In Their Own Words: Slave Narratives

For many slaves, the ability to read and write meant freedom—if not actual, physical freedom, then intellectual freedom—to maintain relationships amongst family members separated by the slave trade. A few wrote slave narratives, which, when published, powerfully exposed the evils of slavery. For slaves and their teachers, the exercise of reading and writing was a dangerous and illegal one. In most southern states, anyone caught teaching a slave to read would be fined, imprisoned, or whipped. The slaves themselves often suffered severe punishment for the crime of literacy, from savage beatings to the amputation of fingers and toes.

Although some masters did teach their slaves to read as a way to Christianize them, most slave owners believed that teaching such skills was useless, if not dangerous. They assumed that slaves had no use for reading in their daily lives, and that literacy would make them more difficult to control, and more likely to run away.

For those who managed to become literate and escape to freedom, the ability to write would spark the growth of a powerful genre of literature: the slave narrative. For the abolitionist movement, slave narratives would become tremendously effective weapons in attacking the institution of slavery. Despite the danger of physical punishment and the threat of capture for the authors of slave narratives, these men and women took great risks to empower themselves, and in some cases, achieved freedom.

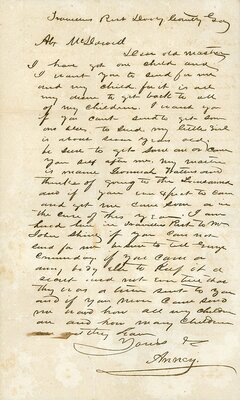

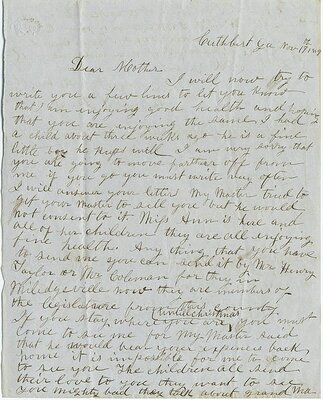

Separation

Slave letters reveal a great deal about the emotional lives of slaves and the cruelty inherent in the slave system. Although most slaves were not literate, those who could write, or who had access to literate friends, have left behind wrenching documents that express the anguish of parents divided from their children, and the longings family members experienced for loved ones forcibly separated from them.

Slave Narratives

Written by slaves or by sympathetic white proxies, slave narratives offer vivid accounts of journeys, survival and endurance. Approximately 6,000 slave narratives were published in 250 years, but none were more popular than those published during the antebellum period. 12% of all slave narratives were written by women, whose stories attested to sexual exploitation and forced separation from their children. Giving a voice to the voiceless, slave narratives became the cornerstone of modern-day African American autobiography.

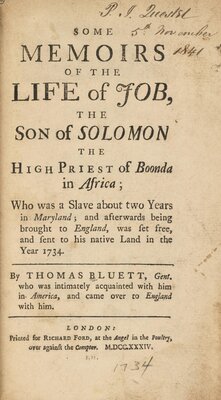

Life of Job

This eighteenth-century narrative, written by Thomas Bluett at the request of Job, is one of the first slave narratives ever published. Job’s purpose in telling the story of his life in Africa, his lineage, and religion is to prove his own humanity and by extension, the humanity of African people. The white audience Job reached was largely wealthy, middle-class and European.

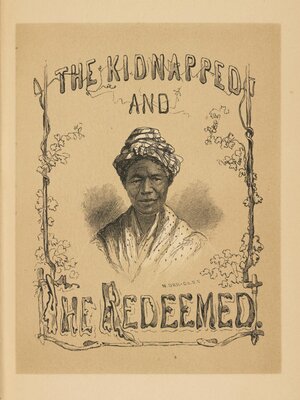

Peter Still

Kate Pickard wrote down the harrowing tale of the life of Peter Still, who endured countless trials in his ultimately successful quest to buy freedom for his wife and children. Kate Pickard functioned as the “authenticator” of this slave narrative. Her aim was to give Northerners “new illustrations of the horrors that ‘peculiar institution’ which has well nigh subjugated to itself our entire republic.”

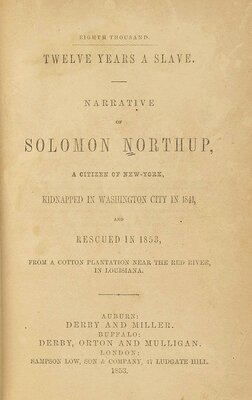

Solomon Northup

Northup’s first person account of his journey out of slavery utilizes the most frequently employed elements of male slave narratives: a strong and self-sufficient hero who overcomes numerous attempts on his life by using his great physical strength.

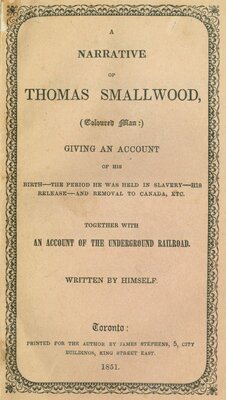

Thomas Smallwood

The expatriate Smallwood bitterly describes the treachery he encountered from supposed friends and foes as an agent in the anti-slavery movement. He is prophetic in his views of America’s slaveholding future: “…the long suspended blow against that republic and the final emancipation of its victims are close at hand, and will be attended with a terrible and bloody breaking up of their system.”

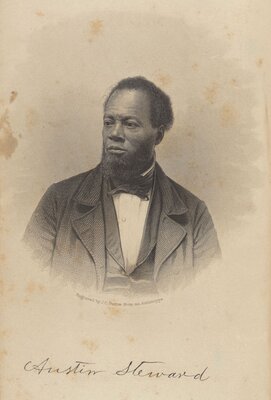

Austin Steward

Austin Steward gives a clear account of the violence of slavery. Of the overseer’s brutality he says: “The overseer always went around with a whip. . . made of the toughest kind of cowhide, the but-end of which was loaded with lead… This made a dreadful instrument of torture, and, when in the hands of a cruel overseer, it was truly fearful. With it, the skin of an ox or a horse could be cut through. Hence, it was no uncommon thing to see the poor slaves with their backs mangled in a most horrible manner.”

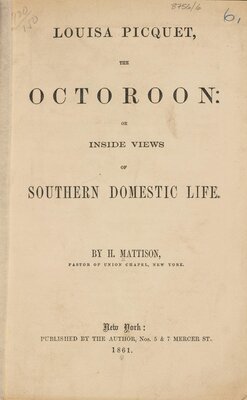

Louisa Picquet

Written in a question and answer format, this female slave narrative reveals the complexities of miscegenation, the constant threat of rape, and the moral conflict of bearing children and being forced to live outside the bounds of marriage.

Samuel J. May Anti-Slavery Collection.