The Handheld Book: or, Every Book Its Reader

As advances in printing technologies made book production cheaper and ownership more affordable, reading became a more private practice. Just as sound devices became smaller, the ability to produce very small books encouraged portable texts that served a wide variety of purposes. In some situations the need for portability was practical: travel guides best served their user if they could be carried and consulted easily during travel, and the user could consult a professional guide while out on a job. A variation on the travel guide – the country guide written for U.S. military personnel deploying overseas – was also printed in a pocket format for easy transport and use.

United States. Army Services Force. Information and Education Division. Pocket Guide to Germany. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Govt. Prin. Off., 1944.

Yet other works’ small size could be due to the reader’s desire for discretion or privacy. Items such as early travel guides written specifically for gay travelers navigating an unknown city show how a small guidebook could provide safety for its reader by discreetly identifying gay-friendly hotels, neighborhoods, and establishments.

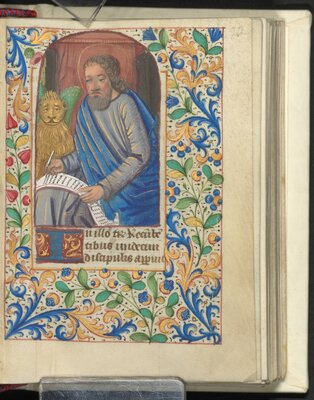

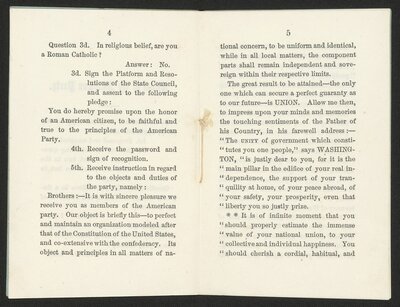

In some cases readers desired both portability and discretion. The so-called Tijuana Bible, a format that appeared in the 1920s and refers to a small booklet containing tiny, pornographic cartoons, could easily be carried around and consulted in the palm of one’s hand. In quite a different form of devotion, prayer books were also frequently created in small, pocket-sized versions easily carried on one’s person, encouraging personal piety by making devotional consultation possible throughout the day. Secret societies, such as the American Party (more commonly known as the “Know-Nothing Party”), used items such as this small pamphlet with a blank cover to contain its swearing-in questions and commitments. This nineteenth-century American political group was anti-immigrant and anti-Catholic. Aspiring members were supposed to answer questions indicating that they believed in God, were old enough to serve in the military, and were not Catholic.

Ima Pushover presents: Betty Boop in “Improvising.” United States: s.n., ca. 1920-1940. Tijuana Bibles Collection.

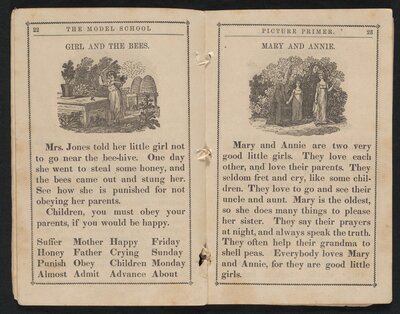

Finally, works for children often are printed in a small format, as shown in this selection of historical examples. From Sunday School literature to textbooks to a book of children’s amusements, the compact size was meant to be well suited for the smaller hands of the youngest readers.

“The History of John Robins, the sailor.” The Child’s Library, v. 8. Philadelphia: The American Sunday-School Union, 1825.

![The English Physitian [sic] enlarged](https://exhibits.library.cornell.edu/images/14227-799cb877e2e912f98f4b11ca6418de6b/full/!400,400/0/default.jpg)