Case 5: Reading-Courses

Reading-Course

The Cornell Reading-Course for Farmers’ Wives was renamed and reformatted numerous times in its first three decades of operation. Under the title “Farm Home Studies” the very first bulletin was distributed in January 1901 and included guidelines on how to form a “reading club,” an outline of the first five lessons, and some general suggestions on how to run each meeting (RMC 23-2-749, Box 46, Folder 1). Cornell’s Reading-Course was widely distributed first in New York State, but soon spread at least as far as Montana, and formed a highly effective means of disseminating solutions to the new problems of the home. For MVR, these bulletins were a means “whereby scientific training is brought within their reach at home” (November 1902). Along with the Reading- Course came a supplement called a “Discussion Paper.” These additional booklets inverted the relationship between home economist and reader, and rather than offering useful information, asked a series of questions. Through this give and take, home economists at Cornell and their audience of rural women expanded the knowledge base and relevance of the discipline. The Reading-Course constructed the foundation of Cornell’s home economics program establishing at once a focused and relevant topic of study, a clearly identified audience, and a network of relationships that could both circulate and provide data. These humble publications were the mechanism that allowed home economists to develop expertise and forge community ties making their status as professionals possible.

Case 5 includes plays a selection of rural bulletins published between 1913 and 1926. In this case I argue that home economics at Cornell institutionalized forms of whiteness within these publications, the knowledge they produced, and the communities they forged toward the establishment of home economics as a profession. I present this whiteness by demonstrating how these bulletins bring together household management and efficiency, on one hand, with cultural history, affluence, and historicity, on the other. The two bulletins on “Saving Strength” and “Artistry in Dress” show the impact of these intertwining trends in the body. A fact made more explicit by the large-scale reproduction of a “discussion paper” at the center of the case. Filled-out and returned to Cornell by Mrs. Edith V. Enders of St. Lawrence, NY, the way this Discussion Paper frames questions and Enders responded to them dramatizes the implicit expectations of the Reading-Courses.

Cultural & Technical

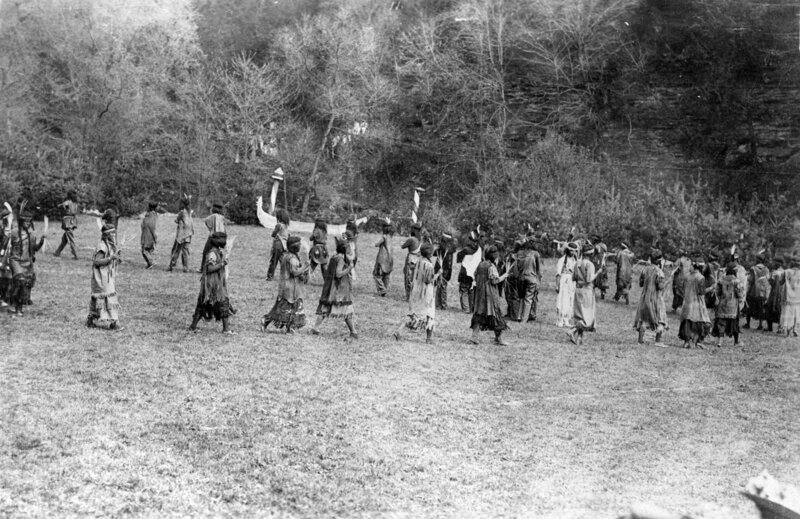

The Reading-Courses presented in Case 5 demonstrate how home economics intersected cultural history with household management. Two bulletins from the “rural life series” written by faculty member Blanche Evans Hazard focus on local histories. In response to the many positive responses to the 1913 bulletin “A Story of Certain Table Furnishings” (Bulletin 51), Hazard offered one on “Attic Dust and Treasures” (Bulletin 61). It seems that many readers had uncovered stories of their family histories through heirlooms they found during Spring cleaning efforts to sanitize the home (Bulletin 2), rid it of dust and germs (Bulletin 12), and apply what they were learning about household bacteriology (Bulletin 31). These heirlooms included documents showing how transportation systems were financed, old flintlock muskets, quilts thought to be the products of Colonial era “quilting bees,” as well as indentures, slave manumission documents, and old account book pages. A year later, Hazard continued with an issue titled “The Primitive Woman,” which asked: “What can the New York farmer’s wife give to this Indian sister, and what can she receive from her? Will she be ready to welcome the successful Indian artist, or craftsman, or farmer, who settles in her midst? Will she be willing to aid actively in securing for the Indians on the reservations the best and fairest means of civilization and its benefits?” (Bulletin 91: 201-202). Preceding the founding of Cornell’s Indian Extension Program in the 1920s under Dr. Erl Bates, Hazard sought out a collaboration with Haudenosaunee representatives to develop an Indian Pageant. The bulletin on Primitive Woman included a number of photographs and explanations of the event.

Along with her emphasis on Anglo-Saxon and Dutch ancestry before, Hazard’s bulletins are just two examples of how cultural histories were a part of the “science” of right living taught by Cornell home economists. It’s not that speaking about a certain audience’s Dutch ancestry or that seeking out collaboration with unfamiliar neighbors is itself racist, of course. However, exploring and taking care of the treasures in “our” attics describes a social status and level of wealth premised on whiteness, one underlined by the fact that “New York women” and farmer’s wives have much to learn from “the daily life of uncivilized and primitive woman of the past and present” (201).

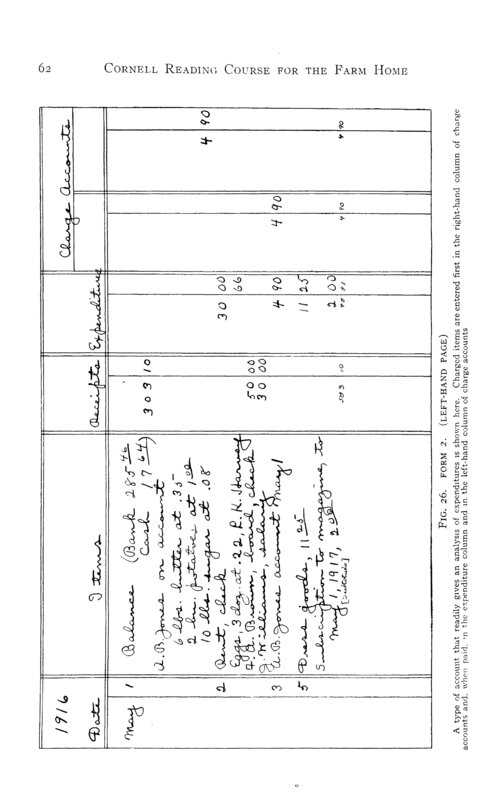

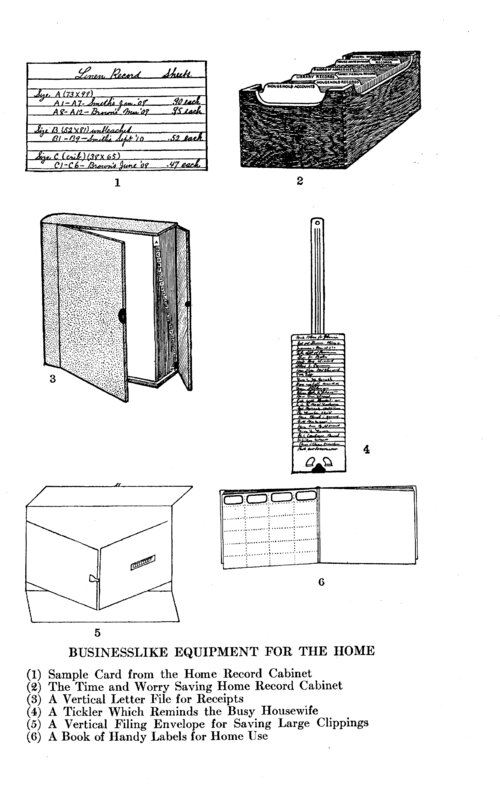

Bulletins 39 and 110 are both from the “farmhouse series” and seem to focus more plainly on the technical aspects of home management. In Bulletin 110, Edith Fleming Bradford’s presents the importance of maintaining the household accounts. Paralleling the more well-known accounts from Christine Frederick in her 1913 book The New Housekeeping: Efficiency Studies in Home Management, Bradford’s bulletin emphasizes that while record keeping like this has been prominent “since Xenophon’s time,” the complexities of money-relations today makes it all the more necessary (41).

Helen Binkerd Young, who graduated from Cornell’s architecture program in 1900, explains the importance of redirecting country life by remodeling farm buildings for the future in Bulletin 39. While “health and happiness in the home are not marketable commodities,” Young points out, if considering the longevity of our choices “real profit would accrue” from “household investments” (153). Spoken with authority, Young’s advice warns of the “waste of money and labor” and even the “futility” of developing farm property without an overall working plan that carefully fits each aspect of farm management together into a single workable system: “organized farming and organized housekeeping are the order of the day” (154).

Overall, Young’s article focuses on the technical and aesthetic details of planning the farmhouse, just as her others detail the arrangement of furniture (Bulletin 7) or household decoration (Bulletin 5). However, what some might take as a minor detail, upon closer inspection exposes a deeper and more violent set of assumed cultural reference points. Continuing her insistence on organization above, Young writes that “a well-planned farmstead is more economical, more orderly, more beautiful, and more saleable than one which, like Topsy, ‘just growed’.” (154) Young’s critique of the “makeshift” site planning on farms across NY is not just a condemnation of poor foresight, it is an adamant declaration of the values implicit in “the order of the day”: economy, order, beauty, profit. An order, it seems, that found its most apt analogy with a reference to Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin. One can only assume that Young expected her readers to know that Topsy was a character in Stowe’s novel. Topsy was a young Black girl born enslaved. In the book, when she is asked about her father, it’s explained that “she wasn’t born, she just growed,” in other words, Topsy’s mother either did not know or did not tell Topsy who her father was. Thus, Young is aligning the orderliness or beauty of farmstead site-planning with the informality of a Black woman’s reproductive origins in a slave economy. At best a callous off-hand remark, Young’s analogy reveals a then popular understanding of the spectrum between a futile informality and good planning that was closely associated with a then popular understanding of the spectrum between blackness and Whiteness.[4]

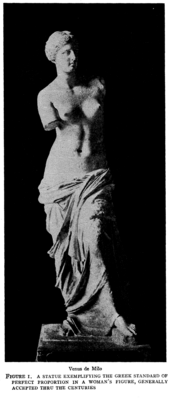

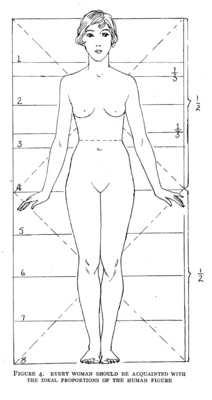

The final two Reading-Courses in Case 5 illustrate how cultural histories and advice on household management intersect in the body. Annette J. Warner’s “Artistry in Dress” brings attention to dress design focusing on the design and proper fit of the everyday dress (Bulletin 144). Warner’s bulletin reconceptualizes the narratives of prior bulletins as a set of design principles. Here, Warner draws on both cultural histories and technical capacities for her authority. That is to say, she draws on the whiteness embedded in both for her enactment of design expertise. References to Ancient Greek and Italian Renaissance history like many of the other authors, Warner displays the ideal proportions of the female body with a sculpture, a painting, and diagram. She explains: “A general agreement upon the ideal proportions of a woman's figure has been arrived at thru centuries of observation and study. According to these conclusions, a woman of perfect proportions is from seven and one-half to eight heads high” (13). Interestingly, Warner’s point is not that we ought to all look the same or all rigorously adhere to the rules, but rather think for ourselves. And yet even as “Artistry in Dress” intends to serve as a guideline for rural women so that they might think for themselves, this form of self-reliance continues to rest on the “general agreement upon the ideal proportions of a woman's figure.”

Compiled initially by MVR and later amended with the help of Emily Bishop, the fifth bulletin is titled “Saving Strength” (Bulletin 138) Although first distributed in 1903, this issue of the Reading-Course appears to have been particularly popular and was republished at least four times (1903; 1905, RMC 23-2-749, Box 46; 1912, 1920). The issue in the case appeared in 1920 with a completely new set of photographs to illustrate what was roughly the same body of text. “Saving Strength” offered advice on how to balance hard work with good health by avoiding physical and mental fatigue. Bishop and MVR begin by recommending the importance of rest and relaxation, vacations, and even exercise in the effort to avoid general fatigue. Extending on to body posture and spatial arrangements most conducive to efficient energy expenditure, “Saving Strength” ultimately imbues bodily comportment with commonplace moral assumptions. Case 4: Posture will explore the way photographs in this bulletin linked good behavior with the effective management of resources, however the link between can be seen in the words of one rural women through a close look at the Discussion Paper that came with “Saving Strength.”

“Nor knoweth thou what argument thy life to thy neighbor has lent.”

As mentioned above, these Discussion Papers allowed home economists to survey their readers; they also allow us some insight into the effect of the Bulletin’s lessons on everyday women. Each bulletin not only sent out information to New York farmhouses, it also created an avenue for gathering more data for the home economist. The questions they asked of their readers required them to explain what they were already doing even as they had only just read through the bulletin telling them how they ought to have been doing it.

There are two important points to draw from this method of survey: first, the reader is under a constant pressure of giving the “wrong” answer. The majority (if not all) of the questions prefigure an answer; for instance, in the March 1905 supplement, part of series No.15 “Saving Strength,” they ask: “Is a proper poise as attractive in a woman in a kitchen as to one at a drawing-room reception?” To which one respondent, a Mrs. Edith V. Enders of St. Lawrence, NY wrote, “Yes, entirely equally so.” And second, the process itself requests that members place themselves under scrutiny. Seemingly innocent questionnaires, the anxiety these self-managing documents produce is palpable, and it ranges from shame at not being good enough, to anger at others for not trying hard enough, to pride at having altered one’s behavior appropriately to the betterment not only of oneself, but of the world at large. “Do you belong to a rural study club? If not, is there an opportunity to form a club in your neighborhood?” The same Mrs. Enders responds here as well: “No. I hope so. I will try. I have often wished there was one. One for the women and a separate one for the men. The Rev. Chas. Atwood and the Rev. B. Shaw might head the men’s. I, with the help of some more, would not object to head the women’s.” The anxiety in these words is perfectly expressed by the many crossed out phrases and the palimpsest of erased pencil lead beneath them and visible through the paper from the next page of the document. Many of the discussion papers are similarly overtaken by markings like this; responding, erasing, and re-drafting seems necessary to ensure one has recognized and supplied the “correct” answer.

[4] Here I refer to blackness with a lower case “b” because the understanding of blackness illustrated by Stowe’s novel does not refer to Black cultural traditions, but to the interpretations of white people like Harriet Beecher Stowe. Furthermore, here I refer to Whiteness with an upper case “W” because this analogy is a form of White supremacy.