What Was the Role of Home Economics in the Life of the University?

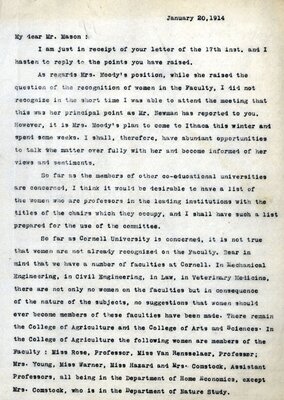

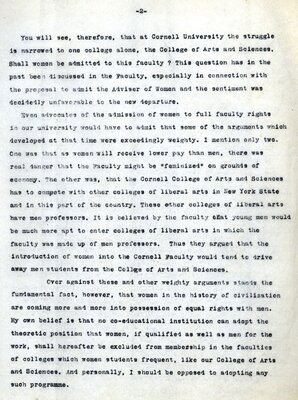

Cornell's home economics program had to struggle for autonomy and equal status within the larger university. Although a small number of women were granted professorships, there was real resistance to admitting more women to the faculty. In a 1914 letter Cornell President Jacob Gould Schurman wrote, "as women will receive lower pay than men, there was real danger that the faculty might be 'feminized' on grounds of economy." He continued, however, "My own belief is that no co-educational institution can adopt the theoretic position that women, if qualified as well as men for the work, shall hereafter be excluded from membership in the faculties of colleges which women students frequent..."

In the early years, home economics struggled to be independent and separate from the College of Agriculture. In 1919 the Department of Home Economics became a school and in 1925 it became a college, but it was not until 1941 that the College of Home Economics actually had its own dean.

After World War II, the struggle changed. Home economics was, for the most part, an applied science, which put it at a disadvantage in the modern research university, where basic research generated greater status and funding. Home economists were challenged by a new academic ethos that placed overwhelming emphasis on specialized knowledge and discipline-based research that was abstract, objective and theoretical. Because they were by and large generalists who translated and applied information from many fields, home economists did not conform to the postwar ideal of academic social science. Moreover the college was very much a community of women, and both of these factors contributed to a loss of status. By the late 1960s, however, new views about women challenged Cornellians to rethink the role of home economics in the research university.

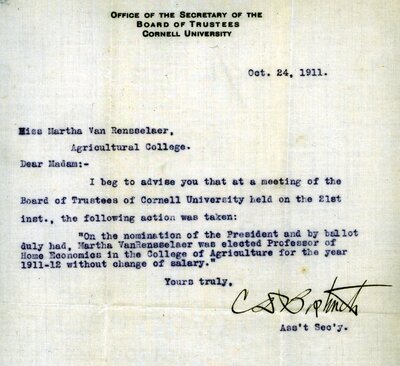

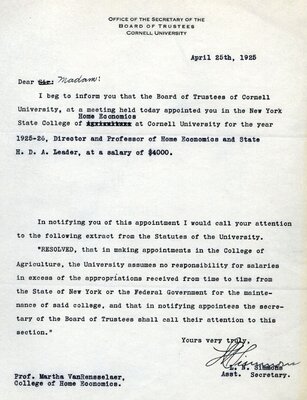

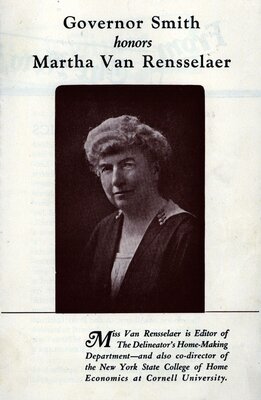

"Lecturers" to "Professors"

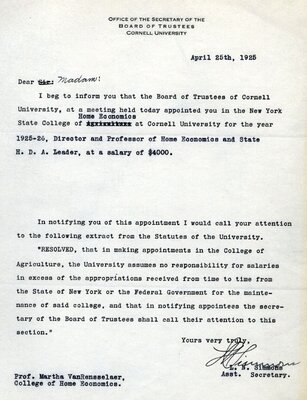

Martha Van Rensselaer and Flora Rose initially held the title "lecturer" in the College of Agriculture. After many debates on the issue in university faculty meetings, in 1911 they were appointed professors. These letters from the Board of Trustees stated the change in title and the fact there was no change in salary.

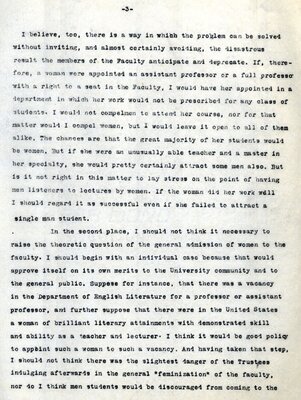

Women on Faculty, 1914

Cornell President Jacob Gould Schurman explains his view of women on the faculty in this 1914 letter.

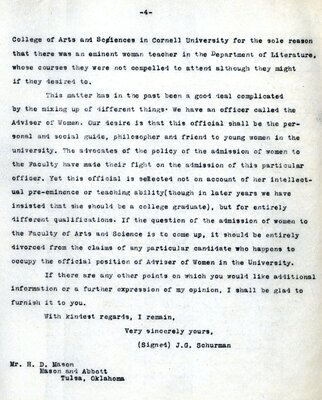

"Department" to "School" of Home Economics

In 1919 the Department of Home Economics became the School of Home Economics. The school was still within the College of Agriculture with no change in administrative structure of funding.

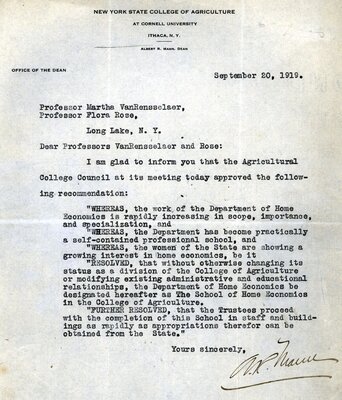

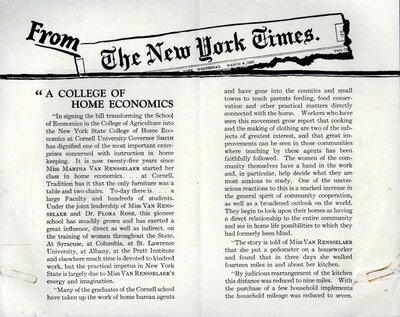

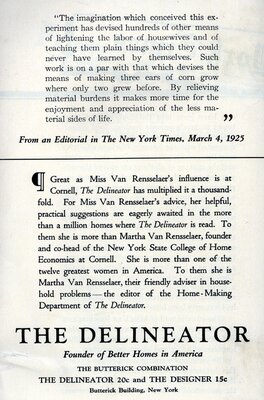

A dinner was held in honor of the 1925 change from the School of Home Economics to the College of Home Economics, and Martha Van Rensselaer was recognized by the state for her accomplishments. The administrative structure of the college did not change, as the dean continued to be of the College of Agriculture. It would be sixteen years later before the College of Home Economics had its own dean.

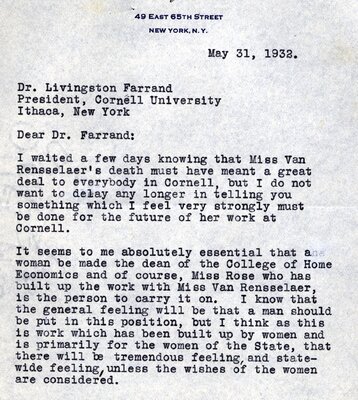

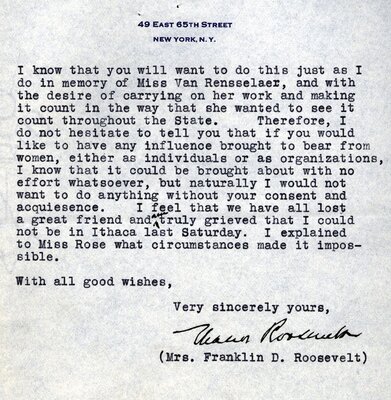

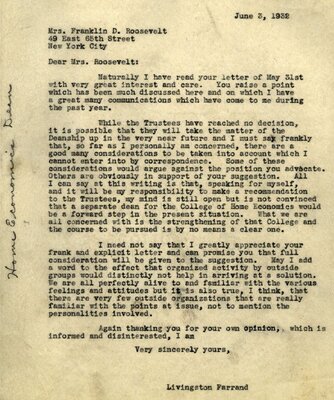

Eleanor Roosevelt and President Livingston Farrand

Shortly after the death of Martha Van Rensselaer in 1932, Eleanor Roosevelt wrote to President Livingston Farrand requesting that Flora Rose be named dean of the College of Home Economics. Farrand's response was polite, but not in favor of her suggestion.

First Dean: Sarah Blanding

Sarah Blanding in 1941 became the first dean of the College of Home Economics and the first woman dean at Cornell.

Female Faculty Members, 1960

This home economics faculty meeting in the 1960s illustrated the predominance of women on the faculty.

The Cornell Widow

Women struggled for recognition not only in administrative areas, but also in student life. In this 1914 issue of a Cornell humor magazine, the Cornell Widow, male students mocked home economists' money-saving suggestions.