Case 2: Travel

Settler Colonialism & Americanization

In a world defined by social, economic, and mechanical mobility and settler expansion, the home economist freely traveled across geographical and political boundaries disseminating their art of living. Often referred to as “Americanization,” these professionals responded to changing social, industrial, and economic conditions of daily life in the U.S. through their educational forays across New York State. While the so-called “frontier” may have been declared officially closed in the 1870s, dress and the home economists’ dissemination of knowledge about it across NYS remains (as Elizabeth Wilson provocatively put it in 1985) at the ever-expanding “frontier” separating the self from the non-self, the self and the other (2003: 3). Circulating through the NY landscape themselves as well, in Case 2: Travel I consider home economists on the move. This case reflects on the physical distance and material infrastructure between Cornell’s College of Home Economics and the rural farm’s they served and studied. It also reveals some of the ways that cultural practices and stylistic trends used open spaces to spread their ideas not only person-to-person, but across the territory as a whole.

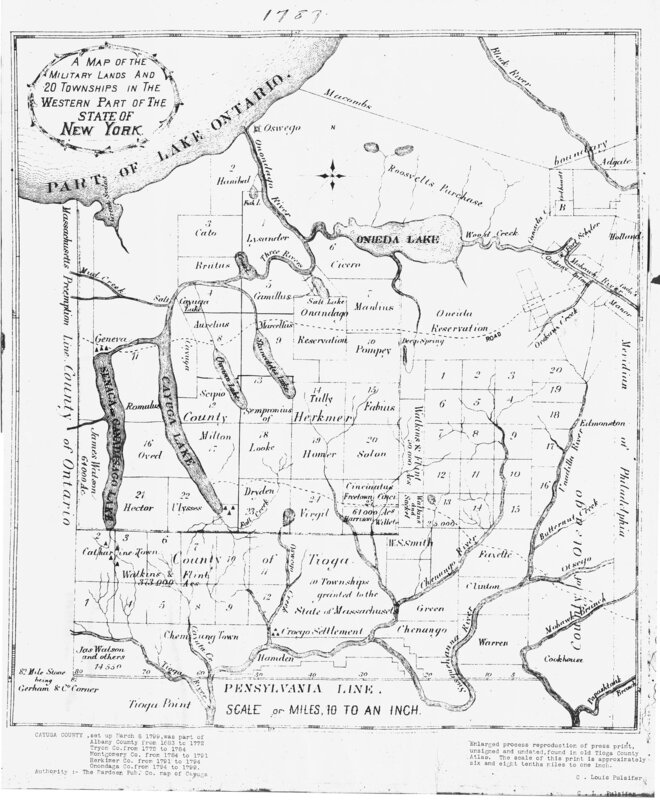

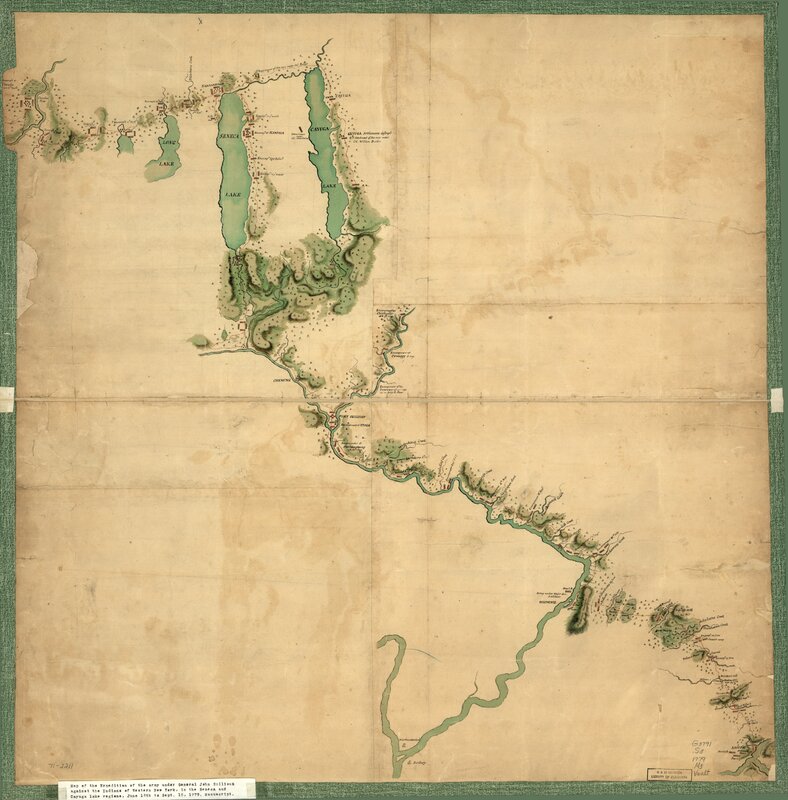

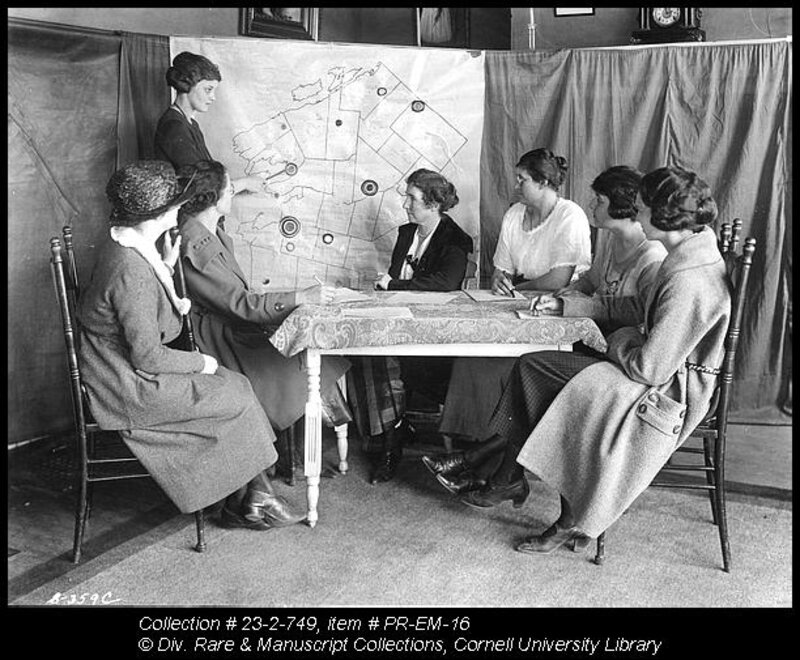

Bolstering the distribution of private property across NYS, the history of Native land dispossession cannot be removed from any consideration of land become geographic territory. This map from 1787 follows the military expedition of General Sullivan into Cayuga Nation territory by no more than a decade. Extension agents like these women organized their travel to reading and study-groups, home-bureau organizations, and private homes according to the County lines based on the initial “military townships” used to organize white settlers’ across the state. The records of their analysis of the domestic labor that remain in the archive today continues to reflect this settler colonial organization. When imagining these professional women traveling from Cornell to a rural farm home, it is important to remember that even in 1916 they were seated on trains as well as in busses and cars that traversed paths cutting across the boundaries between the Onondaga Reservation, Manlius County, Oneida Reservation, and back through Pompey and Fabius Counties.

The fast expansion of car travel in the early twentieth century is often associated with the appearance of affordable new vehicles. Equally important were new techniques of road building as hard-packed dirt roads crisscrossed the state in growing numbers. As historian Paul Starr pointed out, the expansion of road systems was a fundamental requirement of the rise of professions in the United States ([1982] 2017: 65-71). While allowing home economists to travel far greater distances in a single day, they also created some novel difficulties. The tan duster on the right of the case presents what was popularly known as a “motoring jacket” or “car coat” (2014). Adapted from the dusters worn on horseback, this motoring jacket has brown piping and a cape wrapping over the shoulders to form openings for the arms. The lack of sleeves would have made it easier to pull over one’s dress and the thin material made it possible to wear even on warmer days to keep the dust off while traveling out to a farm to deliver a home demonstration.

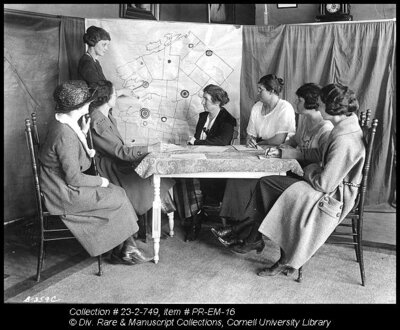

At the center of this scene a group of three home economists have arrived at their destination and are unloading supplies from one of their vehicles (Brumberg 1997: 191). As seen in this staged photograph in front of the home economics building, extension workers brought model appliances, travel sewing machines and stoves, and other supplies with them to home demonstrations. The row of women in the background await the three women unloading the car to enter the clapboard house behind and begin their demonstration. One woman can be seen holding what appears to be her own gummed-tape form for the upcoming demonstration.

Across to the left, another house stands above a maintained lawn of cut grass in Geneva, NY. Below this house are displayed to garments donated by Annette Warner, author of the bulletin “Artistry in Dress” featured in Case 5. While the two garments appear in stark contrast with one another, they both speak to large outdoor spaces. Another example of a motoring jacket, Warner’s brown coat from 1900-1908 has a double-breasted front, prominent gathered shoulders, and crisp V-shape of the back that gives it a military feel. The coat features a princess line, which while maintaining something of a cinched waist look from the nineteenth century and was still likely worn with corsets, firmly did away with other shaping tools like the bustle or crinoline giving a less inflected line to the body’s silhouette. Rather than a waistline and darts, the close fit of the “princess line” relies on shaped patterns connected by long seams you can see expressed down the front and back of the garment. Narrowing in from the shoulders and tightly overlapped high on the waist, the tucks open downward into pleats making room for other garments beneath the jacket as well as sitting in a car or train and walking freely.

In contrast to the structured lines, Warner’s mauve, chiffon dress from 1923-24 features flowing lines and playful decorative details which, in Warner’s words, can be “associated with joy, freedom, and festivity” (36). Worn on top of a simple silk chiffon slip, the mauve dress displays a plunging V neckline, medieval style sleeves bisected and gusseted at elbow, and an exquisite floral motif embroidery around the hipline. From here, the skirt falls in separate panels producing handkerchief points just below the knees of the wearer. Wide sheer sleeves, troubadour sleeves, and other 1920s styles also belong to this cultural trend. While the dress offers a familiar silhouette for 1924 (with the embroidery marking only the hint of a waistline), when we consider the occasion for which this dress might have been worn, it tells another story.

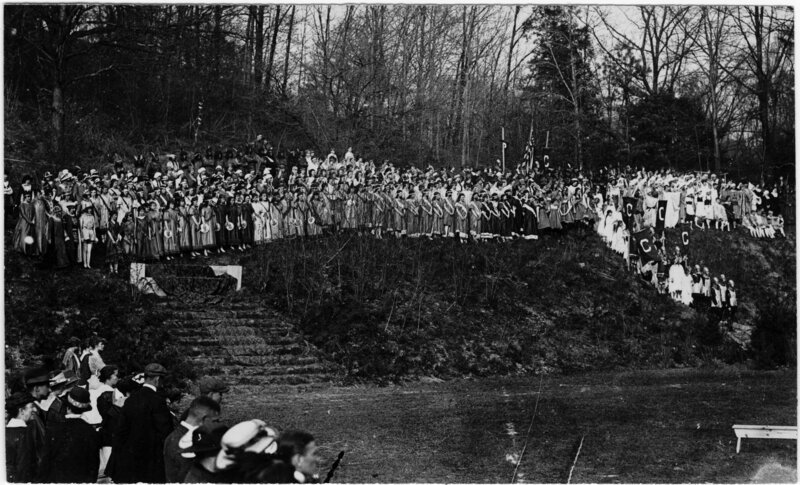

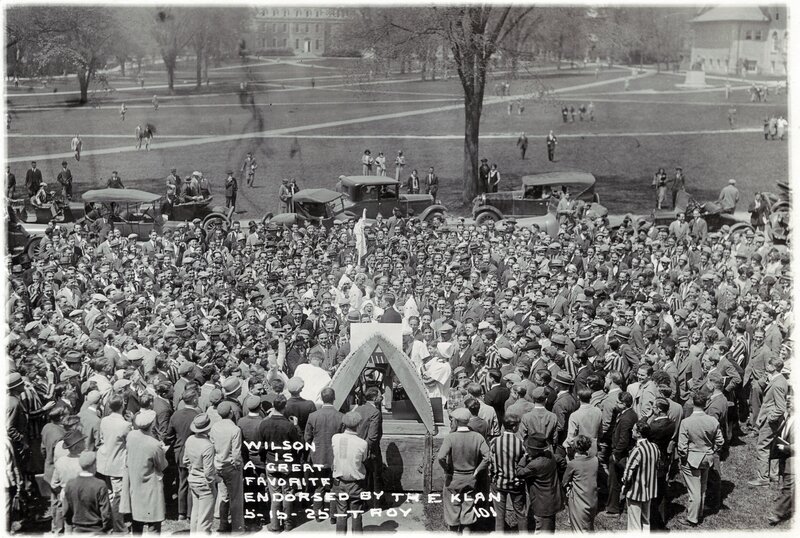

In her bulletin, Warner repeatedly emphasizes the importance of matching the garment to the occasion. This chiffon dress would perhaps have been appropriate for one of the Women’s pageants that Cornell held in celebration of their new female graduates. Cornell’s Women’s Pageants like this one from 1916 were held near Beebe Lake. The female graduates dressed as they imagined fairies might with flowing robes and lithe movements, while the men who participated wore long, colorful tunics and mock-iron helmets as if they had recently returned from the set of a movie depicting the crusades. Pageantry like this was popular in the early twentieth century amongst avant-garde groups in Europe just as much as with local organizations and student groups affiliated with the Klu Klux Klan. As Carol Kammen has pointed out, the KKK was so normalized in and around Ithaca at this moment, that the archival traces of their local chapters seemed more focused on planning community picnics than any explicit discussion of Race (quoted in Reynolds 2017). In 2017, Nick Reynolds published “The Ugly Truth: Remembering Ithaca’s Klan Years,” in which describes a community parade in October of 1925 culminating in what was then called the Circus Flats (now home to the Ithaca Skate Park across from Wegman’s) for a cross burning that was described as “an attractive spectacle.”

Pageantry also held an unexpected relationship with professionalism. The American Institute of Architects (AIA) included a full section of their own institutional history dedicated to the growing role of pageants in their professional proceedings (Saylor 1957). In their 1925 ceremony awarding the AIA Gold Medal to Henry Bacon for his design of the Lincoln Memorial in Washington D.C., architects stood at the steps of the monument in custom-made robes meant to look like those worn by medieval guildsmen and stonemasons. Their anachronistic costumes went hand-in-hand with the general popularity of the eccentric Gothic stylings inspired by architects like H.H. Richardson and authors like John Ruskin, who was unsurprisingly often quoted by Cornell Home Economists and the main inspiration for Sage Hall and Sage Chapple. Central NY continues to host similar stylistic anachronisms with the continued prominence of Greek Revival architecture throughout the region (and as depicted in this case). Although these architectural reference points may at first seem unrelated, it speaks the same cultural trends reflected in Warner’s mauve, chiffon dress with it is noteworthy “medieval cuffs.”