Portability and Distribution: Putting Print (and Sound) to Work

With Johann Gutenberg’s invention of the type mold and moveable metal type in the 1450s, books became more accessible and affordable. This shift can be seen even in the early decades of printing, as the western world moved from handwritten manuscripts to printed books. One example was the production and ownership of Books of Hours. These small Christiandevotional guides were enormously popular in the 14thand 15thcenturies, but were costly to produce, as they were typically written on fine vellum and often exquisitely illuminated using materials such as gold leaf. From the second half of the 1400s, however, Books of Hours could be more quickly produced with the printing press, making them less expensive and allowing a wider range of people to own such a work. Some printed Books of Hours were enhanced with hand decorations to make the volume appear to be a more expensive, custom-made work.

Les p[r]esentes heures a lusage de Rouen sont au long sans Rie[n]s requerit auecq[ue]s les heures de la co[n]caption et plusiers aultres suffrages neuuelleme[n]t . Paris: pour Jeha[n] Curges, Pierres Huuin [et] Jacques Cousin, [1503].

The use of small (and ephemeral) pamphlets and broadsides in the early modern period is well-documented, and examples can be seen here, with a Reformation-era pamphlet by Martin Luther’s follower Philip Melanchthon.

Print could also be used to appeal to the reader’s emotions; two examples in this case show how the abolitionist movement did so. The iconic broadside depicting the slave ship Brookes was famously used to advance anti-slavery goals in both Britain and the United States. The terrible image of humans crowded and restrained in a slave ship shone a light on the horrors of human enslavement, and the broadside’s wide distribution advanced the abolitionist cause.

Broadside depicting the slave ship Brookes. Philadelphia, 1808. Gail and Stephen Rudin Slavery Collection, 4681.

Before they could widely distribute sound to appeal to the emotions, authors could describe it as seen in the pamphlet, “Flogging of Women in Jamaica.” This pamphlet is an example of aural description identified by historian Marisa J. Fuentes in which a (white, male) author describes the torture of enslaved women in terms of physical violence as well as the aural effects of this violence on both the women and witnesses, and by extension, readers. Activists today continue to use printed formats to promote their causes. Today, however, they also have access to sound recordings to highlight specific incidents. Perhaps one of the most recent uses of sound for affective persuasion involves playing the recorded sounds of immigrant children who were separated from their parents at the U.S. border in 2018.

Flogging of Women in Jamaica. London: British and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society, 18--. Samuel May Anti-Slavery Collection.

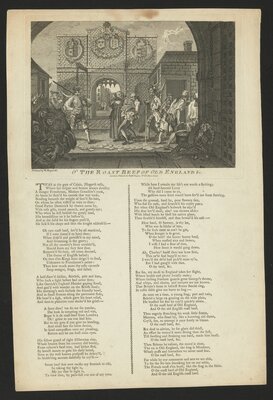

Popular ballads often served political purposes, sometimes overt and sometimes oblique, as seen in the 18th-century broadside containing lyrics highlighting the political differences between England and France and illustrated by Hogarth. Hundreds of years later, the practice of distributing visual material open to interpretation by a canny reader continues in the form of sticker art, which makes use of any available sticker format, often commandeering stickers designed for other purposes.

Theodosius Forrest, O’ The Roast Beef of Old England, &c. Illus. William Hogarth. London: R. Sayer, [1752?].

![Les p[r]esentes heures a lusage de Rouen...](https://exhibits.library.cornell.edu/images/14220-f1f721bb498e443b00091dc3a9337381/full/!400,400/0/default.jpg)