Noting Sound

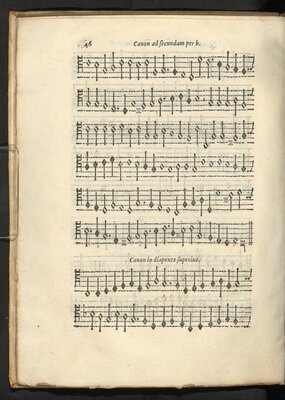

Although musical notation is the most common means of representing sound on the page, a variety of techniques have been used to document and describe sound. Like stories told in the oral tradition, early songs were learned by ear. Medieval European religious communities, who performed the same songs at regular intervals as part of their religious life, sought to devise musical notation so that the songs could be preserved and performed consistently. But while the printing of text from movable metal type fueled the “printing revolution,” mechanical reproduction of music was more difficult and took longer to perfect. Shown here is a 1578 example of printed music using a staff and musical notes. At the same time that printers were learning to print music, other craftsmen of the early modern period created more musical instruments and standardized their production.

Giovanni Padovani. Ioannis Padvanii Veronesis Institutiones ad diuersas ex plumurium ouvum hamonia cantilenas. Veronae: Apud Sebastianum & Ioannem fratres a Donnis, 1578.

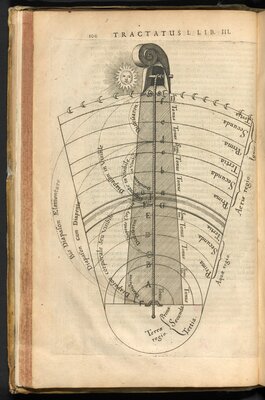

Robert Fludd. Utriusque cosmi majoris scilicet et minoris metaphysic. Francofurti: Prostat in officinal Bryana, 1626.

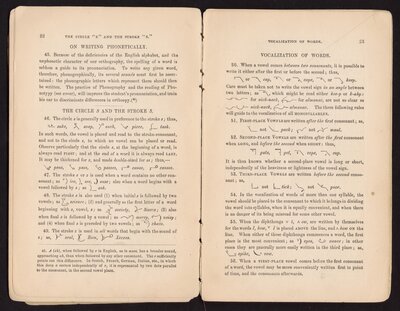

Other printed works documenting sound appeared in fields ranging from linguistics to more practically oriented systems such as “phonography.” Based on the idea that one could create short signals to stand in for syllables to speed the writing of spoken words, phonography led in turn to the concept of shorthand and faster dictation.

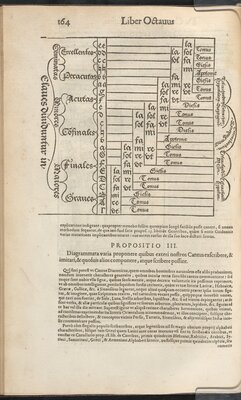

As technology changed, so did public attitudes towards those who could not hear or see, spurring the development of alternative communication systems to aid the blind or deaf. Shown here is a system of numerical musical notation, used in teaching the blind to understand individual music notes and their corresponding sounds.