Evolution of the Book

Printing clearly revolutionized European literary culture, yet in some cases, the printing press simply accelerated developments that were already in motion within the manuscript culture of Europe during the late Middle Ages. Among such developments was the increasing use of alphabetization and indexing to help readers find desired information within a manuscript. Also important was the growing availability of paper, which had the effect of deprofessionalizing manuscript production, making writing surfaces affordable for scholars who could consequently serve as their own scribes. Individuals could use paper to keep notebooks, where they might jot key ideas from important texts rather than laboriously transcribe the entire text. A result of these trends was that cursive script became popular and writing styles proliferated, as each individual writer’s idiosyncrasies came to the fore, unrestrained by the professional standards of a guild.

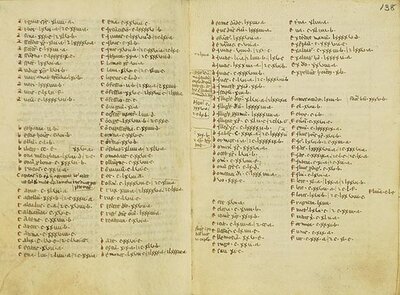

Name Indexing

An innovative feature of later medieval Bibles was an index of Hebrew names, such as the alphabetical list seen at the end of this 13th-century English Bible. Although alphabetical organization of literary subject matter seems basic to us, its practice developed slowly during the Middle Ages and was taken for granted only after the advent of printing.

Gift of William G. Mennen.

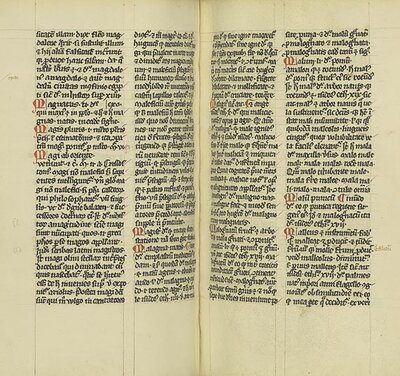

Subject Indexing

The printed book encouraged indexing because the contents of each copy of a given edition were largely fixed. In contrast, every manuscript of a given work was unique: the pages of one manuscript did not correspond precisely to those of another because they lacked the standardization that mechanical reproduction imposed. Scribes generally did not even number their pages. Consequently, finding information on a given subject required skimming the entire manuscript. Frustration with this procedure is reflected in this index to a collection of sermons, which presents subject headings arranged in alphabetical order. The Roman numerals that follow refer to the numbers of the sermons. The utility of such an index is obvious; it enabled a preacher to locate treatments of his subject matter quickly. Since only texts with stable numerical elements could be indexed, it was not until page numbering became standard practice that indexes could become a regular feature of books.

Obtained in 1897 for A. D. White.

Glossaries

Medieval university scholars tried to ease the burden of learning by devising reference works, such as this alphabetical glossary of words used in the Bible. The impulse behind such efforts eventually gave rise to dictionaries.

Obtained in 1893 for A. D. White.

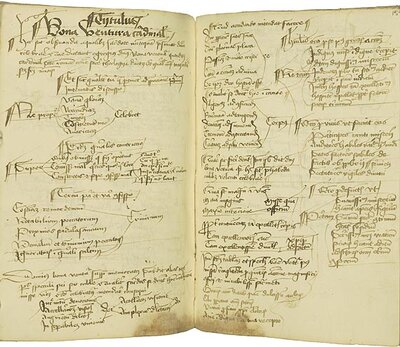

Taking Notes

These pages of a paper manuscript show a scholar’s notes on a text by the 13th-century cardinal, St. Bonaventure, arranged in outline form. The script is difficult to read because it was written hastily for private use, without any intention of meeting professional standards. Cursive script quickly emerged as the natural form of personal writing, as it remains today.

Obtained in 1897 for A. D. White.

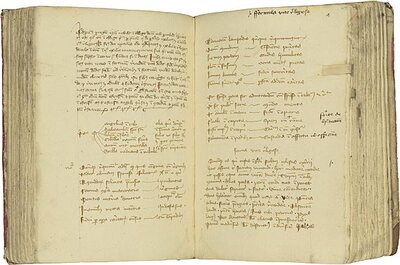

Chapter and Verse

This notebook has tabs made of parchment strips to indicate where separate texts begin. The leaves in the second half of the book have also been numbered, and an impromptu table of contents or index in the front indicates the folios where subjects and titles can be found. The page on the right shows the Arabic numeral 7 in the top margin, indicating the folio; the numeral looks rather like the Greek character lambda (l), but is an early form of the number 7. (The number 69, penciled into the corner, is a recent addition that indicates the number of the folio from the beginning of the book.) Such features, appearing in a manuscript that was produced a hundred years before printing, suggest that the impulse to organize text for easier reference was already keenly felt. Printing was wonderfully suited to satisfy that impulse.