Historical Context

Gender, Race, & Expertise

Industrial Chemist Ellen Henrietta Swallow Richards helped organize a conference on the domestic sciences in 1899. Leaders in the field from around the northeastern U.S. gathered together at the Lake Placid Club in Morningside, NY for the first of what came to be known as the Lake Placid Conferences. Together they coined the term “home economics” (Elias 2006: 78; Weigley 1974: 84; Weigley 1976; Stage 1997: 6-7, 11-12). Dr. Richards underlined the role she and her colleagues set out for themselves calling out: “Who is to have the knowledge and wisdom to carry out the ideals and keep the family up to these standards?” The answer seemed obvious and she responded:

Who, indeed, but the woman, the mistress of the home, the one who chooses the household as her profession, not because she can have no other, not because she can in no other way support herself, but because she believes in the home as the means of educating and perfecting the ideal human being, the flower of the race for which we are all existing; because she believes that it is worth while to give her energy and skill to the service of her country and age (quoted in Weigley 1974: 82).

Echoing Catherine Beecher from a generation earlier, Richards believed that the only gap between a woman and her role and status as a professional is one of choice and training. The professional woman chooses daily domestic life as her duty and vocation not because she must, not because she has no other choices, but because she believes in the home and her control over it as a means of transformative power and social significance (Strazdes 2009). The professional woman must believe in the service she offers to her family, and thus to society as a whole (Weigley 1976: 254). Like the many other professions emerging at the end of the long nineteenth century, Home Economics would serve the whole of society by drawing upon scientific methods to research, analyze, and design a new “art of living.”

However, as Angela Davis (1981) has pointed out, the understanding of femininity championed by Beecher along with her sister, Harriet Beecher Stowe, well-known author of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, rejected those qualities that were required for Black women to survive enslavement. Davis explains that a Black woman’s survival within a slave economy required the acquisition and enactment of “qualities considered taboo by the nineteenth-century ideology of womanhood” because “the economic arrangements of slavery contradicted the hierarchical sexual roles incorporated into the new ideology” (1981: 11, 12). These enslaved Black women could not be encapsulated as a “weaker sex” for this would decrease their market value (1981: 8). Nor could they be considered a “family head” or “family provider” both because they were not men, and because all members of enslaved families or households were providers. And so, if the only difference between a woman and a professional at the beginning of home economics was a matter of training and the choice to believe that one’s home held transformative social power, where did this leave a Black woman in 1840, 1899, or 1920? Could she also choose to serve “her country and age” through her own arts of living and appear as a professional?

As numerous Home Economists noted, including Richards, nineteenth-century industrialization and the development of a market-centered national consciousness had transformed the house from a center of production into a center of consumption (Stage 1997: 7; Weigley 1974: 802). And it was in response to this seemingly radical shift in daily life that Home Economists worked to educate and support rural women across New York and elsewhere. Keying into this same observation, Davis notes that the call for a new professional during the material and legal transformations of domestic labor came hand-in-hand with the birth of the “the housewife and the mother as universal models of womanhood” (1981: 228, 229). The radical economic transformation following the end of the U.S. Civil War led to a cleavage between the public economy and the private home. Popularized and disseminated by women’s magazines and other publications, “women came to be seen as inhabitants of a sphere totally severed from the realm of productive work” (1981: 13). In other words, transforming the house from a site of economic labor in a pre-industrialized North America into the home as a protective haven from the tumultuous and often violent work of the capitalist marketplace paved the way for the emergence of a new model of femininity.

Taking it one step further, Davis pointed out that the abolition of slavery in the United States and the rhetorical transformation of domestic labor are not unrelated events. This is the case both in terms of economic viability and perhaps even more importantly in terms of the cultural value attributed to domestic labor and femininity. By transforming manual labor within households into a vocation, home economics and its scientific analysis of the “art of living” sought out cultural capital and social status. Speaking of the post-war, suburban home and the construction of race throughout the United States, Dianne Harris explained that kitchen appliances provided housewives with a new status by allowing them to avoid “the appearance of doing dirty, menial, and unskilled work” (2013: 195) That is to say, by avoiding the types of drudgery which had been historically “associated almost exclusively with hired, immigrant, nonwhite servants or with lower-class women,” housewives became white-collar workers. However, in the decades between the emergence of home economics and the apotheosis of the postwar housewife, the drudgery of housework was not so easily delegated either to appliances or to hired hands. In fact, amongst the study groups and Home Bureaus throughout New York, social status did not emerge from avoiding the appearance of laboring, but from the careful analysis of the labor necessary for the successful management of one’s body, house, and family. The transformation in the status of domestic labor cannot be solely associated with economic or technological shifts, but also needs to be understood in terms of cultural hierarchies and the dynamics of social status that were shifting in the concluding decades of the nineteenth century.

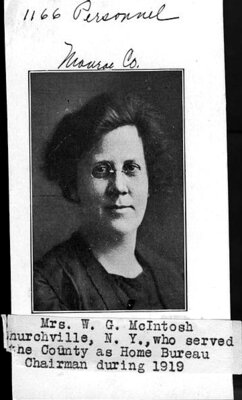

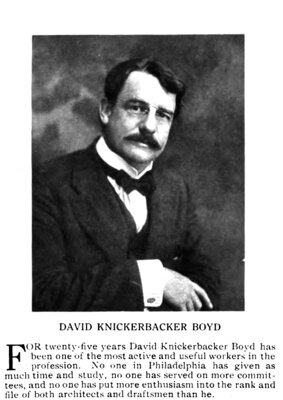

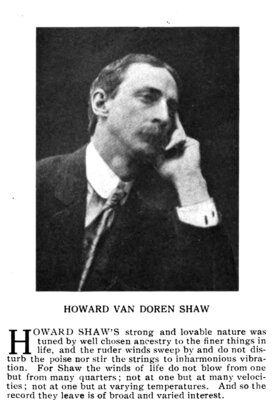

Professional portraits like these showing two home economists in leadership positions of the New York State Federation of Home Bureaus were typical of rising professionals and reflect continued attempts at cultural recognition. Predominantly focused on men, similar stories emphasizing qualifications, technical abilities, and (often) personal ancestry appeared in other professionalizing fields including mathematicians (Abrams 2020a; Abrams 2020b) and architects. In the same year that The Brickbuilder published photographs and plans of the first new home economics building, they also continued their series titled “As He Is Known, Being Brief Sketches of Contemporary Members of the Architectural Profession” (January 1916, Vol. XXV). Mrs. A. E. Brigden, the first President of the NY Home Bureau, presents a stern but measured gaze in her professional portrait. She holds the same expression (somewhat tempered) when amongst the other founders of the NY Home Bureau pictured below front row center seated between Flora Rose and MVR. Notably unlike Beecher and Richards before her, Brigden’s presentation of her professional self in this portrait did not emphasize her gender, but instead paralleled the conventions and assumed status of her male colleagues. Even as home economists remained focused on supposedly “feminine” concerns like kitchens, interior design, fashion, or childcare, these women were not their Victorian predecessors.

In as much as the rise of industrial life transformed domestic ideology and its powerful mythologies in the middle of the nineteenth century, the daily reality of farm life hardly allowed anyone to conceive of women as the “weaker sex.” By the early 1900s rural women running farms alongside their husbands saw little in these ideals that reflected the weariness they felt on a daily basis. Scenes of this idealized American woman’s home, like that enshrined in the frontispiece of the Beecher sister’s 1869 treatise on domestic science, displayed the ease and comfort of the middle-class white family at home. Having already set aside the term domestic science, the new discipline of home economics sought to apply scientific methods to a generation of women who may or may not have aspired to the Beecher’s ideal, but certainly never had time for it on a working farm. Championing the “resolute unsentimentality” of home economists, women’s studies historians and activists Barbara Ehrenreich and Dierdre English explained that:

The architects of domestic science were repelled by the cloying nineteenth-century romanticization of home and womanhood. Lace-bordered images of sweet ‘little’ women placidly awaiting weary breadwinners filled them with revulsion. The home was not a retreat from society, not a haven for personal indulgence; it was just as important as the factory, in fact, it was a factory. […] the scientific home—swept clean of the cobwebs of sentiment, windows opened wide to the light of science—was simply a workplace like any other (For Her Own Good, 1979: 168).

By the early twentieth century, that model of femininity had left the home and been replaced by the figure of the “New Woman.” Ironically, some saw this new womanhood as another source of social unrest. Home economists, on the other hand, embodied, championed, and sought to teach these new standards as a social service. Historian Eric Hobsbawm identifies four primary characteristics of the “new woman”: the public use of cosmetics (attempts to render oneself visually pleasing was a hallmark of sex-work in the 1820s-1880s), public display of body parts, the minimization of secondary sexual characteristics (like having short hair and not emphasizing one’s waist and bust), and a new-found ease of movement both physically and geographically (1989: 217-218). To these, home economists sought to add college-educated, wage-earning, and socially accepted. Nevertheless, while home economists of the early twentieth century seemingly inverted the ideals of nineteenth century femininity, did they center whiteness any less?

Antagonistic to the conventions of Victorian femininity and challenging certain aspects of domestic ideology, home economics emerged as an interdisciplinary profession developed to achieve a “better” society through the proper articulation of its many constituent parts in the science of living. Profession home economists endeavored to identify, describe, evaluate, and codify right living in NYS, the U.S. government, and internationally. They did all of this, to repeat Richards’s words, with the express purpose of “educating and perfecting the ideal human being, the flower of the race for which we are all existing.” Richards unapologetically placed “the race” at the disciplinary heart of home economics from the beginning. Inspired by Galton’s popular eugenics movement, it was even renamed “euthenics” to more accurately reflect its aspirations for a science of daily life aimed at the betterment of the “Race” (Banta 1993). This quote offers a provocative starting place for reconsidering home economics and its engagement with race and racial thinking. Why have historians of home economics mentioned race so sparingly?[3] Dolores Hayden’s accounts of home economics and the professionalization of domestic labor in her book The Grand Domestic Revolution (1995: 150-179) as well as her follow up Redesigning the American Dream (2002: 33-52) have had a tremendous influence on this analysis. However, like Barbara Penner (Dean’s Fellow in the History of Home Economics in 2014), I have come to see that the history of home economics has a far more complex legacy than may first appear from a feminist perspective (May 2018). The body-centered approach they developed over more than half a century has had far reaching effects in U.S. culture; not least in their service to rural farm women across NYS. Home economists and their clients may have been repulsed by the nineteenth century expectations of a woman’s behavior and their role in the home, but it would be irresponsible to ignore those social ideals that were carried forward without analysis and under the guise of technical precision and scientific objectivity. How did the whiteness of femininity and domesticity persist in this new art and science of living? How can a focus on the fashioned body reveal connections between the technical rhetoric of the new managerialism of the early twentieth century and the cultural formation of recognizably professional women? What were the standards of this new womanhood?

[3] Elias’s excellent essay (2006) complicates the history of home economics not so much by revealing as simply acknowledging that in the early twentieth century, MVR and Flora Rose could be considered “model mammas” regardless of their openness about their domestic partnership. And yet, Elias never mentions race once. If Elias substantially nuances the history of home economics by acknowledging the untroubling place of female sexual orientation, it is also worth remembering that she does so without acknowledging race. And so, further, if MVR and Flora Rose are indeed models of womanhood during their tenure at the head of Cornell’s College of Home Economics, to what extent was their whiteness part of the model they disseminated?