Categories of Readership

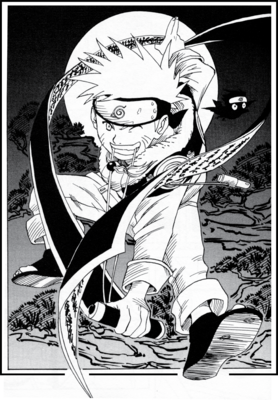

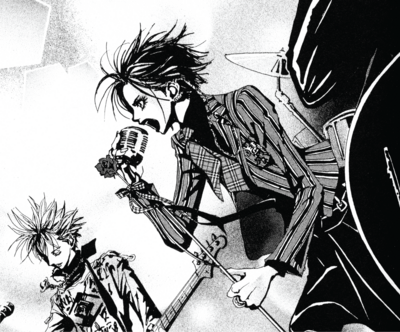

By the mid-1960s, as manga production grew standardized within the booming Japanese publishing industry, four commercial categories of readership, based on age and gender, came to be strictly applied to the works: shojo (adolescent female), josei (adult female), shonen (adolescent male), and seinen (adult male). Generally speaking, works for adolescents are more innocent, simplistic in focus, and less socially engaged (for example, Naruto), whereas works for adults involve the darker, more complex themes of life (social and psychological issues, including sexuality, crime, and violence) introduced by gekiga (for example, Nana). Though these readership categories are not strictly proscriptive, the lead protagonists in works of each type usually match the gender and age of their projected audience, as do the nature of their concerns, and, generally speaking, the degree to which the plot hinges on action/event versus psychology/character. Even illustrative styles vary by category, with shojo manga, for example, tending towards more ornate, flowery imagery, while works for adults tend to have heavier, more detailed presentations. Such categories, for manga creators, can be a double-edged sword, on the one hand providing a readymade register for projections of plot and characters, as well as a strong intertextual basis, but on the other limiting the freedom of creative possibility by forcing artists to operate within modes artificially designated according to assumptions regarding age and gender.