenous, with little dynamic adaptation and people as interchangeable . Her writing also characterizes the Yao as subjects who are easily identifiable and knowable by anthropologists, not as active agents with their own complex intentions.

Clothing and Textiles

Sources

Clifford, J. (1988). The predicament of culture: Twentieth-century ethnography, literature, and art. Harvard University Press.

Entwistle, J. (2000). The fashioned body: Fashion dress and modern social theory. Polity Press.

Mida, I. (2015). Animating the body in museum exhibitions of fashion and dress. Dress, 41(1), 37–51.

Press release for “Costumes of Many Lands,” February 14, 1938. Documentation and Review of Ethnic Collection, Folder 29, Box 11, Cornell University Department of Textiles and Apparel Records #23-19-2807, Cornell Rare and Manuscript Collection, Ithaca, New York.