History

Floriography – sending messages with flowers – is an ancient art, rooted in the symbolism of China, Egypt, and Assyria. The 18th and 19th century floriographic systems in Europe are often attributed to stemming from a Turkish origin, but what existed in Turkey used many more items than flowers and was more of a mnemonic for pieces of specific poems (as described in Dr. Brent Elliott’s research with the Royal Horticultural Society). Much of what became the British tradition began in France– 17 volumes in Mann Library’s Language of Flowers Collection are in French – which had been the center of European floral fashion since the eighteenth century.

As the fashion for the language of flowers grew, the books became more complex and began to include poetry, etymology, and horticultural information. Authors striving for a new angle linked flowers with classical mythology, folklore, heraldry, fortune-telling, and birthdays as well as themes of morality. Illustrations ranged from delicate to lavish. Often, language of flowers books were intended as gifts and can usually be identified by their sentimental illustrations and bindings, as well as the dedications handwritten on their opening pages. Indeed, during the nineteenth century, floral dictionaries became standard equipment in the middle-class home. They were displayed in the parlor, taken out to the garden, and kept in the bedroom. Like flowers and flower gardens themselves, they demonstrated the gentility and moral virtue of the women in a household.

The historical, social and intellectual context of the Victorian era explains the widespread popularity of language of flowers books. The language of flowers fashion was centered in the large and newly prosperous middle classes in Britain, France and the U.S. fostered by the Industrial Revolution. Women in these households had servants and leisure-time, but few occupational outlets. In keeping with the Victorian ideal of self-improvement, flower gardens and horticulture were seen as a constructive pastime. Cut flowers were important in interior decoration and were worn as personal ornament more often than they are worn today. Flowers were significant in literature — such poets as Wordsworth had previously popularized the Romantic view of Nature as inspiration. By Victorian times, sentiment had become fashionable for its own sake, and collecting language of flowers books became a trendy pastime. The language of flowers also offered an acceptable medium for women to participate in the shaping of cultural values. Largely barred from airing public opinions on moral issues in the mainstream press, educated Victorian women found in the language of flowers the possibility for public commentary as compilers of poetry and essays that expounded on human virtues and vices.

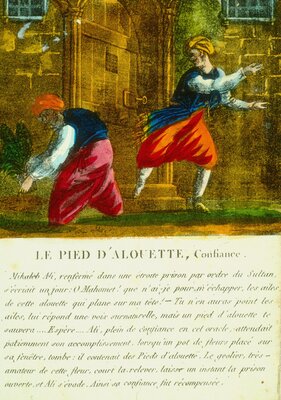

All fashions are destined to wane. By the later nineteenth century, the language of flowers gave rise to parody. It was satirized in several articles in Punch and the book by French caricaturist J. J. Grandville Fleurs animées, with its comic drawings and the story of a tryst gone awry when wrong flower was sent as an invitation. In the later years, the beautiful hand-colored prints in the earlier books were typically replaced by garish lithographs in an effort to lower the costs of production. The many variations of these books are fascinating, however, for those who seek to understand nineteenth century fashions and culture, as well as for those who enjoy flowers and their illustrations in books.