Sideshow to Powwow

Europeans quickly grasped the value of Native Americans as entertainers. George Catlin often brought “real” Indians to pose alongside his gallery of portraits in the 1830s and 1840s. Groups of Iowas and Ojibwas joined him in Europe, demonstrating archery, ball play, and dancing. Catlin exhibited his portraits of Native Americans throughout Europe and America, often lecturing about the diversity of native cultures, and about the negative effects of unbridled American territorial expansion on Indiana lands and communities.

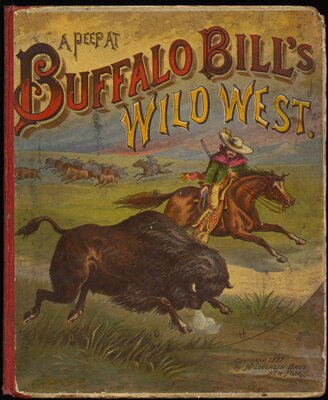

Troupes of native performers were on the road when William F. “Buffalo Bill” Cody started his popular Wild West shows in the 1883. Cody, a showman, capitalized on the dramatic potential of portraying “authentic” events he had witnessed. Indians were employed to enact their part in “history” as interpreted by Cody. Arguments that he was exploiting native show members and glorifying warfare started almost immediately, and continue today.

Confined to reservations in the late 1800s, Native Americans reaffirmed their cultural identities together through music and dance. Local powwows began in Plains communities as secular dances. Today, powwows and other gatherings, powerful public affirmations of Indian identity, are conducted throughout North America for appreciative native and non-native audiences.

Buffalo Bill’s Wild West: America’s National Entertainment Led by the Famed Scout and Guide Buffalo Bill. Hartford, Conn, 1885.

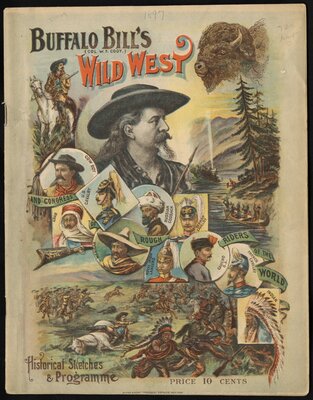

William F. Cody (1846-1917) had a varied career before launching Buffalo Bill’s Wild West in 1884. After fighting with the Union Army against the Confederacy, he moved to Kansas, where he provisioned railroad crews by shooting buffaloes. He also served as a scout and guide, fighting in as many as sixteen skirmishes with Native Americans. His exploits were publicized in dime novels and plays. From 1872 to 1883, he played himself in many dramas about the “Wild West.”

Buffalo Bill’s Wild West shows consisted of a series of elaborately reenacted “historical” scenes, interspersed with feats of sharp shooting, rodeo-style events, and races. Native Americans figured prominently, with Buffalo Bill riding in to save the day.

Buffalo Bill’s Wild West and Congress of Rough Riders of the World: Historic Sketches and Programme. New York: Fless & Ridge Printing Co., 1897.

Sitting Bull’s Autograph

Sitting Bull (1834-1890), traveled with Buffalo Bill’s Wild West show in 1885. Audience members, who remembered his role in Custer’s ignominious defeat at the Little Big Horn, often booed his entrances. Part of Sitting Bull’s contract with Cody allowed him to sell his autographs.

Joseph Elam Stimson. Souvenir of Cheyenne Frontier Show, 1896-1902. Brooklyn, New York, 1902.

Native Americans have been part of Cheyenne Frontier Days, a popular Wyoming rodeo, since 1898 when Buffalo Bill’s entire troupe participated in its parade. Then, as now, visiting Indians performed dances for enthusiastic audiences. The Indian Village at Frontier Park, at first an informal area where Native Americans were encamped for the event, is always a popular attraction. Today, food vendors and booths selling native arts are the backdrop for native performances. Stimson, a local photographer, was noted for his pictures of the town of Cheyenne in its early years.

George Catlin. Catlin’s Indian Gallery. Handbills and Admission Tickets. London, June 1840.

Catlin (1796-1852) was determined to educate the public about the diverse and threatened native cultures he encountered during his 1832-1836 tours of the West. Catlin’s well-publicized Indian Gallery, which traveled to several cities in Europe and America, featured his paintings of Indian subjects and his collection of ethnographic objects as background to his lectures. Catlin’s admiration for native peoples and his criticism of incursions into their territories provided audiences with a different perspective about western tribes. In late 1839 he shipped eight tons of materials to London, where his gallery opened in January 1840. The gallery traveled to various venues until, in 1852, declining public interest forced his to auction off his paintings to satisfy creditors.

Catlin was a born publicist. Cornell’s Native American Collection includes handbills, admission tickets, and newspaper clippings advertising his gallery in London and Paris.

Poster. Inter-tribal Indian Ceremonial. Gallup, New Mexico. August, 1934.

The Gallup Intertribal Ceremonial, one of the oldest continuously operating intertribal gatherings, began in 1922 in an open lot in Gallup, which adjoins the Navajo Reservation. Today, individuals from over 100 tribes nationwide participate in its popular juried art and dance competitions held every August in Red Rock State Park.

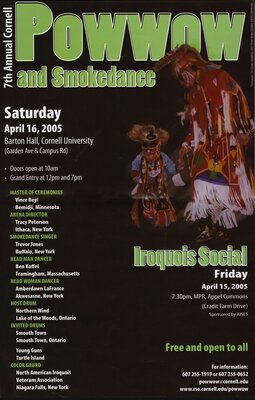

Poster. Seventh Annual Cornell University Powwow and Smokedance. Ithaca, New York, 2005.

Powwows today are strong public demonstrations of Native American identity. Dancing together, Indians celebrate their individual tribal heritages, and commonalities with other native groups. While the origin of the powwow as a social gathering lies in the Plains, today they are held in nearly every major city in the United States and Canada, and in small communities throughout. Powwow music centers around several drummers, seated around a large drum, who lead the songs accompanied by men and women standing behind them. The dancers’ attire is usually determined by the type of dances performed. Powwows today often feature dance competitions with prizes for the winners. Men compete in Traditional, Grass, and Fancy dances, while women dance Jingle, Shawl, and Traditional dances.

The American Indian Program at Cornell University celebrates its 8th Annual Cornell Powwow and Smokedance in April 2006.