EXPLOITATION

Located in the hallway from the College of Human Ecology Commons.

Birds are visually fascinating creatures: their feathers come in a spectacular array of shapes, textures, and colors, contrasted with beaks, scaly feet, and sharp talons reminiscent of an evolutionary past. It is no surprise that their feathers and body parts have adorned peoples from around the world as symbols of wealth, power, luck, and protection for hundreds if not thousands of years. But, with increased global trade and the industrialization of European and American fashion industries in the 19th and early 20th centuries, the nature of feathers worn on the human body changed dramatically. In an industry fueled by artificial obsolescence, changes in fashions for feathers (particularly within the women’s millinery industry) meant an insatiable demand for birds in the late 1800s. Historians estimate that by the early 20th century, 300 million birds were killed for fashion.

By the late 19th century, millinery centers of New York and London were fueling a sordid feather trade. Hats might include entire birds as decoration, like the Greater Bird-of-Paradise (Paradisaea apoda) on the velvet hat to the left, or plumes, like the collection of egret feathers. During the 1890s, the fashion for egret plumes—a feather that only appears during breeding—threatened the future existence of the bird. Because these plumes only appear during breeding season, the death of a single egret actually meant the death of an additional 3-4 nestlings. In North America, for example, more than 95% of Great Egrets (Ardea alba) were killed in the late 19th century. Egrets were facing extinction, and it was the millinery industry and fashionable women consumers who were the culprits; however, fashionable women were also central players in the eventual safeguarding of these birds. Minna Hall and Harriett Hemenway were fashionable Boston women who were determined to save the egret. They organized a boycott against the plumes, and in 1896 founded the Massachusetts Audubon Society. Other states began to form Audubon societies and advocate for the protection of birds. The eventual passage of the Weeks-McLean Act in 1913, and later the Migratory Bird Act of 1918, essentially outlawed the plume trade and has protected migratory birds ever since.

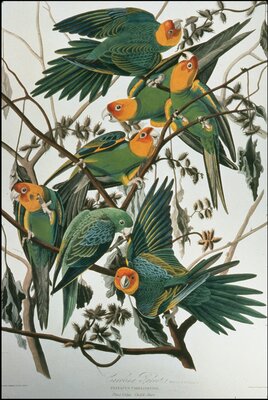

Unfortunately, conservation efforts did not come quickly enough for all birds. Another desirable bird for fashion accessories, the Carolina Parakeet (Conuropsis carolinensis), was extinct by 1918 (the last confirmed sighting in the wild was 1910). The Carolina Parakeet had the northernmost range of any parrot and was indigenous to the United States. Its local availability, along with the bright coloring that differed dramatically from other local birds, made the parakeet highly sought after as an adornment for hats, fans, coats, and gowns. The ensemble to the right, an 1886 “walking dress,” features a brooch made of Carolina Parakeet tails and scalps.

Throughout EXPLOITATION, fashion objects featuring bird feathers were displayed alongside the scientific specimens and early illustrations of those same birds. Bird specimens, also sometimes called “study skins,” are an important resource for ornithologists and are on loan from the Cornell University Museum of Vertebrates. At the bottom of this page is a section highlighting these “study skins” under the section BIRD SPECIMEN. We use them here to provide a visual reference: can you tell from which part of the bird the feathers on the fashion item came? How much of the bird is used in the design? We do not often consider the natural resources, nor the human laborers, that are exploited to produce our clothes. By placing specimens and illustrations alongside garments, we hope to draw attention to the ethics of production.

Is it possible for feathers in fashion to be ethical and sustainable? Government regulations and protections for migratory birds in the early 20th century have forced fashion designers to obtain feathers from other sources, like domesticated birds and feathers that are by-products of the poultry industry. For example, contemporary milliner-taxidermist Rachel Schlass used an entire Chukar (Alectoris chukar), a large quail-like bird native to central Asia but introduced to North America for hunting, which she acquired from a Pennsylvania hunter who would have otherwise disposed of the skin. Schlass’ hat is shown on the left side of the adjacent image. By contrast, the fedora-style hat, shown on the right side of the image, only includes the bird’s distinctive patterned flank feathers, which means that multiple Chukar partridges were likely killed for this design. Interestingly, this hat was designed by the “King of Millinery,” Jack McConnell, who used a distinctive dyed red feather next to his label to authenticate his designs. Feathers continue to frequent the fashion runway and red carpet, and find their way into our wardrobes as hair pieces, earrings, boas, and trims. Fashion designers and consumers alike cannot seem to break their age-old fascination with feathers.

Feathers are a scientific and aesthetic marvel: made of beta-keratin, a protein similar to that of alpha-keratin found in human hair and nails, they are fractal-like on the micro and macro scales. The fractal structure of a down feather, for example, traps air and keeps body heat from escaping while preventing cold air from penetrating. For this reason, the downy feathers found on the breasts of birds are often used for functional winter clothing, like the late 19th century hand muff in the image to the right, which is made from the entire breast and belly of a grebe. Material scientists have struggled to develop an alternative to down: it remains the warmest, lightest, and most comfortable insulating material. It is also renewable, biodegradable, and recyclable. As scientists and designers, we have not yet developed an alternative better than that found in the natural world.

Down feathers are also beautiful and appear soft and fluffy, like the Marabou down jacket featured on the left. The jacket is paired with a turkey feather cap of similar coloring in order to display the contrast between the two types of feathers: the contour feathers found on the hat, which include a vane (the outer, smooth, sleek part of the feather) and filament fiber (the softer, wispy base of the feather) and the downy feathers of the jacket, which were historically sourced from the undertail of the Marabou Stork (Leptoptilos crumenifer). “Marabou” became a catch-all term used in the fashion industry for down trimming from any stork, and the scientific specimen on display here is a Wood Stork (Mycteria americana), while the backdrop illustration is dated to 1838 and depicts a Marabou Stork.

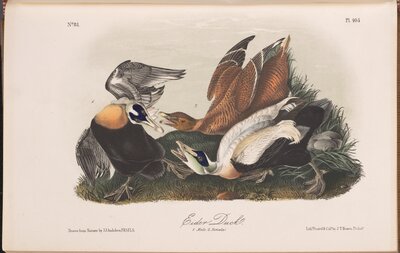

Down is the most common feather used in fashion today, but we don’t see it: it is more commonly sandwiched between layers of fabric and utilized for its insulating properties. In the fashion industry, down is evaluated by “fill power” (a measure of the space an ounce of down creates) and “fill weight” (the mass of down within a garment). The highest quality down has high fill power and low fill weight. Recently, sustainably-minded companies like Patagonia have begun to invest in recycled down, which diverts old cushions, comforters, and pillows from the landfill by repurposing the down into new coats. On the right is a Patagonia recycled down children's jacket with a feather-inspired textile design. This jacket is likely filled with recycled goose or duck down. The most superior and arguably most sustainable down, however, is Eiderdown, which is considered the best, most insulating down in the world. It is sourced from Common Eiders (Somateria mollissima), a group of migratory sea ducks that live in very cold northern coastal regions of Europe, North America, and Siberia. The scientific name, Somateria, reflects the insular nature of the down: soma means body, and erion means wool. Eiderdown is gathered from eider nests, where female ducks pluck down from their chest to keep their eggs warm and out of sight from predators. While male eiders also have down, they do not help incubate eggs or contribute down feathers to the nest, thus eiderdown harvested from nests comes only from females. Colonies of eiders in Iceland and Canada are cared for by humans, who carefully harvest down from nests with as little disturbance as possible (an ethically-sourced eiderdown comforter will cost upwards of $16,000). Because eiderdown is a limited and expensive natural resource, goose and duck down are more commonly used for garments and home textiles, with 80% of the world’s down sourced from China.

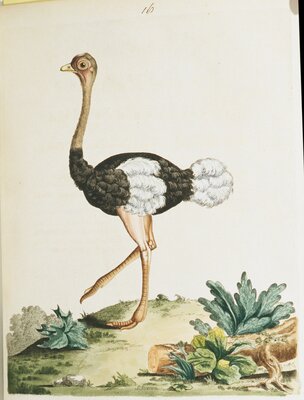

The final two items that were shown in this portion of the exhibition both represent and utilize feathers. In the Patagonia children’s jacket, mentioned earlier, the designer has brought visibility to the down hidden between layers of fabric by using a feather-inspired textile design. Likewise, the Patrick Kelly dress designed for his very last fall/winter collection in 1989, shown on the left, uses ostrich feathers along an asymmetrical neckline that connects to a brocade textile design inspired by those same feathers. Both pieces occupy a complex space between inspiration and exploitation, with feathers ethically sourced and design work that pays homage and brings visibility to those same feathers.