A Ship for Science

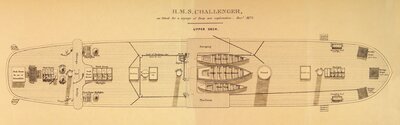

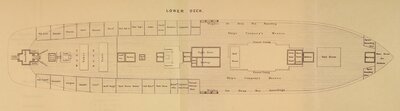

HMS Challenger began her career as a ship of the line, a three-masted corvette in service of the Royal Navy. With the advent of ironclad ships in the 1860s she became obsolete as a warship and was retrofitted as a science vessel. All but two of her seventeen guns were removed, her spars were trimmed, laboratories were added, and a dredging platform was fitted to suit her new-found purpose. Not large even for her day, Challenger was 200 feet long and a mere 40 feet in width. A coal-fired steam engine served to keep her on station during soundings.

When Challenger left Portsmouth she carried 21 officers and 216 enlisted seamen, in addition to the scientific crew; by the time she returned in May of 1876 only 144 crew remained, losing some to death, illness, and planned departure but the majority due to desertion – a common occurrence amongst young sailors stuck aboard a small vessel making port in exotic locales.

The scientists aboard Challenger were directed by Charles Wyville Thomson, later knighted for his efforts on the voyage, who had made discoveries in the late 1860s indicating deep oceanic circulation. He led the "scientifics" as they were known, including naturalist John Murray (often known as the father of oceanography), Scottish chemist John Young Buchanan, naturalist Henry Nottidge Mosely, and Rudolf von Wilmoes-Suhm, who became known fro his work on crustaceans during the expedition. All of them would go on to notable careers in European universities.