Uncle Tom's Cabin

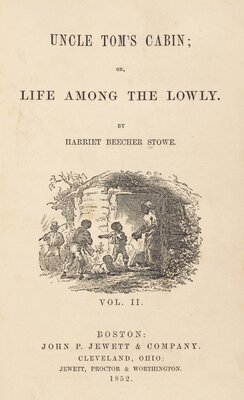

In 1850, Congress enacted the Fugitive Slave Law, which permitted slave owners to apprehend and recover their “property” from free states without process of law. Abolitionists fought the law, which angered even moderate Northerners. In response, Harriet Beecher Stowe began work on what would become one of the best-known, most hotly-debated, and most enduring pieces of fiction in American history. Stowe’s highly sentimental and melodramatic tale, Uncle Tom’s Cabin, was first published in forty serial issues of the abolitionist weekly the National Era beginning in June of 1851. It was published as a two-volume book by John Punchard Jewett in March of 1852. The story’s scathing indictment of slavery’s cruelty evoked horror in the North, and outrage in the South over what Southerners perceived as an unfair condemnation of their “peculiar institution.”

Uncle Tom’s Cabin was one of the most contested novels of its time. Initially, the novel was criticized by whites who thought Stowe’s portrayal of black characters was too positive, and, later, by black critics who believed these same characters were oversimplified and stereotypical. Uncle Tom’s Cabin also gave birth to the racial epithet “Uncle Tom,” which is still an insult today.

Despite the criticisms and controversies surrounding the novel, Uncle Tom’s Cabin transcended its fictional genre, and brought the urgent issue of slavery’s brutality into the homes of white Americans. It galvanized many into becoming abolitionist sympathizers, if not activists themselves.

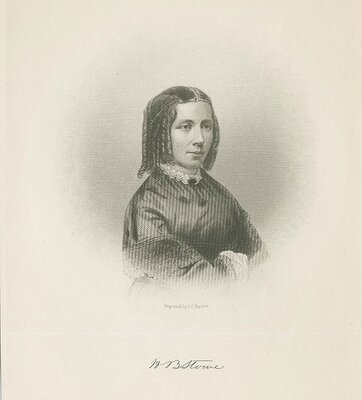

Harriet Beecher Stowe's Uncle Tom's Cabin

Born in 1811 to a strict Calvinist family in Litchfield, Connecticut, Harriet Beecher Stowe quickly rose to fame after publishing her most famous work in 1852. Recently, renewed interest in the sentimental novel, and in the impact of Stowe’s novels on her contemporaries, has helped to revitalize the author’s work and to secure its place in the American literary canon.

Initially, publishers shied away from Stowe’s novel because of its regional divisiveness; but finally John Jewett, encouraged by his wife, decided to publish the book. Stowe’s two-volume novel sold a staggering 10,000 copies in its first week, and 300,000 copies by the end of its first year.

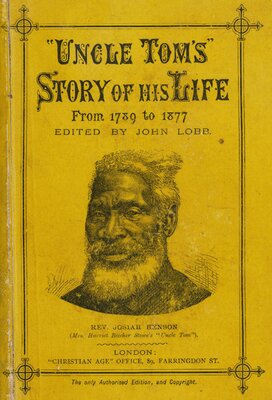

London Edition

International editions of Uncle Tom’s Cabin were rushed into print, and sales flourished. Indeed, the novel was even more popular in England than in the United States. In the absence of copyright laws, heavy international demand for text often resulted in unauthorized printings, and Stowe made little profit from these editions.

Uncle Tom Sparks Public Debate

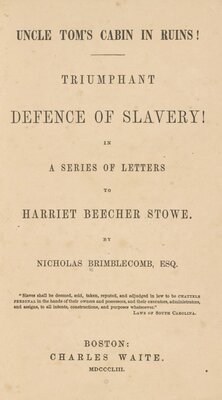

As Uncle Tom’s Cabin’s popularity soared, the novel provoked heated debate over the authenticity of Stowe’s depiction of slavery, and whether her characters were “real.” Stowe’s opponents argued that her portrayal of slavery was misleading and exaggerated. Her critics began publishing pro-slavery tracts to refute the facts presented in the novel. Stowe responded by releasing her own book, The Key to Uncle Tom’s Cabin, which provided documentation on the facts in her novel, and named the books and the people that served as her sources of information. Stowe’s sources remain controversial, since she conducted much of her research on slavery only after the novel was published.

Uncle Tom's Cabin in Ruins

Brimblecomb’s book completely opposed Stowe’s characterization of slavery and its upholders. The author’s premise was that slaves were property, and that no one had the right to interfere with another person’s property. He used arguments based on Biblical doctrine to support his premise. Brimblecomb believed in black inferiority, in the benevolence of the slave trade, and in the idea of slavery as a source of national pride.

The Real Uncle Tom?

According to an editorial note by John Lobb, Stowe read Henson’s story in 1849 and later met him and the “real” George Harris. Their stories served as the source material for Uncle Tom’s Cabin. Some critics dispute this claim, declaring that Stowe wrote her own story before she read Henson’s.

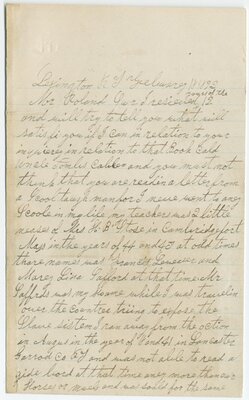

In his letter to a Mr. Roland, Lewis George Clark, who claims to be the “real” George Harris of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, gives a detailed account of incidents that he says inspired situations in Stowe’s book, and cites conversations he had with Stowe before and after the book was published.

Gift of Gail ’56 and Stephen Rudin

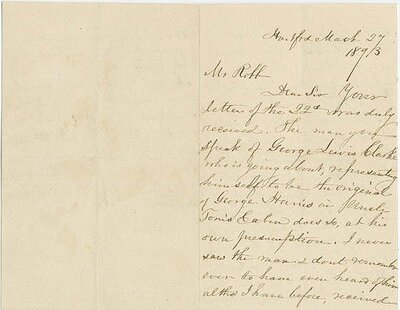

Stowe’s 1893 letter to a Mr. Robb denies the claim that Lewis George Clark was the real George Harris. She writes, “I never saw the man and don’t remember ever to have even heard of him . . . one thing certainly is true—the man was not in my mind at the time of writing Uncle Tom’s Cabin. Neither he, or any other man stood for the character of George Harris….”

Gift of Gail ’56 and Stephen Rudin

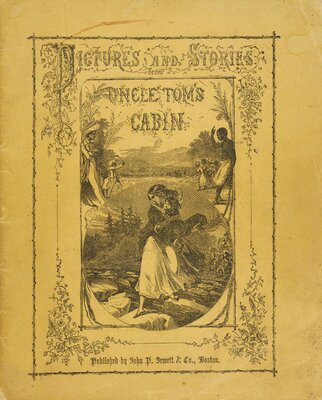

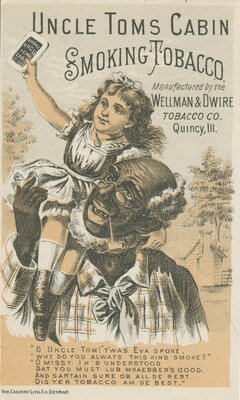

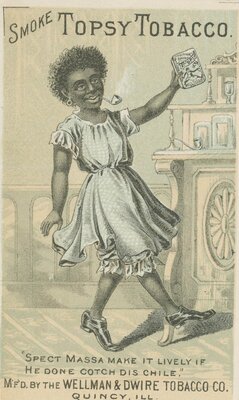

Variations on Uncle Tom

Because of Uncle Tom’s Cabin’s phenomenal success, the story was commodified in many forms. Music, plays, children’s books, and numerous translations and illustrated versions of the book appeared. Images and characters from the novel were used to sell products and services, including those without the remotest connection to it.

This abridged book of prose and verse for children was adapted from Uncle Tom’s Cabin and intended to encourage young readers to sympathize with its enslaved characters.

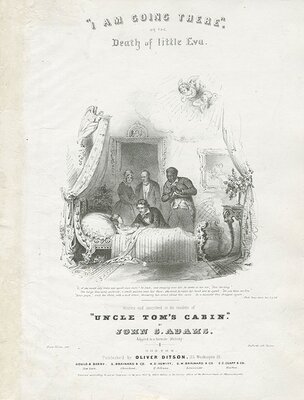

Musical Uncle Tom

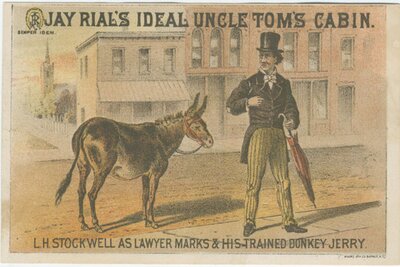

This is a promotional tour card for a post Civil War production of a musical adapted from Uncle Tom’s Cabin.

Sheet music: gift of Gail ’56 and Stephen Rudin