Continuing Encounters

English and French accounts of their impressions of Native Americans largely echo those written by Spaniards. European writers, whose descriptions of America circulated widely across the Atlantic, stressed the Indian exotic, contrasting native dress, language, and social life with their own. Even those accounts that viewed Native Americans sympathetically doubted the compatibility of native and European cultures.

Initial encounters, often characterized by courtesy and curiosity, quickly gave way to friction and hostility. Europeans sought and claimed American resources, especially the precious metals discovered in the Spanish colonies. In North America, land, timber, and furs substituted for gold and silver. Growing European communities and their demands for resources profoundly affected native societies. Many Indians perished after contracting diseases to which they had no inherited resistance. Others died in armed attempts to expel European interlopers. European contact often pitted Native Americans against each other in a scramble for resources and survival. Increasingly, Indians left their traditional lands to reestablish themselves further west, or to ally themselves with other native people. In the 18th century, Native Americans became partisans in the French and English struggle for hegemony in North America, and later in the Revolutionary War.

Robert Beverley. The History and Present State of Virginia, in Four Parts. London: R. Parker, 1705.

Beverley, a plantation owner, carefully recorded his detailed observations of the customs of the Indians who lived near the James River in Virginia. In his time, more than 100 years since the first white settlement in the area, the native presence was greatly diminished. Beverley provides insight into the roles of women, religion, apparel, agriculture, and other areas of Indian society that would soon be irrevocably altered. Part iii of this book, which also covers the political and natural history of Virginia and its government, is devoted to “The Native Indians.” It is illustrated with engravings signed by Simon Gribelin, who adapted the 1590 de Bry engravings in Thomas Hariot’s Virginia.

Amédée Franois Frézier. Relation du Voyage de la Mer du Sud aux Côtes du Chily et du Perou Fait Pendant Les Annes 1712, 1713 & 1714. Paris: Chez Jean-Geoffroy Nyon, Etienne Ganeau, Jacque Quillau, 1716.

Frézier, a French engineer, was commissioned by the King of Spain to assess the coastal fortifications of Peru and Chile. His voyage touched the east coast of South America, rounded Cape Horn, and sailed as far north as Lima’s port, Callao. Frézier’s detailed maps and charts provided critical information for future navigators. His drawings and descriptions of Peruvian and Chilean life are equally valuable for their ethnographic and historical details. Frézier copied this illustration of Incan royalty from the first of twelve drawings he saw of Incan leaders made by the Indians of Cuzco. Nicholas Guerard produced the engravings for this edition and the English edition published a year later.

Louis Hennepin. A New Discovery of a Vast Country in America, Extending Above Four Thousand Miles. London: M. Bentley, J. Tonson, H. Bonwick, T. Goodwin, and S. Manship, 1698.

Hennepin, a Flemish Franciscan friar, sailed to New France in 1675 and spent the next three years working among the Iroquois as a missionary. He then accompanied René-Robert, Sieur de la Salle on his exploration of the Great Lakes and the American Midwest. While searching for the headwaters of the Mississippi River in Minnesota, Hennepin and two others were captured by a group of eastern Sioux and held for nine months.

He returned to France in 1681 and published the first account of his adventures, Description de la Louisiane, in 1683. This book and Nouvelle Découverte d’un tres grand pays, published in 1697, were immensely popular, providing the public with an insider’s view of Indian groups as diverse as the Iroquois and the Sioux. Critics note that Hennepin exaggerated many of his accomplishments.

The fanciful frontispiece shown above, in the first English edition of Nouvelle Découverte, incorporates many items associated with native groups across North America.

John Rodgers Jewitt. Narrative of the Adventures and Sufferings of John R. Jewitt. Middletown, Connecticut: S. Richards, 1815.

Jewitt, a young English blacksmith, was captured in March 1803 when the fur-trading brigantine Boston, moored in Nootka Sound on the west coast of Vancouver Island, was attacked by men led by Maquinna from the village of Yuquot. Angered by a perceived insult, and frustrated by the ill-treatment they had long received from European traders, the villagers killed all but two of the crew. In return for his life, Jewitt agreed to be Maquinna’s slave and to forge daggers, knives, and other implements for his people.

Jewitt’s Narrative is rich in ethnographic detail about village life along Nootka Sound. His account also shows the disdain he felt towards his captors. Captivity literature, which emphasized adventurous hardship endured by innocent captives, was extremely popular in the seventeenth through the nineteenth centuries. Jewitt’s work is still in print.

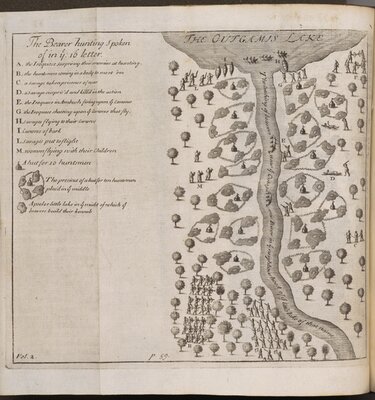

Louis Armand de Lom d’Arce, Baron de Lahontan. New Voyages to North-America. London: H. Bonwicke, 1703.

Lahontan was a French military officer who served in Canada from 1683 to 1692, spending much of his time in the area of Lake Ontario. Familiar with the Iroquois, he also led an expedition to the upper Mississippi, by way of the Wisconsin River, ending up in Minnesota. His admiration for the Iroquois and other groups helped to counter the image of Native Americans expounded by French missionaries and others. While his work has been criticized as fanciful, Armand’s account of the simple delights of life in the wilderness was very influential in the subsequent growth of primitivism in France and England. The plate shown here shows the important role the beaver played in French-Indian interactions.

John H. Allan. Letter to the Maine Indians, May 1780.

Colonel John Allan was appointed superintendent of the eastern Indians by the new American government in 1777. During the Revolutionary War he tried valiantly to keep the Indians of Maine, the Passamaquoddys, Penobscots, Micmacs (Mi’kmaq), and others, allied with the American cause. In this letter, accompanied by the presentation of wampum strings, he formally requests their presence at a council to be held at Passamaquoddy in May 1780. Many of Allan’s efforts were in vain. In July of that year, all but about a hundred Indians, mostly women and children, set off for British territory. While many eventually returned, others remained loyal to the British crown.

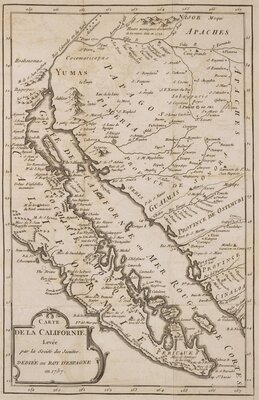

Miguel Venegas. Histoire naturelle et civile de la Californie. Paris: Durand, 1767.

Venegas, a Mexican Jesuit whose order had been involved in missionary efforts in California for fifty years, was assigned the task of creating a general history of that area in the 1720s. For this project he was given access to Jesuit and secular documentation rich in details about California’s native peoples. He completed his work, “Empresas Apostólicas,” in 1739. However, it was not published until 1757, and then in a condensed version, as Noticia de la California. This French edition of his work contains Father Eusebius Francis Kino’s 1702 map, which shows that California was not an island, as some had contended.