Gastronomy

Before the 19th century, great cooking was experienced almost exclusively in the private homes of the wealthy. This began to change after the French Revolution, when the fall of the aristocracy left a number of talented chefs unemployed.

Many of these chefs later opened some of the Continent’s first fine restaurants, winning devoted followers among the French bourgeois, who were eager to display their elevated tastes in food and fashion. This phenomenon produced some of the first "star" chefs, many of whom published compendiums of their repertoires and opinions. Their cookbooks not only served as self-advertisement, but also enabled the newly rich to reproduce the professional dining experience in their own private homes.

Some of these French chefs went to work for ambitious restaurateurs in major cities like New York and London, or cities newly flush with wealth, such as post-Gold Rush San Francisco. The influence of these chefs slowly permeated American culture, exposing growing numbers to French cooking techniques and dining manners.

Most important, these 19th century French chefs helped to codify what came to be known as French classical cooking, their books defining by systematic repetition the basic French recipes and technique. Sauces such as vélouté, hollandaise, and mayo-nnaise, for example, were refined and regularized during this period.

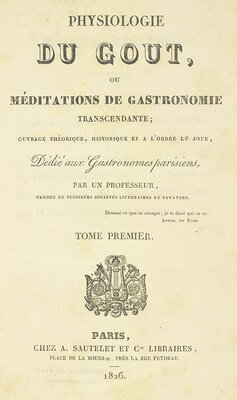

Physiologie du Goût

The roots of gastronomy in America can be traced to 19th century France. Jean Anthelme Brillat-Savarin (1755-1826) was a politician, judge, and writer. But he is most remembered for what many consider to be the bible of gastronomy, Physiologie du Goût ou: Méditations de Gastronomie Transcendante. Brillat-Savarin was the first writer to provide a systematic analysis of the pleasures of eating–a gastronomic code from which countless fellow gourmands drew inspiration. Published shortly before his death, Brillat-Savarin’s philosophy of food conisseurship and fine dining was an immediate smash success, making him famous overnight.

The work remains a culinary touchstone to this day, and has appeared in dozens of editions and translations. Some of Brillat-Savarin’s aphorisms have entered into popular culture, such as his "Dis-moi ce que tu manges, je te dirai ce que tu es," or, "Tell me what you eat, and I will tell you what you are." English speakers regularly repeat Brillat-Savarin’s idea with the phrase "you are what you eat."

The Pleasures of Dining Out

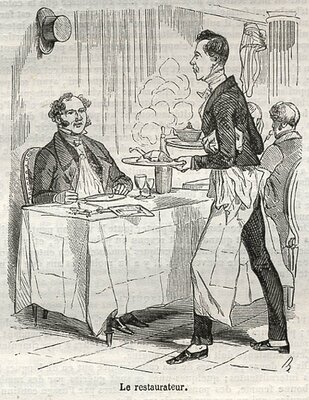

This engraving of an expectant diner appeared in a popular illustrated edition of Brillat-Savarin’s famous work.

Published 25 years after the first edition, this popular edition demonstrates the longevity and wide appeal of the text. In the preface, the editor calls the book a "monument of 19th century literary culture…a perfection of stylistic originality and form."

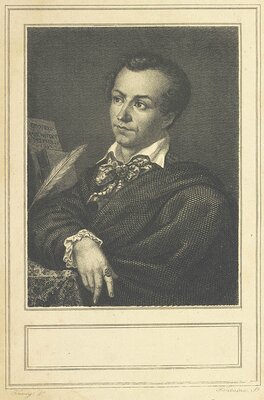

Marie Antonin Carême

Marie Antonin Carême (1783-1833), often called the father of French cuisine, was one of the most prolific food writers of the 19th century. During his long career, he was chef for Talleyrand, Czar Alexander I, George IV, and Baron Rothschild. Carême codified the four primary families of French sauces that form the basis of classic French cooking to this day–espagnole, vélouté, allemande, and béchamel. Thanks to Carême’s books, French chefs working at home and abroad had a basic, shared vocabulary to refer to in their cooking.

L’Art de la Cuisine Français au Dix-Neuvième Siècle is an exhaustive survey of classic French cooking. Published near the end of Carême’s career as a master pâtissier and chef, the three-volume work was completed after his death by his friend and colleague Armand Plumerey.

The Art of Dessert

Featuring baroque, labor intensive food structures and compositions, Etienne's Traite de l'office was the most complete work on the subjects in which it specialized: hors d'oeuvres, salads, fruit dishes, and especially, desserts. Etienne was responsible for creating the large formal banquets and impressive presentations required by his position as chef for the French ambassador to England, and his recipes reflect this experience. But his book–and similar works published by other professional chefs–chronicle the era’s increasingly complex and elevated tastes in food, and the fashion for meticulous attention to artistic presentation.

French Chefs Arrive in America

From the early 19th century, New Orleans has enjoyed a reputation as one of the best restaurant cities in the country. The French colonial past of the region shaped its food culture, as did the importation of many chefs who sought work in America after the French Revolution. Long before the rest of America discovered the pleasures of French food, New Orleans offered a sophisticated cuisine not found anywhere else in the country.

A Guide for the English & American Tourist

Early handbooks directing tourists to the finest eateries of Paris testify to the internationally recognized status of French food. This book passes over Paris’s history and art treasures to focus on its restaurants. As the author wryly points out in the introduction, "Paris, needless to say, has her profoundly serious side of life, her miseries, and tragedies; but to dwell upon these is not an aid to digestion."