Manuscripts in the Age of Print

When Gutenberg invented moveable metal type in the 1450s, he chose to print the most important book in Christendom in order to introduce his fledgling technology to the market. While he was a mechanical genius, his ability as a businessman was nothing extraordinary, and he eventually had to surrender his assets to pay his debts. In the hands of the entrepreneurs who followed, however, printing quickly established itself as a viable means of supplying the demand for books–and eventually as the only way. Soon, printers surpassed scribes in the marketplace by reproducing the familiar look of the manuscript in a fraction of the time and at lower cost. By the end of the 16th century, professional manuscript-copying dropped off precipitously. It was later done only under certain circumstances, such as in locations where printing presses were rare, or on occasions that required the pomp that only calligraphy on fine parchment could supply.

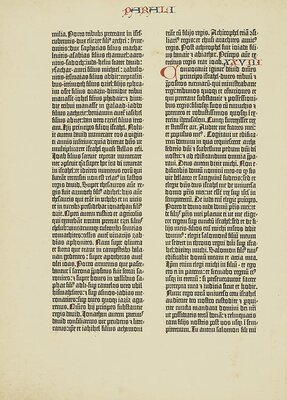

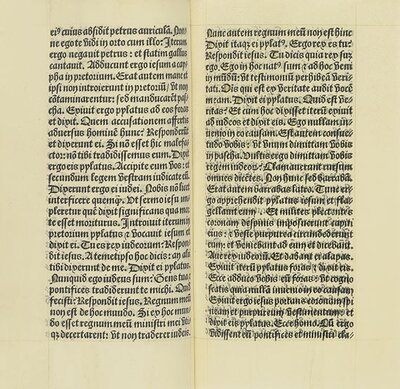

Gutenberg’s Bible

This leaf, from the famous edition of the Latin Vulgate known as the Gutenberg Bible, displays the first printer’s attempt to reproduce the look of the medieval manuscript. The type is based on the Gothic minuscule of the High Middle Ages and preserves the scribal abbreviations found in manuscript books. An important difference, however, is that the impressions are made on paper rather than parchment. This alternative writing surface had been making headway for some time in Europe, but only with the advent of the printing press did paper become the dominant writing surface.

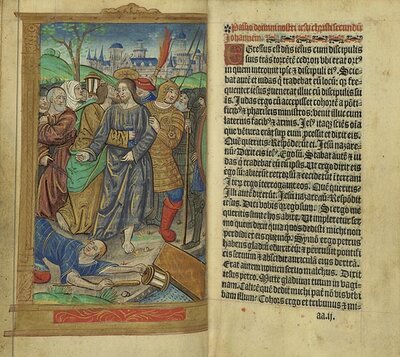

Illuminated Print

Since Books of Hours were bestsellers before the advent of printing, it was natural that early printer-publishers should try to find a niche within this high-demand market. The artists who supplied the illuminations for the handwritten Books of Hours were perfectly willing to do the same for printed versions of the popular prayerbooks. This Book of Hours, printed on fine parchment, strives to imitate the familiar work of the scribes.

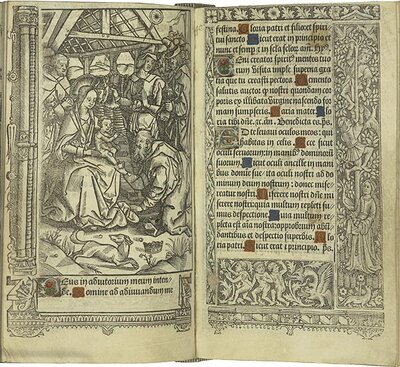

Woodcut Illustrations

The origins of printing are obscure, and it has sometimes been supposed that the late 14th-century development of woodcuts, which could supply illustrations more quickly and cost-effectively, provided the inspiration for reproducing words mechanically as well. This Book of Hours shows the fusion of mechanical means of reproduction for both image and text. The colored and highlighted initials, however, were supplied by professionals known as rubricators, who had performed this service throughout the Middle Ages.

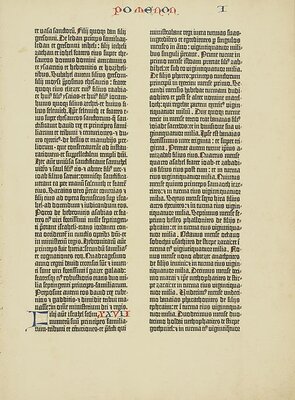

Printing on Parchment

One of the drawbacks of printing on parchment arose from the inconsistent quality of the animal-hides used to make it. Hides were not entirely opaque; thus a given page sometimes had translucent patches where the text on the other side showed through, making some of the words difficult to read, as in this printed Book of Hours. The problem did not occur with paper, which offered a consistently opaque surface.

Charter of Nobility

Even as late as the 17th century, certain texts recommended themselves to the craftsmanship of scribes rather than the machines of the printers. This Spanish charter of nobility, lavishly crafted in 1636, was too dignified a text to entrust to mechanical means of production. Furthermore, it was bestowed too seldom to justify mass production. Thus, even more than a hundred years after the close of the Middle Ages, the skill of scribes and illuminators came together to produce this marvelous book at the command of the Spanish king. His seal of office, impressed upon the leaden pendant, validates the charter.

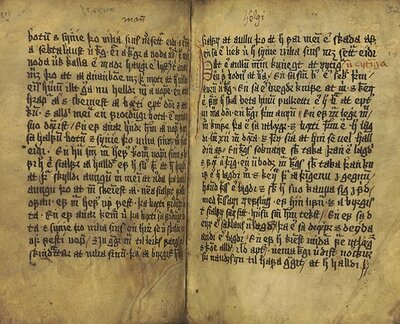

Icelandic Jónsbók

Printing and paper came relatively late to Iceland, home of the medieval sagas, on the periphery of northwestern Europe. Although a printing press was active on the island for a few years during the 1530s, demand for legal and other documents occupied copyists using medieval scripts and rubrication on domestically produced parchment. Thus despite its late date (ca. 1550, around the time of the Lutheran Reformation in Iceland), this copy of Jónsbók--Iceland’s law code, in force from the late 13th through the end of the 17th century--is essentially a medieval manuscript.