How the Classics Survived

The main problem of literary production in a manuscript culture was distortion of the text by weary or careless scribes who introduced errors at successive stages of copying. Modern scholars strive to recover the most complete or earliest version of a text by comparing all the manuscripts of a given work and analyzing differences between them.

Another complexity of textual transmission via manuscript was the tendency for works to be misattributed. The work on display here, known as the Rhetorica ad Herennium or De ratione dicendi (its actual title has been lost), was written in the first century B.C. At some juncture before the fourth century A.D. it was misattributed to the great orator Cicero, and this false attribution held for a thousand years. In the 15th century Renaissance humanists proved, on the basis of linguistic principles, that Cicero could not have been its author. Yet even after the connection to Cicero had been disproved, the manual’s long tradition compelled printers to publish it among Cicero’s works.

These books represent various stages in the preservation and reiteration of a classical text: medieval manuscript, early printed editions, and modern critical editions with apparatus and translation.

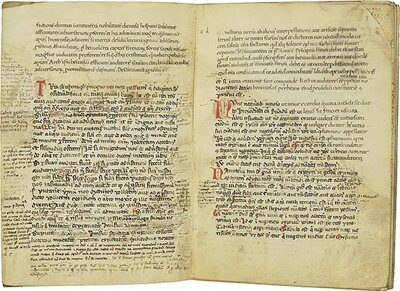

Cicero, 14th Century

Manuscripts, frequently passed down for several generations, can preserve archeological layers that reveal the experiences of their former owners. This exemplar of the Rhetorica ad Herennium testifies to its importance among medieval and Renaissance readers alike. The parchment leaves have been torn and repaired: below the tear, on the older parchment, a late Gothic hand of the 14th century is preserved; above the tear, on the newer parchment, a humanistic hand of the 15th century appears. The interlinear and marginal comments, or "glosses," in the older portion of the book reveal how carefully the text was read by successive owners, and the effort made by a later owner to restore the mutilated text likewise indicates how keenly it continued to be valued.

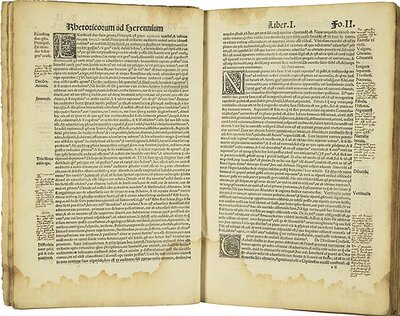

Cicero. France, 1522

This French edition printed in 1522 mimics the appearance of medieval manuscripts. Words are heavily abbreviated and there is little differentiation among the sections of the work– initials, marginal headers, and capitalized words, rather than paragraph breaks, perform this function. A reader has underlined passages in the text and has added marginal comments in order to introduce additional divisions into the solid mass of print.

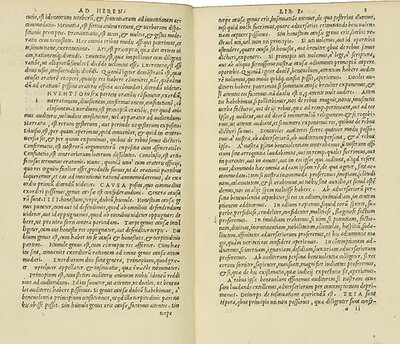

Cicero. Italy, 1521

The Venetian printer Aldus Manutius (ca. 1452–1515) raised the standards of bookmaking and had a keen sense of what the reading public wanted. He strove to secure the best manuscripts for his editions, and he introduced portable copies in elegant humanistic fonts for the reader’s convenience and pleasure. The family business continued the tradition after his death, as is seen in this edition of Cicero’s rhetorical works, published by Aldus’s father-in-law, Andreas Torresani. In this edition, abbreviations are scarce; while they were useful for overworked scribes, they were no longer necessary when a book could be reproduced in a printing press. The clear Roman font and lack of abbreviation show how, by the first decades of the 16th century, printing was evolving beyond the manuscript model and transforming the appearance of the written word.

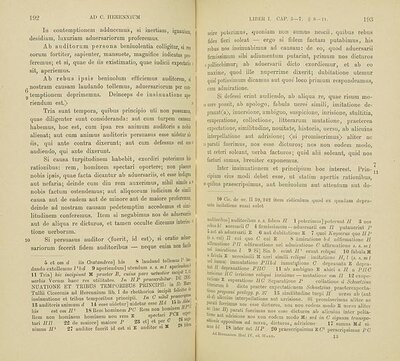

Cicero, 1894

This 1894 critical edition was made by comparing the best surviving manuscripts of the text. The editor supplies variant readings at the bottom of each page. In addition to the painstaking care he has taken to restore the text to its original version, the editor has imposed paragraph divisions and numerical distinctions to make it easier to read and reference.

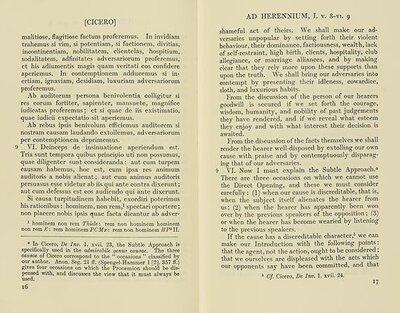

Cicero. Ithaca, NY

This edition, which stands at the head of the Loeb Classical Library’s collection of Cicero’s works, was prepared by Harry Caplan (1896–1980) After receiving his B.A., M.A., and Ph.D. from Cornell, Caplan taught in the Classics Department, serving as its chairman for 17 years, from 1929 to 1946.

This edition, created for 20th century students of Latin, has been supplied with a facing-page translation to make it more accessible. Only the more significant variant readings have been provided; these appear immediately beneath the Latin text. The editor has also added footnotes to the translation for additional guidance. Notice that the Loeb edition disagrees with the critical edition about where to divide the paragraphs; such decisions are subject to the editor’s judgment.