Bitter is Better: Cider Apples

Cider apples do not conform to the standards that most Americans consider when thinking about apples – factors such as size, crispness, and color are largely irrelevant to the quality of cider that a given apple will produce.

What makes a cider apple?

There are three primary characteristics that determine how an apple will be used in the cider making process: sweetness, or the quantity of sugar present; sharpness, or how acidic it is; and bitterness, the presence of compounds known as tannins which produce astringent and bitter, “mouth puckering” flavors. The ratios between sugar, acid, and tannin form the basis for the broad categories by which apples are grouped – sweets, sharps, bitters, bittersweets, and bittersharps. While a sweet apple might be the perfect thing for a pie or sliced with cheese, it is the bitter tannins that create a complex, enjoyable alcoholic beverage.

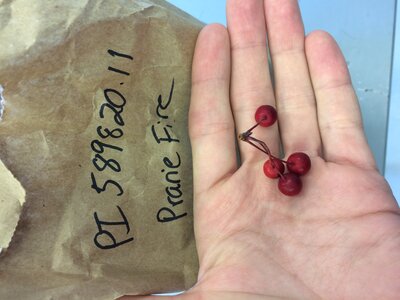

As can be seen in the apple cultivars shown here, the appearance of a cider apple is often not what we, as consumers, would consider a “good apple”. These photographs show cider apple varieties being grown at the Cornell University Agricultural Experiment Station research orchard in Ithaca, NY and the United States Department of Agriculture-Agricultural Research Service’s apple germplasm repository in Geneva, NY. The “PI” numbers that can be seen with the apples on the right are assigned by the USDA to identify accessions in their collection of more than 3,000 unique apple genotypes.

Apple trees are an example of extreme heterozygotes; that is, when grown from seed an apple tree won’t have the same characteristics as its parent trees but instead will differ, often radically. To preserve specific traits, apples are propagated asexually – by grafting.

The grafting process takes cuttings from existing trees and attaches them to other trees, such that the cutting will grow on the new plant. Most frequently this is done onto a “rootstock” – a cloned root system produced through asexual propagation – to make a tree that will grow one specific variety of apple. The rootstock determines many traits of the grafted tree, such as size, precocity (how early and often it will fruit), and resistance to diseases. (Photo of apple tree rootstock by Nathan Wojtyna).