Olive Whitman Memorial Scholarship Fund, 1929-1942

The education of Hodinǫ̱hsǫ́:nih (Haudenosaunee) women at Cornell continued into the 1930’s and ’40s. In 1927, Dr. Bates worked with the lineage organization, Daughters of the American Revolution, of which Van Rensselaer was a part of, to create a scholarship program for Hodinǫ̱hsǫ́:nih women within the newly formed New York State College of Home Economics. The Olive Whitman Memorial Scholarship Fund, named after the late wife of then New York Governor, Charles Whitman, supported five Hodinǫ̱hsǫ́:nih women who enrolled in the College as full-time students between 1929 and 1942: Beulah Brayley (Skarù·rę’) (Tuscarora), Inez Blackchief (Onöndowa’ga:’, Deer Clan), Bessie Theresa Ransom (Kanien’kehá:ka) (Mohawk), Henrietta Hoag (Onöndowa’ga:’, Beaver Clan), and Constance Tahamont (Onöndowa’ga:’, Turtle Clan). Despite Van Rensselaer’s efforts to support Hodinǫ̱hsǫ́:nih women at Cornell, only one recipient, Henrietta Hoag, graduated with her four-year degree. This was largely due to the lack of support these women received from the D.A.R. as well as Cornell faculty and staff.

Olive Whiteman Scholarship Committee

The D.A.R. greatly influenced who the funds were distributed to and how. They were only interested in funding Hodinǫ̱hsǫ́:nih women who enrolled in the College as full-time students. In addition, some of the organization’s members felt it would be better to offer a general fund that would allow Hodinǫ̱hsǫ́:nih women to attend any college in New York state. For these reasons, the $10,000 Dr. Bates raised was managed and distributed by the D.A.R. itself. This led the organization to play a role in the selection process and form a review committee. Other committee members included: Van Rensselaer, Mrs. Minnie Shenandoah (Onyota'a:ka) (Oneida), Chairman of the Cornell Indian Homemakers Board, and Walter Kennedy (Onöndowa’ga:’) (Seneca), Chairman of the Cornell Indian Boards. Even though Hodinǫ̱hsǫ́:nih leadership were involved in nominating and selecting candidates, departmental records and personnel files reveal that racial biases and prejudices impacted the application process.

Image: Mrs. Inez Ground, née Blackchief (Onöndowa’ga:’, Deer Clan), from Buffalo Courier Express, September 22, 1929.

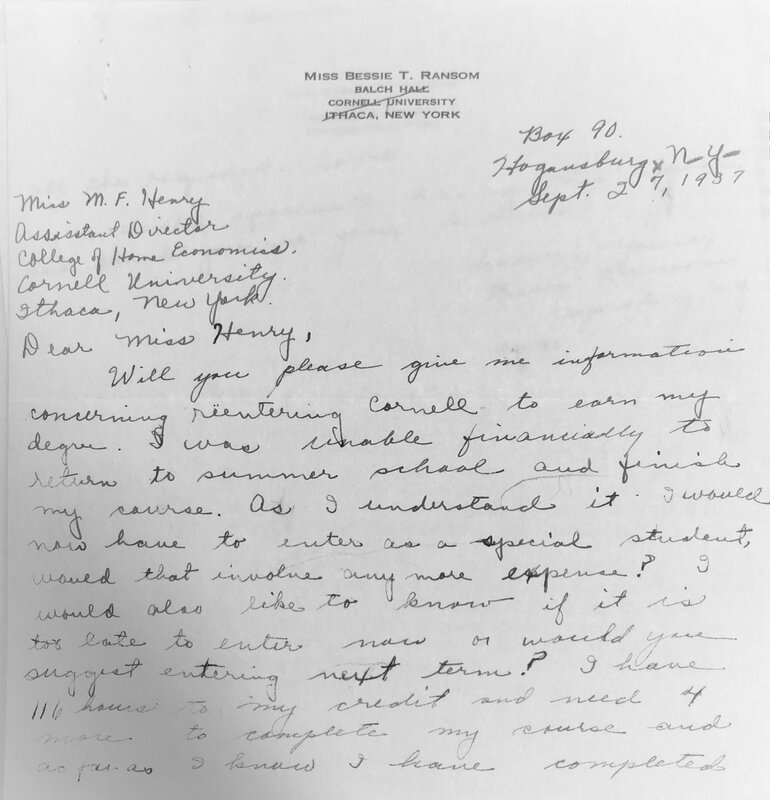

Bessie Tarbell, née Ransom (Kanien’kehá:ka)

Letters exchanged between Bessie Ransom (Kanien’kehá:ka) and Cornell administrators show that, despite receiving financial support, Cornell faculty and staff failed to support Indigenous students enrolled within the College of Home Economics. Initially, Mrs. Earl Burrows, Chairman of the Olive Whiteman Scholarship, advocated for Ransom's enrollment within the College of Home Economics. In August of 1933, she came to Cornell and began working towards her degree in home economics.

Ransom, however, left Cornell just 4 credits shy from graduating in 1937. According to her personnel file, she did not receive the full amount promised to her from the D.A.R. This led her to take out additional loans. To pay them off, she worked every summer, which in turn, impeded her from completing her coursework on time. By her junior year, Ransom was behind on the payments as well as her studies.

In 1936, Cornell administrator, Mrs. Grace, advocated on her behalf and wrote to Mrs. Burrows, inquiring as to whether the D.A.R. would be willing to send Ransom additional funds. While the College offered her an extension to pay back tuition, additional funds never materialized. Mrs. Grace suggested that Ransom reach out to Dr. Bates for assistance. However, notes within Ransom’s student file reveal that Dr. Bates refused to support her education “since she is a half breed and thus doesn’t identify herself as an Indian.”* These remarks illustrate the level of racism Hodinǫ̱hsǫ́:nih women faced upon entering the College as full-time students, as well as who was willing to support these women in their efforts to receive an education.

Image: Bessie Ransom '37 (Kanien’kehá:ka) possibly on Cornell's campus from #23-11-2679, Box 6, Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections, Cornell University Library.

Letter from Bessie Ransom to Mary F. Henry, September 27, 1937

Courtesy of Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections, Cornell University Library, College of Home Economics collection #23-2-749, box 62, folder 67.

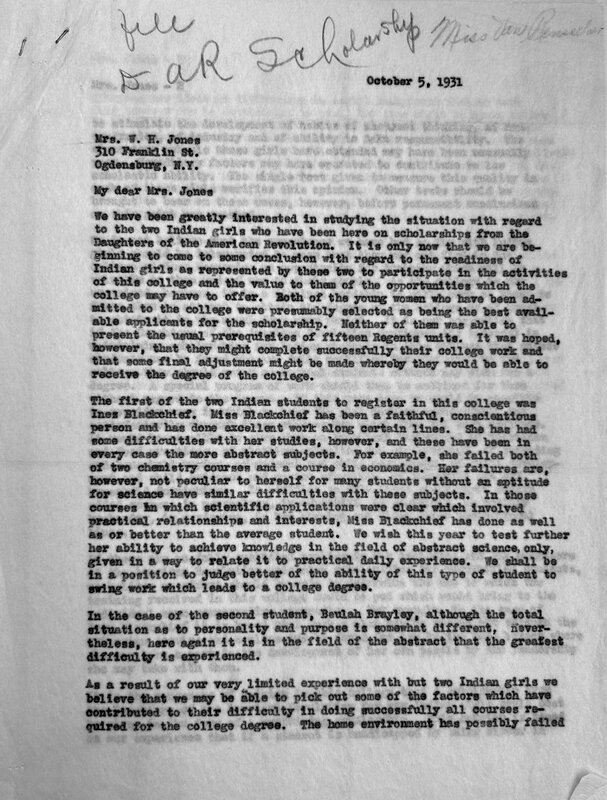

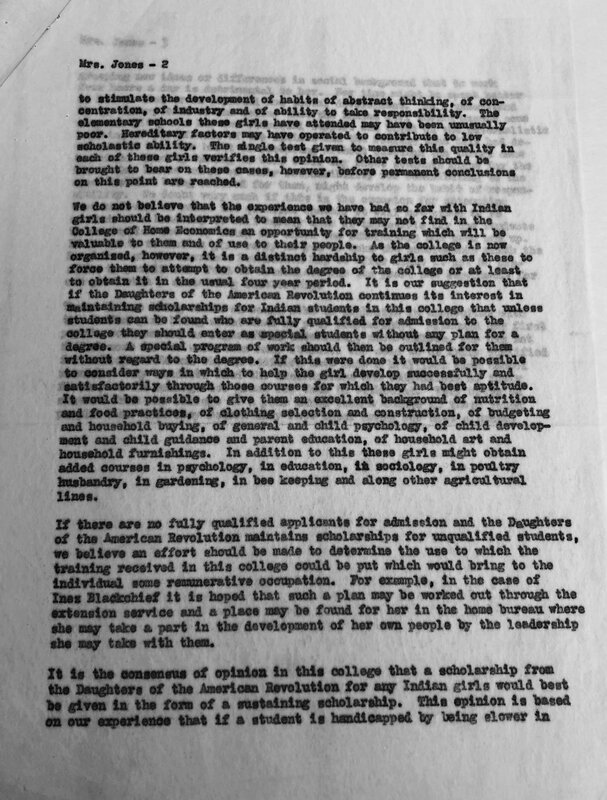

Barriers to Graduation

The racial biases and prejudices expressed within Ransom’s file are also conveyed within the College’s records. For instance, Cornell faculty expressed concern for the performance of two additional recipients: Beulah Brayley (Skarù·ręʔ) and Inez Blackchief (Onöndowa’ga:’, Deer Clan). According to the College’s records, Brayley only attended Cornell for one year, while Blackchief had already received a four-year degree from the University of Rochester and therefore was designated as a “special student.” Despite earning their high school diplomas and some college credit, correspondence between the College and the scholarship committee reveal that Cornell faculty and staff questioned Brayley and Blackchief’s presence on campus.

Letter to Mrs. W. H. Jones, October 5, 1931

Courtesy of Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections, Cornell University Library, College of Home Economics collection #23-2-749, box 59, folder 6.

In 1931, an unidentified Cornell employee explained that these women didn’t have the usual pre-requisites needed to enroll in the College as full-time students. First, they raised concern about Brayley and Blackchief’s ability to graduate and attributed this to the students’ limited knowledge of the hard sciences. They proposed that these women had difficulty in grasping abstract applications of scientific research and rigor, suggesting that the home environment, educational systems, or hereditary factors “possibly failed to stimulate the development of habits of abstract thinking, of concentration, of industry and of ability to take responsibility.” The employee concluded by requesting that the D.A.R. only fund “qualified” students in the future.

Not only did Cornell faculty and administrators reproduce and perpetuate hegemonic views of domesticity and epistemology; they also discriminated against those women who did not conform to the expectations of heteropatriarchal, white settler society. The suggestion that these women were not fit to study the hard sciences or abstract concepts due to “heredity factors” or their “home environment” was a critique of Indigenous kinship systems that took a communal approach to childrearing. Within matrilineal societies, the task of raising the next generation was a communal effort. The education of Hodinǫhsǫ́:nih youth did not occur within a classroom but through everyday observations and interactions across generation in an extended family.

Overall, the letter highlights the level of racism and discrimination Hodinǫ̱hsǫ́:nih women faced at Cornell. Even though Van Rensselaer and her colleagues have been credited with advancing opportunities for women in higher education, their use of scientific research to uplift “woman’s work” within the academy put forward a particular version of “work” and “science” that largely restricted women from claiming other sorts of expertise outside of the home.

Henrietta Guilfoyle, née Hoag (Onöndowa’ga:’, Beaver Clan)

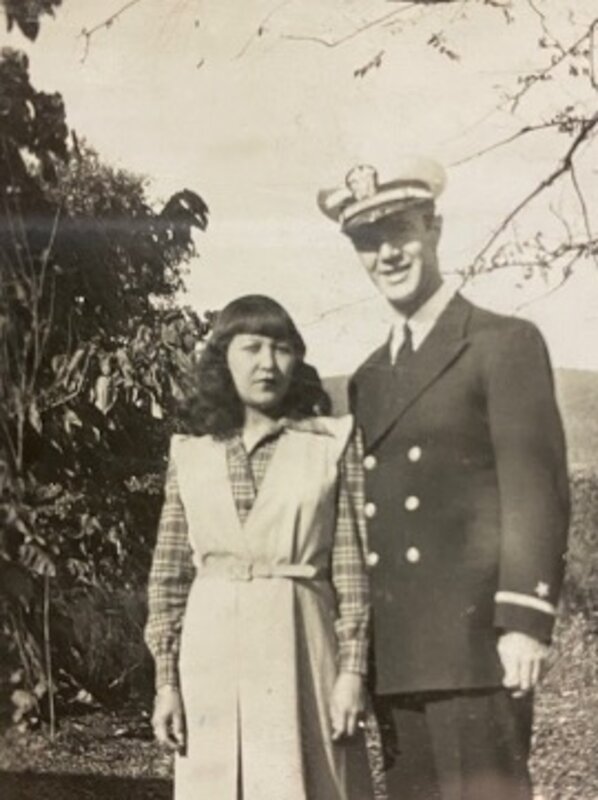

Despite the discrimination Hodinǫ̱hsǫ́:nih women faced at Cornell, one recipient, Henrietta Hoag, graduated within her degree in 1940. Beyond satisfying her general requirements, Hoag managed to assert her sovereignty as an Onöndowa’ga:’ (Seneca) woman of the Beaver Clan through her participation in several extracurricular activities on Cornell’s campus. This included her involvement in the fashion showcase, “Costumes of Many Lands,” which was organized by Professor Beulah Blackmore, Cornell’s first faculty member in clothing and textiles, during Farm and Home Week in the 1930s. The showcase intended to promote world peace by enhancing the audience’s understanding and appreciation of the traditions and customs of diverse peoples and places. Through Hoag’s involvement, this included the Hodinǫ̱hsǫ́:nih Confederacy. Hoag chose to don Onöndowa’ga:’ regalia for the 1937 showcase. However, the event was also problematic in that several white-appearing students were photographed in brown or blackface and dressed up in the fashions and identities that differed from that of their own. In fact, Hoag wore an Indian sari for the 1938 showcase rather than the clothing of her own Nation, which ultimately clashed with Professor Blackmore’s goal of fostering respect for the dress practices of diverse people.

Hoag also served as the Vice-President of the Cosmopolitan Club in 1939, the first club dedicated to international students at Cornell. Historian Alison Horrocks argued that, in the 1930s, international students and minorities were often viewed by Cornell faculty as outsiders. One place they found acceptance on campus was through clubs like the Cosmopolitan. This is supported by Hoag’s first son, the late Daniel E. Guilfoyle Jr., who attributed his mother’s success at Cornell to the long-lasting friendships she formed through the club. This is also how she met her husband, Daniel Guilfoyle Sr. By engaging in extracurricular activities, Hoag was able to find community outside of the College, as well as those structures that empowered her to assert sovereignty on campus.

Image: Henrietta Hoag '40 (Onöndowa’ga:’, Beaver Clan) from The Cornellian, 1940.

Henrietta Hoag on Cornell's Campus

Image 1: Henrietta Hoag in MVR 217 from #23-2-749, Box 39, Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections, Cornell University Library.

Image 2: Henrietta Hoag backstage at the 1938 installment of "Costumes of Many Lands" from #23-2-749, Box 114, Folder 25, Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections, Cornell University Library.

Image 3: Henrietta Hoag and husband, Daniel Guilfoyle Sr. from Daniel E. Gulfoyle Jr. and Daniel Guilfoyle III.

Image 4: Henrietta Hoag and classmate, Ruth Peterson Wismatt from Daniel E. Gulfoyle Jr. and Daniel Guilfoyle III

*The remarks made within Ransom’s student file suggest that she was the child of an interracial marriage. However, I have not been able to find any such documentation that indicates one of her parents was not Indigenous. Therefore, the claims made by Dr. Bates could have been informed by his own biases and pre-conceived notions of “Indian-ness.”

Archival Collections

Bessie Ransom Tarbell, Non-Grad, NYS College of Human Ecology Office of Student Services, #23-11-2679, Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections, Cornell University Library, Ithaca, NY.

“Bessie Ransom,” Box 62, Folder 67, New York State College of Home Economics, #23-2-749, Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections, Cornell University Library, Ithaca, NY.

“Native American Students,” Box 59, New York State College of Home Economics, #23-2-749, Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections, Cornell University Library, Ithaca, NY.

“D.A.R. Scholarship,” Box 60, Folder 184, New York State College of Home Economics, #23-2-749, Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections, Cornell University Library, Ithaca, NY.

Documentation and Review of Ethnic Collection, Folder 29, Box 11, Cornell University Department of Textiles and Apparel Records #23-19-2807, Cornell Rare and Manuscript Collection, Ithaca, New York.

Henrietta Hoag Guilfoyle ’40, NYS College of Human Ecology Office of Student Services, #23-11-2679, Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections, Cornell University Library, Ithaca, NY.

“Indian Student Scholarships,” Box 2, Dr. Earl Bates papers, #21-24-1605, Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections, Cornell University Library, Ithaca, NY.

Additional Sources

Guilfoyle Jr., Daniel E., personal communication, December 2022.

Horrocks, Allison. “Goodwill Ambassador with a Cookbook: Flemmie Kittrell and the International Politics of Home Economics.” PhD Dissertation, University of Connecticut, 2016.

“Indian Girl Will Receive Scholarships,” Ithaca Journal, February 8, 1929, 9.

“Inez Blackchief at Cornell, First Indian Girl to Win Full Scholarship, Is Interviewed,” Ithaca Journal, November 2, 1929, 2.

“New York Indians Attend Farm Meet,” Ithaca Journal, January 27, 1930, 2.

“Two Indian Girls are Home Economics Students,” Cornell Countryman, November 1930, 54.