Education

In the nineteenth century, English society assumed women to be intellectually inferior to men, and that too much education would "ruin" girls, making them unfit for marriage and motherhood. Consequently, most middle and upper middle class girls were taught little beyond basic reading and writing, and instead were trained in "accomplishments," such as music, drawing, and dancing, to better attract eligible suitors.

Yet women who hoped to have their writing taken seriously in the same arena with men’s needed to attain a comparable level of education–education that was all but closed to them for most of the century.

Mary Astell

Since the English Renaissance, women had made cautious but steady advances toward educational equality. When English universities finally began relaxing restrictions on female access to higher education in the 1870s, the move capped centuries of debate over women’s education.

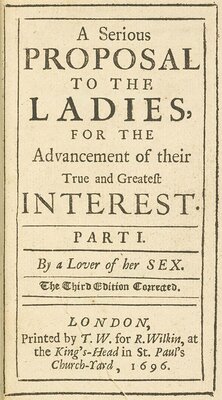

Mary Astell (1668-1731) was one of the first English women to advocate the idea that women were just as rational as men, and just as deserving of education. First published in 1694, her Serious Proposal to the Ladies presents a plan for an all-female college where women could pursue a life of the mind. Well-reasoned and articulate, Astell’s ideas concerning female education were original and controversial. She was widely read in her own time and is hailed today as one of the first feminists.

Mary Wollstonecraft

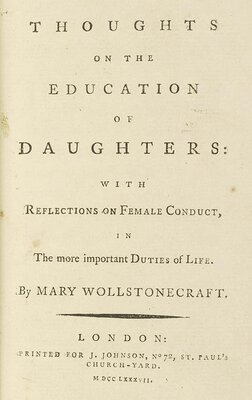

Writing almost one hundred years after Astell, Mary Wollstonecraft also addressed the proper duties and education of women.

Thoughts on the Education of Daughters (1787) was Wollstonecraft’s first book. In many ways typical of eighteenth century conduct literature for women, the book reiterates conventional ideas regarding women's domestic and moral duties. Yet the author also asserts that, as independent and intellectual beings, women deserve better access to education.

J. S. Mill

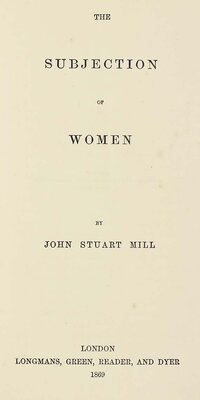

The social reformer John Stuart Mill was one of the most outspoken advocates for women’s rights in the nineteenth century. His controversial work, The Subjection of Women, argues for the perfect legal and social equality of the sexes–a radical idea in Victorian England.

Hitchin College for Women

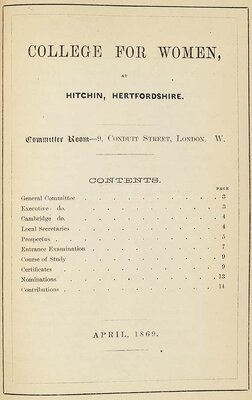

Hitchin College for women was the precursor to Girton, the first women’s college at Cambridge University, which was founded in 1869 by the pioneering education reformer Emily Davies. With the opening of Girton, women were allowed to attend Cambridge faculty lectures, live in college, and sit for exams. For the first time, women were granted the formal educational opportunities that for centuries had been the exclusive preserve of men. A second women’s college at Cambridge, Newnham, was founded shortly thereafter.

Emily Davies battled to keep the curriculum and exams for women just as challenging as those required of men. The Hitchin Prospectus shown here presents a program of study for women preparing to take university entrance exams.

Get You to Girton…

Despite expanded access to university classes in the 1870s, higher education for women remained controversial. Even though women attended the same lectures and passed the same examinations as men, not until the twentieth century were they granted the degrees they had earned.

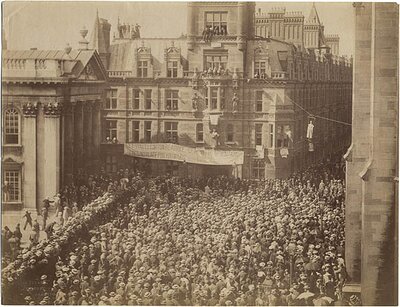

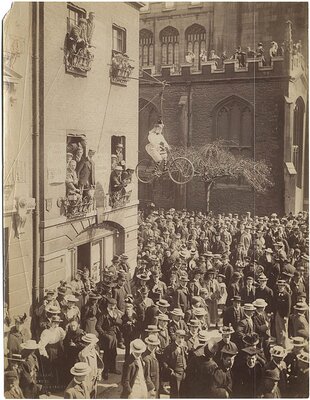

These photographs were taken on May 21, 1897, when Cambridge University voted on whether or not to admit women to full university membership. The women were defeated, 1,713 to 662. As these images show, the issue provoked a massive protest by male undergraduates. The banner across the front of the Caius College windows reads:

Get you to Girton Beatrice Get You to Newnham Here’s No Place for You Maids.

Not until 1923 did Cambridge grant degrees to women. It did not recognize them as official members of the University until 1948.

College Girl Fiction

The few women who did manage to attend college in the nineteenth century displayed their learning at the risk of being labeled "unwomanly" by Victorian culture.

Novels that dealt with higher education for women often confirmed the Victorian view of educated women as aberrations, portraying them as sexless, mentally disturbed, or dangerous.