Collecting Souvenirs: Tourist Art in the University Collection

Introduction

Both Sharp and Blackmore interacted with souvenir and tourist markets while abroad. In their work on commoditized arts and cross-cultural encounters, Ruth Phillips and Christopher Steiner write about how Indigenous makers respond to and engage in commodity markets both for economic needs and to assert self-identification in spaces of colonial hegemony. Like other textiles, these objects produced for sale in cash economies challenged the art/artifact dichotomy that the formations of natural history and art museums constructed. While souvenir arts were purchased by Victorian travelers at the same time as many museum collections were founded in the West, these pieces were often ignored by collectors or obscured in collecting records to preserve Western ideas of Indigenous authenticity. These souvenir art forms challenged notions of authenticity as they were often understood as “hybrid” arts due to the artists’ willingness to dynamically modify styles to meet the demands of their markets. Additionally, the idea of items created for sale conflicted with notions of authenticity that valued older objects which had been used for long durations by communities, especially if they were from periods when there were less colonial interventions in those communities. To counteract notions of inauthenticity, tourist spaces have also adapted. Dean MacCannell has written about “staged authenticity,” which includes not only the production of authenticity in outward audience facing spaces, but also the constructed illusion of entry into back stage spaces for tourists to confirm authenticity. Blackmore and Sharp’s experiences in relation to souvenir markets also highlight both the construction of tourist economies and the consumption of material made for tourists. Sharp wrote a piece promoting the sale of textiles in tourist markets to support economic development in Northern Thailand and Blackmore’s interest in “traditional” dress practices led her to purchase items that were produced for and worn by tourists.

Beulah Blackmore

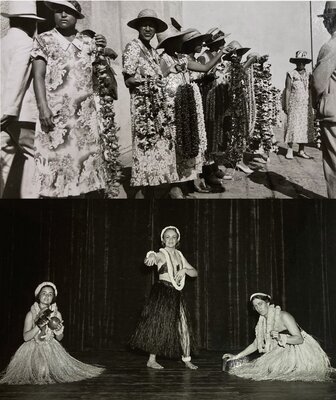

In January of 1936, Blackmore set out on a trip around the world with her colleague, Marion Pfund. Together, they crossed the Panama Canal and traveled throughout Asia, the Middle East, Northern Africa and Eastern and Northern Europe. Blackmore returned to Cornell with over twenty complete ensembles not including flat textiles and accessories. An examination of the garments she collected for the department reveal a great deal about the spaces in which she and Pfund visited abroad as well as the different dress practices she sought to document. In Hawai’i, Blackmore chose to purchase two grass skirts, anklets, and leis rather than a mumu worn by the women who sold leis to her and Pfund at the Pier in Honolulu. The donning and doffing of grass skirts and anklets during hula performances in the 1930s led these articles of clothing to become a popular icon of Hawai’ian culture in the United States and is perhaps the reason Blackmore chose to purchase these items even though the Indigneous peoples of Hawai’i wore skirts made out of kapa (barkcloth).

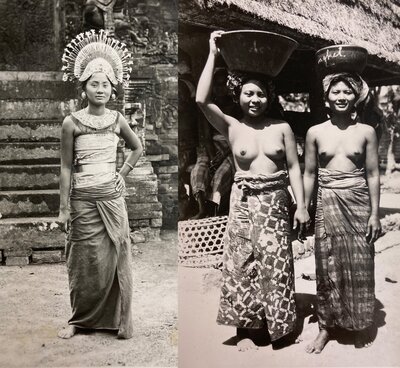

Blackmore also visited several tourist attractions throughout Indonesia that provided a space for her and Pfund to engage in “shared authenticity.” In Bali, Blackmore purchased a dance ensemble after witnessing the performance of several Balinese dances that confirmed the “authenticity” of the ensemble she chose to collect. The design of the dance ensemble Blackmore purchased however did not align with the everyday dress practices of Balinese women who often wore minimal clothing only on the lower half of their body. In addition to purchasing clothing and textiles worn by and for tourists, Blackmore collected hundreds of postcards that were later used to inform how students and missionaries wore the twenty ensembles Blackmore collected for the 1938 and 1939 fashion showcase, “Costumes of Many Lands,” including the ensemble she obtained in Jaipur, India that was worn by Dhimatria Tassi ‘39, a junior in Home Economics at Cornell. Blackmore’s reliance on tourist markets raises concern for the types of cultural expression represented within Cornell’s Fashion + Textile Collection. In an effort to document Indigenous dress practices before Western acculturation, Blackmore collected clothing and textiles that, at times, reaffirmed Western constructed narratives of Indigenous authenticity.

Ruth Sharp

The aim of the Cornell Thailand Program was to aid in the assimilation of the hill tribes of Northern Thailand into the Thai state. In the publication A Report on Tribal Peoples in Chiengrai Province North of the Mae Kok River, Ruth Sharp authored an appendix arguing for the development of arts and crafts markets in order to support the maintenance of tribal material cultures, which she believed were in threat of “extinction” due to changing practices and increased contact with outsiders. She argued that if these practices were to cease, the tribal individuals and communities would become demoralized and anonymized. Therefore, through this proposal, it is evident that although advocating for assimilation, Sharp and the other project members believed that cultural groups should maintain aspects of their own identity, as Sharp wrote, to “help ease the orderly integration of hill tribes into the Thai national economy, polity, and society as ethnic minorities retaining their self-respect, dignity, and group morale." The conclusions of the full report indicate that the project team believed that incorporating the tribal groups into cash economies would allow them to become more integrated into the Thai population since they would have money to spend outside of their villages. In the appendix, Sharp proposes methods to create tourist markets by selling handicrafts in Bangkok, as she did not believe local tourist economies could create enough demand to guarantee the need for regularly produced high quality items. This mode of tourist production is referred to as indirect tourism, as it is sponsored through intermediaries and there is no direct contact between the tourists purchasing the items and those making them. Indirect tourism would therefore not require the same performative aspects of direct tourism on the part of the Indigenous makers, although there were likely performative techniques employed in the markets where items were sold.

Clothing and Textiles

Sources

Andrews, H., Jimura, T., & Dixon, L. (Eds.). (2019). Tourism ethnographies: ethics, methods, application and reflexivity. Abingdon, Oxon: Routledge.

Arthur L. B. (2000). Aloha attire: Hawaiian dress in the twentieth century. Atglen, PA: Schiffer Books.

Letters of Beulah Blackmore and Marion Pfund on their trip around the world in 1936. Box 47, New York State College of Home Economics Records #23-2-749, Cornell Rare and Manuscript Collection, Ithaca, New York.

MacCannell, D. (1989). The tourist: A new theory of the leisure class. Revised edition. New York: Schocken Books.

Phillips, R. B., & Steiner, C. B. (1999). Art, authenticity, and the baggage of cultural encounter. In R. B. Phillips and C. B. Steiner (Eds.), Unpacking culture: Art and commodity in colonial and postcolonial worlds (pp. 3-19). Berkeley: University of California Press.

Sharp, R.B. (1964). Appendix I: Tribal arts and crafts. In L.M. Hanks (Ed.), A report on tribal peoples in Chiengrai Province north of the Mae Kok River (pp. 83-102). Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University, Dept. of Anthropology.