American Taste & Tradition

America's first European colonists encountered a continent already peopled with native food cultures and traditions, but they brought their European tastes and food conventions with them.

Although there were plenty of edible plants and animals here, American colonial food remained grounded mainly in British traditions until well into the 19th century—dominated by meats and breads, with very little use of fruits and green vegetables.

American food began to distinguish itself from its European and British origins at the end of the 18th century, as the young nation developed its own cultural, political, and domestic traditions. Soon, American cookbooks would reflect the use of bountiful native ingredients, such as corn, squash, and cranberries.

Until the last decades of the 19th century, most American cookbooks emphasized practicality and economy over luxury and elegance. The often primitive conditions of rural and frontier life demanded a survivalist approach to cooking and domesticity. Toward the end of the century, however, food habits came to reflect the country’s growing prosperity, with an increasing interest in French cooking, elegant entertaining, and fine dining.

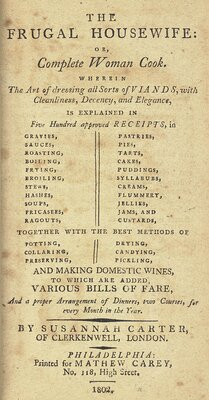

The Frugal Housewife

The first cookbooks published in America were reprinted from English works. Susannah Carter’s The Frugal Housewife, originally published in London, was one of the first cookbooks printed in America. Her work features a full alphabetical index for more than 500 recipes, providing a fascinating snapshot of mid-18th century Anglo-American culinary practice.

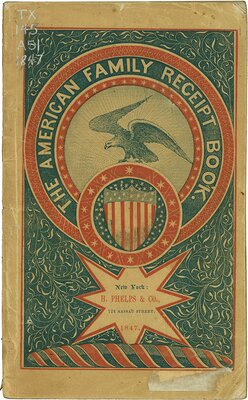

American Recipes, 1847

The patriotic covers on this 1847 American cookbook reflect a growing national pride in a distinctly native approach to food and domestic economy. The book contains advice on everything from how to revive tainted meat, to how to rid the house of rats, to how to jump out of a wagon.

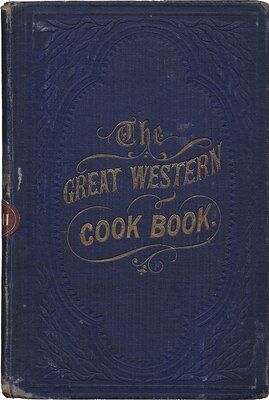

American Regional Cuisines

American regional cuisines began to emerge by the mid-19th century. Written for the benefit of Western housewives, this book of recipes shows how ingredients and cooking methods were adapted as settlers migrated west. It includes recipes for "California Soup," "Corn-meal Batter Cakes," and "Veal—Western Fashion."

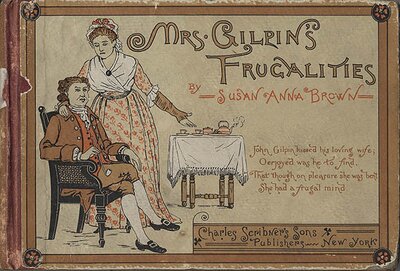

Home Economy

This book is typical of the frugal practicality of most American cookbooks in the 19th century.

The Boston Cooking School

Founder and first director of the Boston Cooking School (1879-1885) Mary J. Lincoln aimed to bring a standard cooking curriculum into the home. Lincoln’s cookbooks were used and extensively cited by leaders of the home economics movement, which sought to apply scientific principles to improve nutrition and hygiene in the American home.

Fannie Farmer

Influential graduates of the Boston Cooking School—such as Fannie Farmer—went on to spread the school’s teachings in restaurants, classes, and a variety of publications. Their recipes marked a new era of professionalism, detail, and clarity in cookbooks, establishing the format we know today.

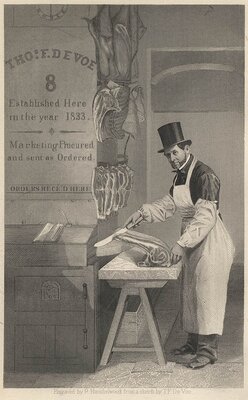

The American Marketplace

Guides to Eastern produce and meat markets trace the growing wealth and variety of food available to American consumers after the Civil War. This guide was written by Thomas De Voe, head butcher of New York City’s historic Jefferson Market, which still exists today.

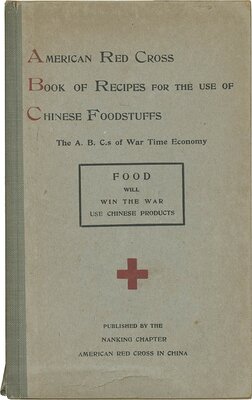

Food Will Win the War

Food can define cultural boundaries and reinforce communal identities. This power is perhaps most evident when starkly different food traditions collide.

This guide to Chinese food was written by women of the American Red Cross stationed in Nanking during World War I. It admonishes Americans overseas to use local food products, so as to help save home food imports for the allied armies. In the book’s preface the author, Mrs. J. H. Reisner, rallies her colleagues to do their patriotic duty by adapting Chinese ingredients to Western tastes.