"I will be heard!": Prominent Abolitionists

In the 1830s, American abolitionists, led by Evangelical Protestants, gained momentum in their battle to end slavery. Abolitionists believed that slavery was a national sin, and that it was the moral obligation of every American to help eradicate it from the American landscape by gradually freeing the slaves and returning them to Africa.. Not all Americans agreed. Views on slavery varied state by state, and among family members and neighbors. Many Americans—Northerners and Southerners alike—did not support abolitionist goals, believing that anti-slavery activism created economic instability and threatened the racial social order.

But by the mid-nineteenth century, the ideological contradictions between a national defense of slavery on American soil on the one hand, and the universal freedoms espoused in the Declaration of Independence on the other hand, had created a deep moral schism in the national culture. During the thirty years leading up to the Civil War, anti-slavery organizations proliferated, and became increasingly effective in their methods of resistance. As the century progressed, branches of the abolitionist movement became more radical, calling for the immediate end of slavery. Public opinion varied widely, and different branches of the movement disagreed on how to achieve their aims. But abolitionists found enough strength in their commonalities—a belief in individual liberty and a strong Protestant evangelical faith—to move their agenda forward.

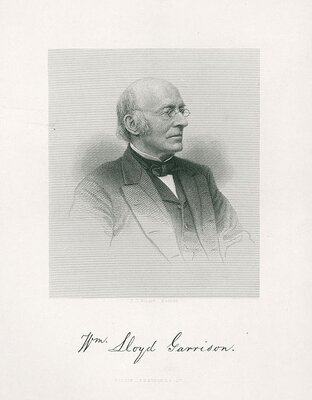

William Lloyd Garrison

William Lloyd Garrison (1805-1879), the lightning rod of the abolitionist movement, promoted “moral suasion,” or nonviolent and non-political resistance, to achieve emancipation. Although he initially supported colonization, Garrison later gave his support to programs that focused on immediate emancipation without repatriation. In 1831, he began publishing The Liberator, the single most important abolitionist publication, and later led the American Anti-Slavery Society. His vociferous language and his very presence outraged anti-abolitionist Northerners who attacked him, sometimes physically, with mob-driven violence. His avid support for a woman’s right to participate in the movement and his attack on the American Constitution as a pro-slavery document created irretrievable divisions in the abolitionist movement. However, his unflagging conviction and his influence in promoting “immediatism” shaped the course of abolitionism in America.

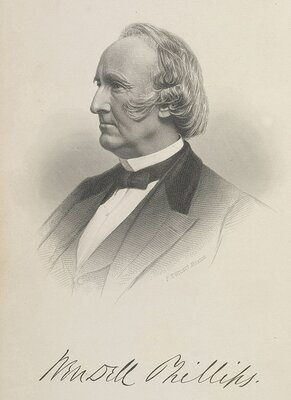

Wendell Phillips

Wendell Phillips (1811-1884) was one of the movement’s most powerful orators. The Harvard-educated lawyer came from a wealthy and influential Boston family, many of whom were appalled by his activism in support of the abolitionist cause. However, he was undaunted in his work and was thrust into prominence when he gave a riveting speech in Boston’s Faneuil Hall in defense of Elijah Lovejoy in 1837. The Rev. Lovejoy had been murdered for his repeated attempts to run a printing press sympathetic to the abolitionist cause. Phillips used plain, yet metaphorical language to convey his message. He also gave generously to abolitionists in need of financial assistance.

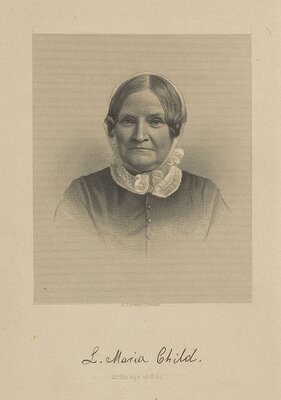

Lydia Maria Child

Novelist, scholar, and activist for women’s rights, Lydia Maria Child (1802-1880) became an abolitionist after she began reading Garrison’s news journal, The Liberator. In 1833, Child wrote “An Appeal to that Class of Americans Called Africans,” an anti-slavery tract in which she declared her willingness to battle for emancipation. Her new abolitionist rhetoric so repelled readers that Child's books sold poorly, and she could not find a publisher willing to accept her work. From 1841-43, Child was the editor of the National Anti-Slavery Standard, the American Anti-Slavery Society’s newspaper. She later resigned because of infighting among the society's members, who were divided in their support for the diverging philosophies, “moral suasion” and political persuasion. Child revitalized her role as an opponent of slavery after the passage of the Fugitive Slave Law in 1850 and John Brown’s raid on Harper’s Ferry in 1859. She continued publishing letters, edited Harriet Jacob’s Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, and wrote primers and anti-slavery tracts to combat racial injustice.

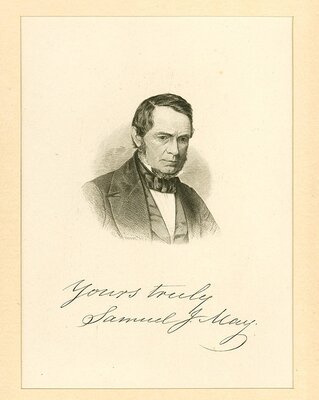

Samuel J. May

Samuel May’s life was forever changed when he heard William Lloyd Garrison lecture about immediate, unconditional emancipation without expatriation in 1830. May (1797-1871) wrote of that experience, “my soul was baptized in his spirit, and ever since I have been a disciple and fellow-laborer of Wm. Lloyd Garrison.”

May, a Unitarian minister, was a pacifist and practiced non-violent resistance by lecturing, acting as a general agent of the Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society, and sheltering slaves on the Underground Railroad. In one notable case, May helped to liberate William “Jerry” Henry, who had been taken into custody in Syracuse under the Fugitive Slave Law, and was to be returned to slavery. After the “Jerry Rescue,” a pro-slavery mob attacked May and other rescuers and burned the unwavering May in effigy.

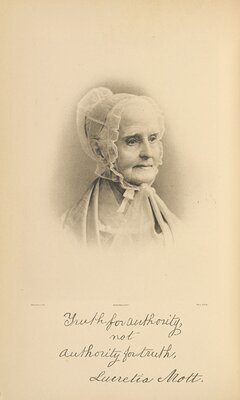

Lucretia Mott

Lucretia Mott (1793-1880) was a Quaker and a “non-resistant” pacifist who was committed to black emancipation and women’s rights. As a woman, her role in official abolitionist movements was fraught with difficulties. In 1840, she and six other American female delegates to the World Anti-Slavery Convention in England were refused seats. Because of her opposition to violence of any kind, Mott did not support the Civil War as a means of liberating slaves. She did, however, welcome the War’s hastening of emancipation. Of her principles she wrote, “I have no idea, because I am a non-resistant, of submitting tamely to injustice inflicted either on me or on the slave. I will oppose it with all the moral powers with which I am endowed. I am no advocate of passivity.”

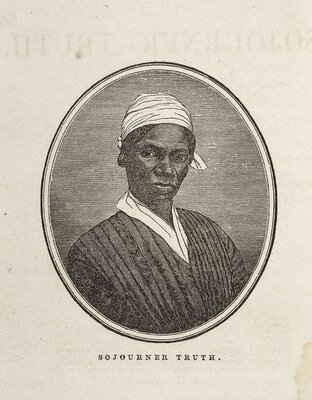

Sojourner Truth

Despite her inability to read or write, Sojourner Truth (ca. 1797-1883) had a commanding presence and considerable oratorical powers. She was one of the best known and esteemed black women of the nineteenth century. Born a New York slave and given the name Isabella Baumfree, Sojourner Truth gained her freedom when New York abolished slavery in 1827. A pacifist, she transformed herself into an activist for abolitionism and proclaimed her new identity by changing her name to Sojourner Truth. Her anti-slavery activities included recruiting black troops, publishing her narrative, and winning a civil rights lawsuit. Her circle of influence included both black and white allies as well as several presidents. Sojourner Truth drew upon her experience as a black woman and former slave, advocating the abolition of slavery, civil liberties for African Americans, and women’s rights.

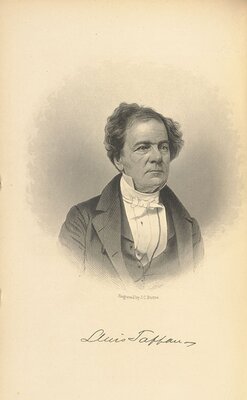

Lewis Tappan

Lewis Tappan (1788-1873), a wealthy merchant from a strong Calvinist family, is best known for his role in organizing the defense of Joseph Cinque in the Amistad trial. Tappan also funded anti-slavery journals and helped to form the American Anti-Slavery Society, which he later abandoned because of his disapproval of women’s involvement in the society. Tappan and other disaffected former members of the American Anti-Slavery Society formed the American and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society, which employed political abolitionism. After the passage of the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850, Tappan supported the Underground Railroad, and he fought for black civil rights in the North. His abolitionist deeds were often met with hostility, which extended as far as the destruction of a church built by Tappan and his brother.

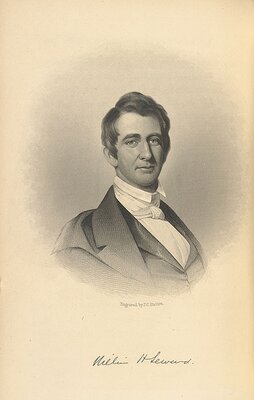

William Seward

William Seward (1801-1872), of Auburn, New York, served as governor of New York from 1838 to 1842. He was elected to the U.S. Senate as a Whig party member in 1847, primarily because of his anti-slavery stance. He fought a hard political battle against the Missouri Compromise of 1850 and in favor of the admission of California as a free state.

Seward later softened his stance on slavery to appease Southerners during his unsuccessful run for president on the Republican ticket. Lincoln made Seward his Secretary of State, and called upon Seward to help compose the Emancipation Proclamation. Seward also sheltered slaves on the Underground Railroad. He admired the work of Harriet Tubman, and sold her the land in Auburn, New York, where she built her home.

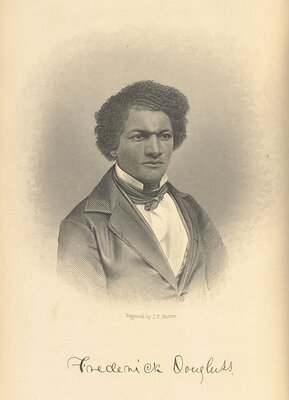

Frederick Douglass

As a lecturer, writer, editor and ex-slave, Frederick Douglass (ca. 1818-1895) emerged as the most prominent African American of the nineteenth century to fight for racial justice. Under Garrison’s mentorship, Douglass adopted “moral suasion” as an abolitionist strategy. Impatient with this approach, Douglass later broke from Garrison, believing that political activism was the only way to achieve freedom. Although vehement in his rhetoric, Douglas refused to use violence. Indeed, he refused to defend or take part in John Brown’s raid at Harper’s Ferry. Douglass wrote three autobiographies, edited four newspapers, lectured nationally and internationally, and recruited black soldiers for the Civil War. He advised and pressured Lincoln to make slavery the single most important issue of the Civil War and remained committed to integration and civil rights for all Americans throughout his life.

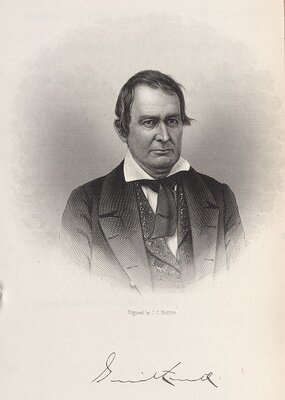

Gerrit Smith

Gerrit Smith (1797-1874) was a wealthy abolitionist from Utica, New York. His conversion to abolitionism occurred in 1835, when he attended an abolitionist conference in Utica, New York. The meeting was disrupted by a violent mob of anti-abolitionists. Consequently, Smith offered his Peterboro, New York estate to house the conference and, there, made a powerful speech on behalf of the cause. He became the president of the New York Anti-Slavery Society for three years. Smith served as Station Master of the Underground railroad and sold portions of his land to fugitive slaves for the nominal fee of one dollar. Gerrit Smith was also one of the Secret Six, a group of supporters who gave financial assistance to John Brown for his raid at Harper’s Ferry. Smith ran for president three times and was the only abolitionist to hold a Congressional office.

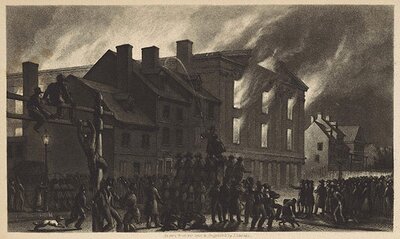

Pennsylvania Hall

On May 17, 1838, an abolitionist convention was held in Philadelphia’s Pennsylvania Hall. A large mob burned the building to the ground, protesting against abolitionism. The city was plagued at the time with anti-black and anti-abolitionist violence, particularly from Philadelphian workers who feared that they would have to compete for jobs with freed slaves. Pennsylvania Hall had been open only three days when it fell.

Later that year, the Pennsylvania Hall Association documented the destruction of Pennsylvania Hall in this publication, proving that the mob’s violent action against them was unprovoked.