Botany as a Hobby

During the Victorian era, women - especially middle and upper class women - were broadly pushed away from business, science, finance, and higher education and were expected to devote their time to “more delicate pursuits” like raising children and beautifying the home. For a number of reasons, botany and the growing of plants became a serious hobby for vast numbers of women throughout the 19th century in Britain and America.

There were few ways in which an inquisitive-minded woman could expand her learning at the time without either outstanding luck, substantial fortune, or both. But as the middle class grew and more women were in positions where they had idle time (a luxury seldom, if ever, afforded women of the working class) they wanted things to occupy their minds and hands. Botany happened to be a perfect fit - it fit well with the Romantic notions of Nature’s importance but didn't necessitate rutting like breeding animals did; polite Victorian society was loathe to discuss anything sexual in an overt manner. Flowers provided an undeniable spark of beauty both inside and outside the home, and a well-tended garden not only satisfied the family but also caught the notice of the neighbors.

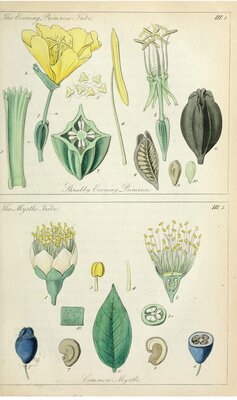

The botanical hobby developed its own literature, of which the language of flowers was an important subset. Numerous books and magazines were printed with an eye towards the home horticulturist; publications like Benjamin Maund’s The Botanic Garden and Edwards’s Botanical Register (which ran for more than 17 years) helped fuel Victorian botany with gardening advice, plant identification, and often excellent illustrations.

Floriography books themselves were almost omnipresent from 1820 to 1870 when most families would have had at least one, whether ornate works suitable for a sitting room table or slim, pocket-sized volumes for personal reference. They would be kept in the parlor or taken with on picnics, or possibly as bedroom reading. Interest in floriography was seen as a sign of gentility, and the books would often be given as gifts to women, girls, and even young boys.