Mapping the Continental Ambitions of the United States

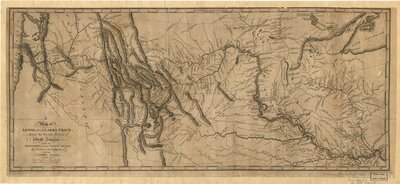

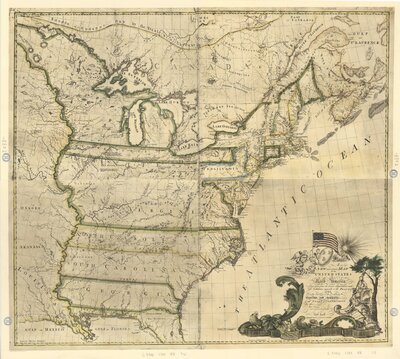

From the start, Lewis and Clark’s writings were appropriated by the rituals surrounding political authority and statesmanship: in quoting geographical coordinates, the cartographic grid, and the map, the American president took possession of the expedition’s narrative not only as a state-funded project but also as the basis of political capital. “Taking possession of the land means integrating new territories into the living processes of the appropriating state.” By submitting the still-incomplete expedition map to Congress, Jefferson presented the textuality of geographical writings - as British and other colonial officials had since the sixteenth century - as the primary evidence for defending a politically ambitious decision.

In his presentation, the Lewis and Clark map became the bureaucratic blueprint for what would follow: other expeditions, more detailed accounts, the Indian removal policy, the Homestead Acts, the violent encounter with and erasure of the Native American population. In short, through Lewis and Clark’s letter and map, Jefferson as head of state began the story of the federal project of the territorial enclosure and western colonialization, the national plot of an American continental empire

- Brückner, Martin. The Geographic Revolution in Early America: Maps, Literacy, and National Identity. Published for the Omohundro Institute of Early American History and Culture by University of North Carolina Press, 2006. pg 206