Case 3: Dress Forms

Industrial Self-Fashioning

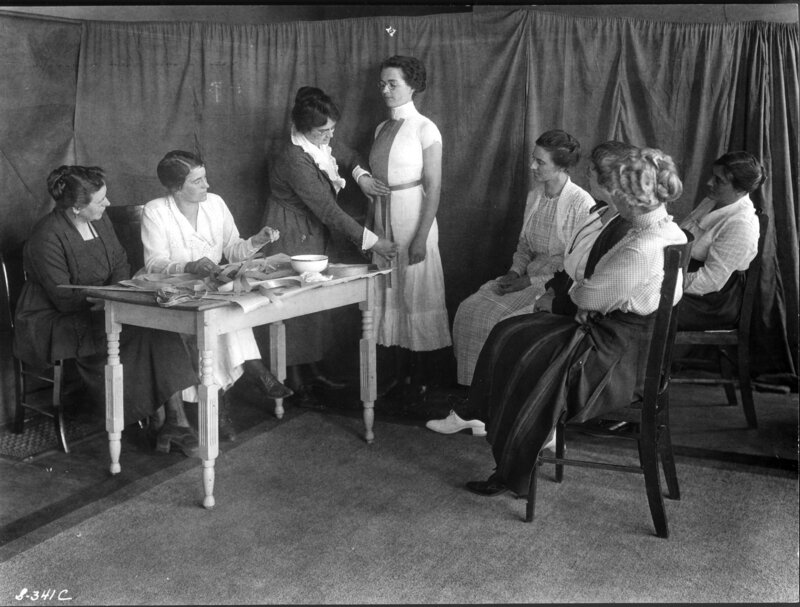

Emblematic of just how invisible the legacies of whiteness often are, the gummed-tape dress form displays how home economists literally and metaphorically transformed the white bodies of themselves and their clients into supposedly neutral tools. The gummed-tape dress form was an affordable technique for women to make custom dress-forms of their own bodies. It was with clever tools like this that home economists effectively transformed the modern techniques of a turbulent world into a measured and straightforward service for rural farm women. While white bodies cannot be seen in the gummed-tape dress forms shown in this exhibit, their whiteness can. The social relationships forged in what has been called both the Progressive and Jim Crow eras remain present in the materials, bodies, and practices which made these forms possible. Fashioning one’s body along the lines proscribed by the dominant cultural expectations of whiteness need not (and often does not) look like whiteness. For instance, while this photograph could depict the custom-made dress form of any woman at all, in order for that woman to make her body look like this she would first need to have formed a community, a space, and a schedule according to the instructions laid out by Cornell’s rural bulletins. Case 3: Dress Forms analyzes how home economists closed the distance between the home and the factory that defined nineteenth-century femininity and domesticity.

While appearing less “industrial” than the adjustable steel dress forms patented in the 1880s, the gummed-tape form softens and familiarizes industrial movements and materials with intimate repercussions. Bringing the “factory” back into the “home” first requires that there be a very clear and obvious difference between them—what Davis calls a “cleavage between the home and the public economy, brought on by industrial capitalism” (1981: 12, 228). Furthermore, the idea of bringing the factory into the home is not bringing economic independence back into the home, but rather the products of factories for a self-improvement and personal “success.” Home economics responded to this cleavage by refocusing their attention on the relationship between industrial products and daily life through a new way of understanding processes of production, their bodies, and their garments. Using gummed-paper strips, shellac, and other chemical-based industrial products as part of a carefully articulated construction process, these homemade dress forms embodied a growing understanding of the link between specific bodies, “normal” women, and good design.

Homemade dress forms further reveal the social expectations and relationships underlying the fashioning of women’s bodies. Gummed-tape dress forms intertwined new systems of industrial production, reformed ideals of femininity, and the eccentricities of individual bodies within the friendly group dynamics of study clubs. The gummed-tape dress form demonstrates that what appears similar to mass-customization to our contemporary eyes, produced the opposite results in the early twentieth century at the high-point of Fordism and Taylorism. That is, as can be seen in Case 3, group workshops allowed rural women to begin to recognize the specificities of their unique bodies in the normal representations of the industrial body in mass publications like guidebooks and fashion magazines as well as visualizations of ready-made garments. Ironically, it was through the radical specificity of these home-made dress forms that rural women were interpellated into the world of standardization and mechanical procedure. These dress forms are a locally produced materialization resulting from the mass-circulation of industrial materials, popular publications and images, and of home economists themselves in the collection and distribution of their knowledge.

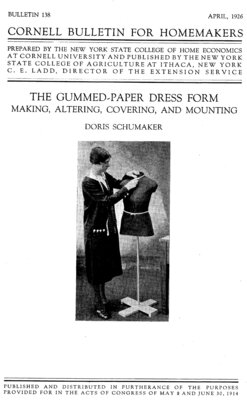

Making a Gummed-Tape Dress Form

According to Bulletin 91, the first in the series of five, the homemade dress form is “an effective labor-saving device” with two central aims: for fitting garments to one’s own body, and for duplicating “the figure of the model in every way.” (1924: 3, 14). Because it is possible to build a form on a body and not accurately duplicate the model’s figure, the bulletin insisted repeatedly that women closely follow the directions laid out for making the dress form. They were also “time and energy saving devices” that could be adjusted and re-made as their bodies changed from season to season. The built-in flexibility of these devices relied upon easy access to materials, tools, and an understanding of process over results—identical processes leading to custom results.

For this exhibition, a friend agreed to help me re-make a gummed-tape dress form according to the instructions laid out in the five bulletins. According to the booklets, the process is expected to take around 90 minutes, and perhaps a bit longer if undertaken by those without experience. Over two separate days we spent roughly 14 hours. More than anything else, it has become clear to me that making these forms should only be undertaken in groups no less than three (and probably no more than 6). They list five precautions to take when attempting one of these forms and I recommend following them all. Following the steps from the first bulletin took us a full 6 hours, which—as Schumaker and French point out—is longer than most people can stand still, shoulders back, feet 10 inches apart, breathing shallow and slow so as not to distort the damp gummed-tape. Removing the form from my friend’s torso was the most difficult part. Finding a way to fit scissors between the newly made form and your model’s skin requires care not only to avoid any scrapes, but also to prevent distortions in the dress form’s exterior surface.

Following the instructions as close as we could of course revealed the many small details that could not possibly have made it into the document itself. This again underlines the importance of the home demonstrations and first either witnessing or constructing a gummed-tape form under the watchful eye of a home economist. In our 14 hours of work, we made it through the first two bulletins (although we opted not to reproduce the base according to their instructions). The next steps, as presented in Bulletin 93, would be to cover the form in a tubular, black knitted fabric. The bulletin includes a pattern. This fabric is absolutely necessary if one hoped to use the dress-form. The thin, brittle surface of the hardened gummed-tape requires both the rigidity of the wooden base stipulated in Bulletin 92 and the black fabric to keep garments from slipping off the form and to provide a substrate for pins.

Unfortunately, I have not found archival accounts of gummed-tape forms, their use, or surviving models (outside of the photographs). I do believe the guidelines they set out in the bulletin, and that with experience these forms could be made quite quickly. The resulting objects, while light and stiff, are resilient enough to survive numerous adjustments. And yet, having gone through this experience and given the lack of archival material showing non-home economists with dress forms like these, I am left to wonder how “efficient” and “effective” they ultimately were. If the purpose of the labor and energy-saving devices was for at-home garment adjustments, it remains to be seen why custom-tailored clothes would have been so necessary in an era when ready-made garments were certainly available and even inexpensive. Poverty could well explain the necessity of re-modeling garments, as could wartime fabric rationing. And yet, the implicit assumption that effective and efficient garments are also custom-fit garments does not seem to stand up to the two central aims of these industrial devices (providing a duplicate of one’s figure for custom-fit garments) went beyond saving energy and time, and perhaps included aspirations not limited to the word “efficient.”