Enslaved Labor

The production of cotton and textiles in 19th-century America relied on interregional ties and millions of people of African descent forced into lifelong bondage. The United States became a global exporter of cotton, filling the coffers of southern planters and northern textile manufacturers throughout the century. The exponential economic growth that came with growing and processing raw cotton involved the reproductive exploitation of enslaved women. Consent and rape were not terms applied to the lives of enslaved women in America’s laws. This access to enslaved women’s bodies and labor positioned planters to extract lifelong labor that fueled the national economy of the young nation and made cotton a dominant export.

The North as well as much of Europe held a stake in the cultivation of raw cotton. Northern abolitionists viewed slavery as a moral wrong and evil, while pro-slavery advocates cited the Bible to support the claim that slavery was justified. Despite these theological differences, northern states maintained commercial commitments with planters in the southern states. Northerners sold manufactured goods to Southern planters who focused on the agricultural production of cotton and sugar. Northerners relied upon Southerners to buy textiles, wares, and goods that provided supplies for enslaved laborers and for the plantation household more generally. Northern businessman and abolitionist Lewis Tappan became the founder of antislavery societies throughout the North as well as an important benefactor of the movement. Tappan, however, also maintained business ties with Southern planters in an effort to sell textiles, more specifically “negro cloth” to clothe enslaved laborers. The complex economic relationship between the North and South fell apart as the politics of the antebellum era led to civil war.

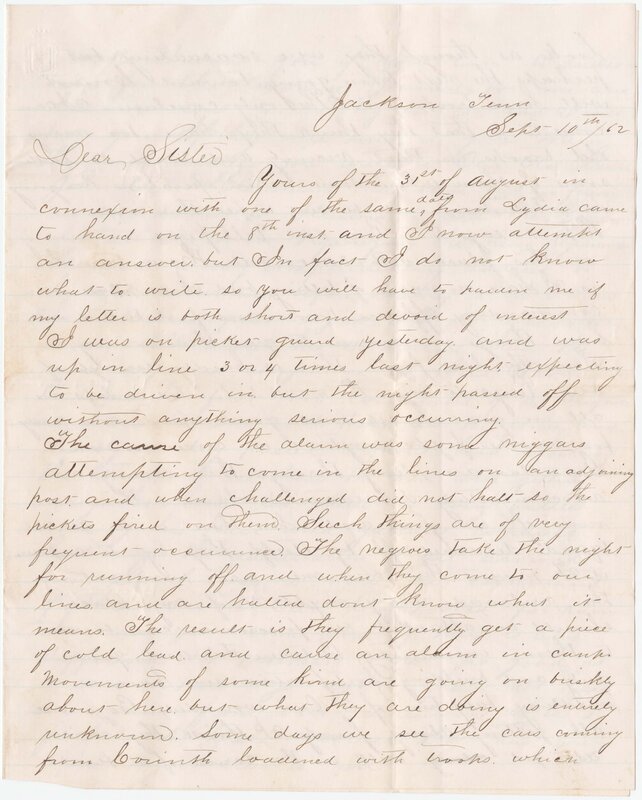

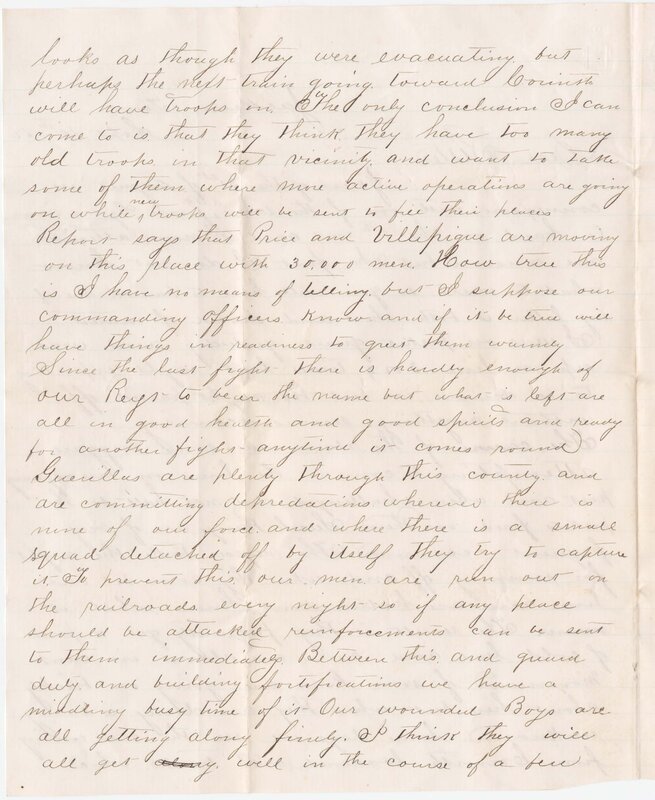

During the Civil War, enslaved people continued to produce cotton throughout the South, and the Confederacy hoped to secure enough military victories to attract European investment. Leaders of the Confederacy viewed themselves as a sovereign and independent nation of slaveholding states and pursued avenues to recover losses from the severed economic ties with the North. As the war raged on, some enslaved people escaped to Union lines and soldiers included accounts of these encounters in letters to family. When formerly enslaved people became free, they used their skilled labor to leverage their own economic futures. In the South, enslaved women learned to sew a range of garments that included the plain and shapeless uniform assigned to enslaved laborers as well as the intricate garments that white planters, mistresses, and their children wore for formal occasions. Slave owners maximized the use of enslaved women’s sewing skills to produce anything that might need to be sewn, mended, or altered. After the war, formerly enslaved women forced to work in the cotton fields and sew garments were no longer required to wear linsey “negro cloth,” but instead found creative ways to fashion themselves after emancipation.

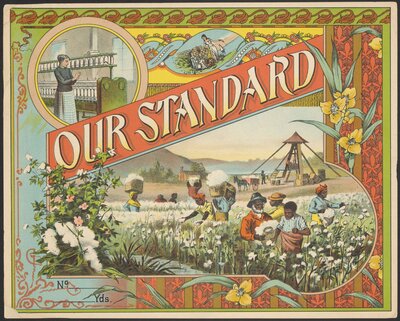

Unknown artist. Our Standard, Cloth Label, ca. 1800s.

A cloth label that would have been affixed to the bolts of cotton fabric that came from the mills shows the source of the labor that produced the raw cotton - enslaved people on Southern plantations. It also portrays the final production of that cotton by white female laborers in Northern mills. The use of images of enslaved labor in advertising and publicity materials was not uncommon, well into the 20th century.

On loan from the Kheel Center for Labor-Management Documentation & Archives

Collection/Call #: 6524/003 MB

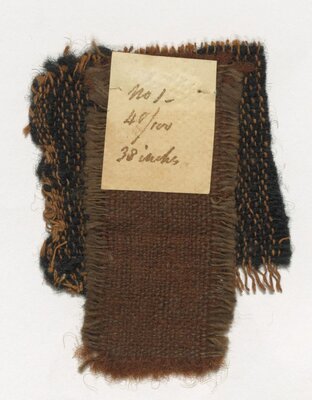

Ware Manufacturing Company. Sample of “negro cloth,” November 1826.

On loan from the Kheel Center for Labor-Management Documentation & Archives

Collection/Call #: 6935

Search CUL catalog for this item/collection

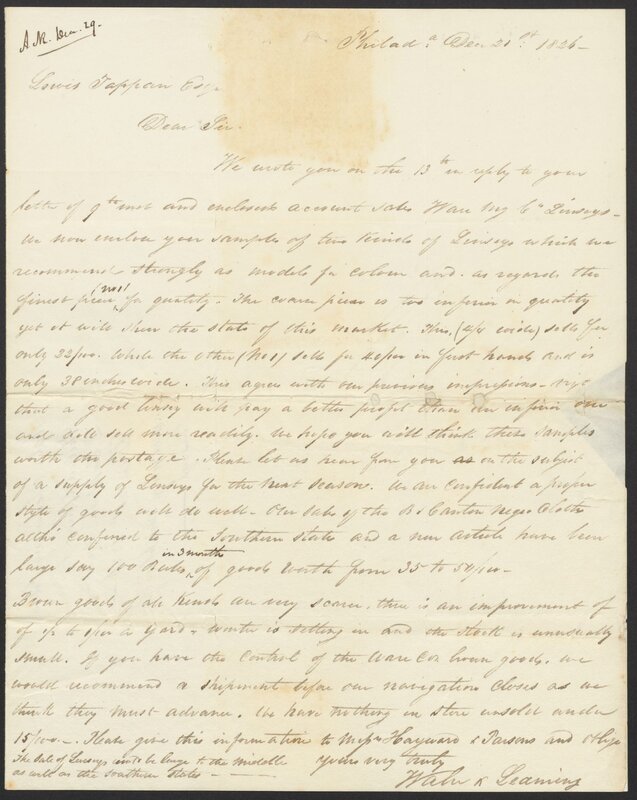

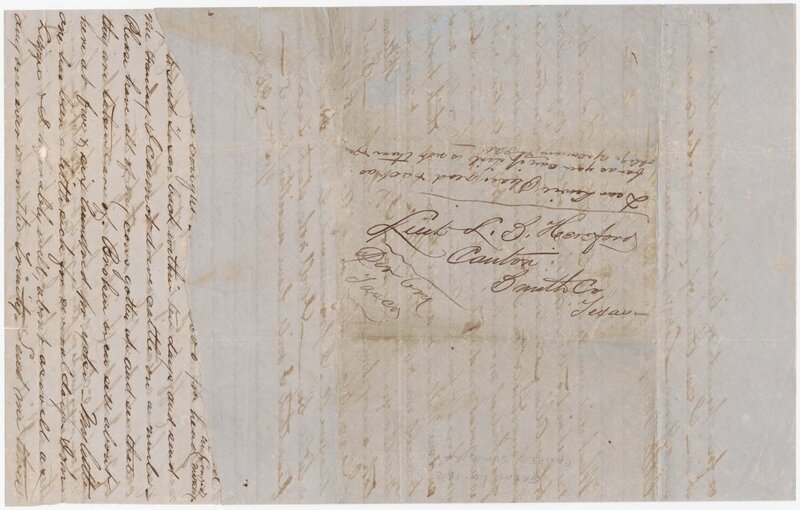

Ware Manufacturing Company. Letter to Tappan from Waln & Leaming, November 1826.

The "negro cloth" swatches displayed above were sent to Lewis Tappen along with the note, “Our sales of the B. Canton negro cloth altho confined to the Southern States and a new article have been large, say 100 Bales in 3 months of goods worth from 35 to 37/100.”

On loan from the Kheel Center for Labor-Management Documentation & Archives

Collection/Call #: 6935

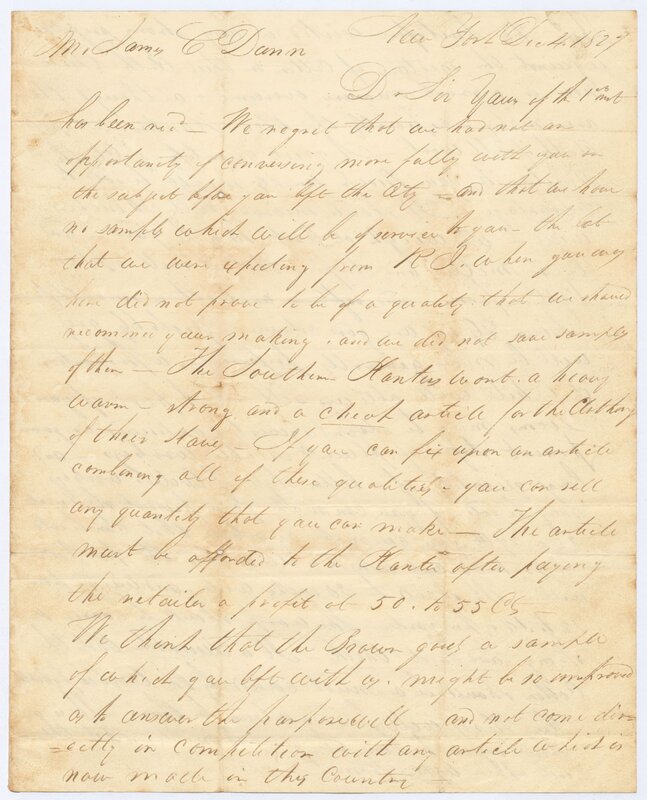

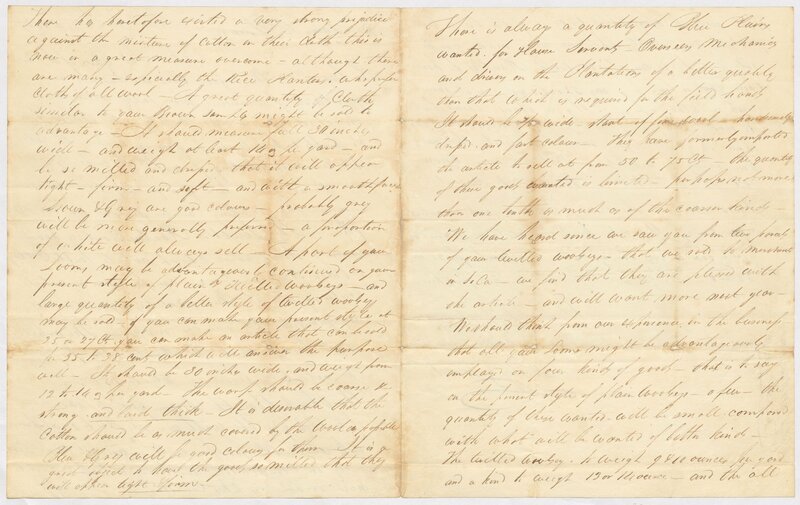

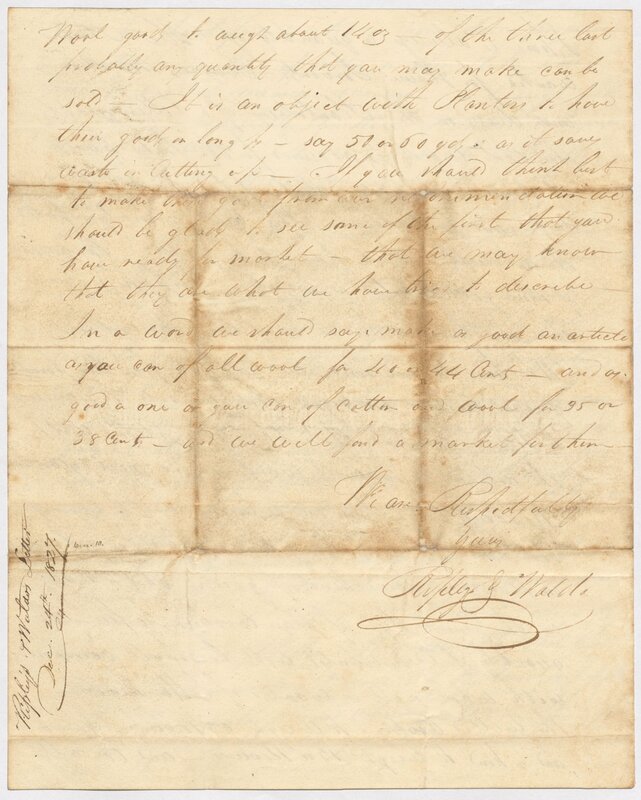

Ripley & Waldo. Correspondence to Dunne of Ware Manufacturing Company from Ripley & Waldo, a sales agent, December 4, 1827. In this letter Ripley & Waldo discuss, among other things, the different colors of fabric needed for the different roles of enslaved people on the plantation.

On loan from the Kheel Center for Labor-Management Documentation & Archives

Collection/Call #: 6935

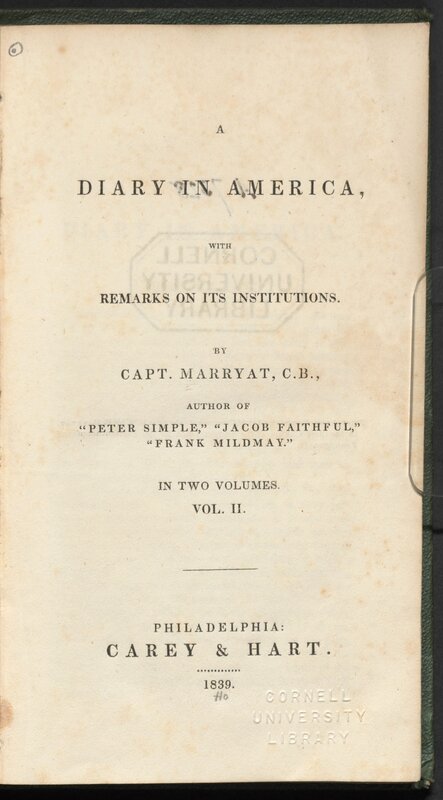

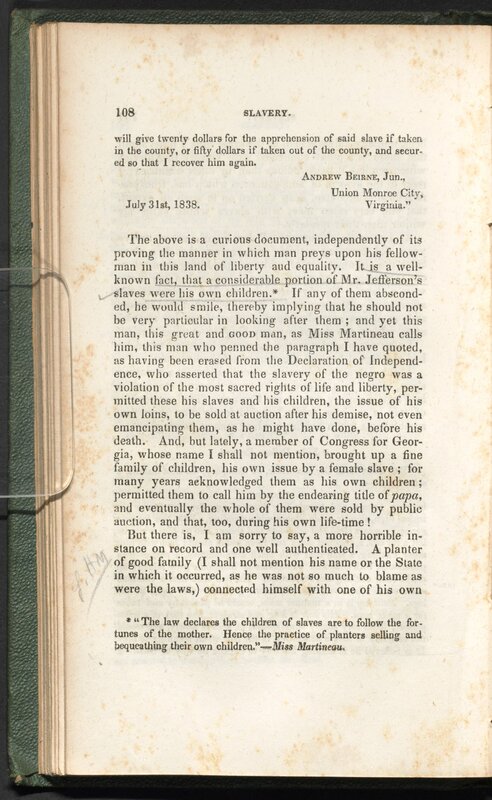

Frederick Marryat. A Diary in America, 1839.

Marryat explains that the young nation’s leading figures, such as Thomas Jefferson and a number of other politicians, owned children they had with enslaved women.

Collection/Call #: Rare Books E165 .M36 1839

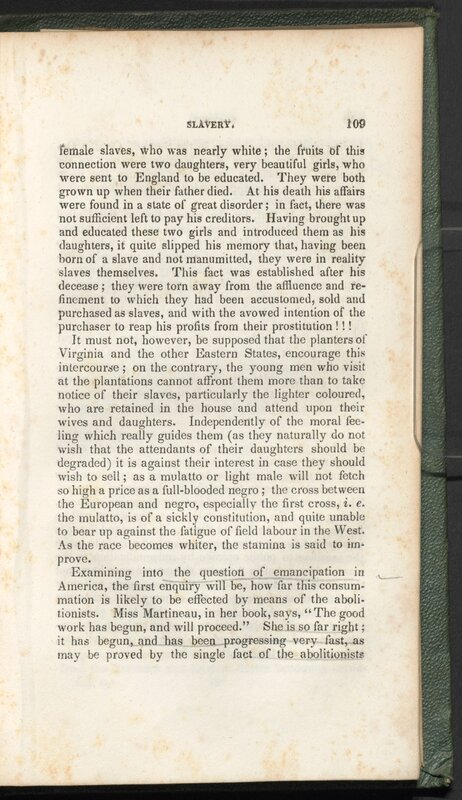

David Christy. Cotton is King: or the Culture of Cotton, and its Relation to Agriculture, Manufactures and Commerce; to the Colored People; and to Those Who Hold That Slavery is in Itself Sinful, 1855.

Christy argued that immediate abolition remained an impossibility because of the moral inferiority of people of African descent and the global dependence on cotton. He referred to the abolitionist movement as “fruitless warfare” and championed the colonization movement, which focused on the relocation of free Black people.

Collection/Call #: Rare Books E449 .C55

E. N. Elliott (Editor). Cotton is King, and Pro-Slavery Arguments: Comprising the Writings of Hammond, Harper, Christy, Stringfellow, Hodge, Bledsoe, and Cartwright, on This Important Subject, 1860.

The author made four key points: that God sanctioned slavery, that the United States protected slavery in the Constitution, that the law recognized slavery, and that slavery as a southern practice should be characterized as one “full of mercy.”

Collection/Call #: Rare Books E449 .E46

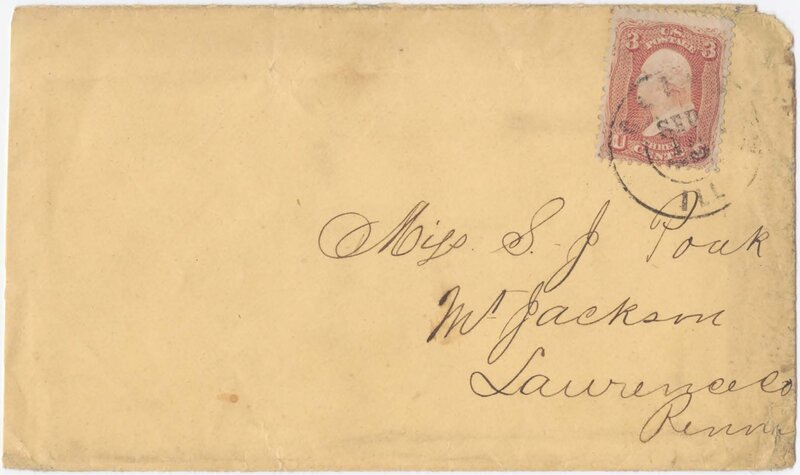

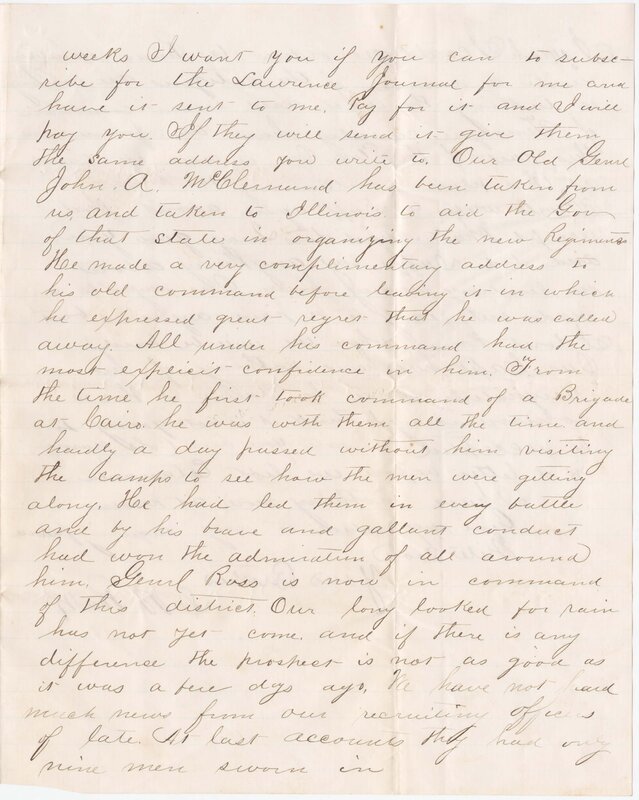

David W. Poak. A letter describing slaves crossing lines at night and getting a "piece of cold lead,” 1862.

Collection/Call #: 4681

Thomas Falconer. Thomas Falconer cotton plantation account book, with journal of slave financial accounts and family records, ca. 1861.

In ledgers such as this, planters recorded details about the weather, the supplies used, and the work that enslaved laborers performed every day. These account books serve as a testament to the extensive and exploitative enterprise of cotton agriculture.

Collection/Call #: 4681

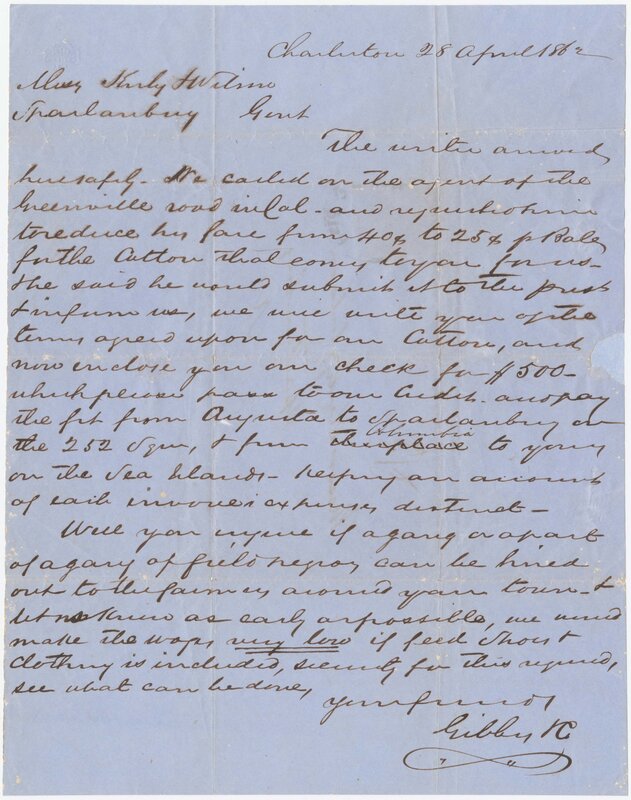

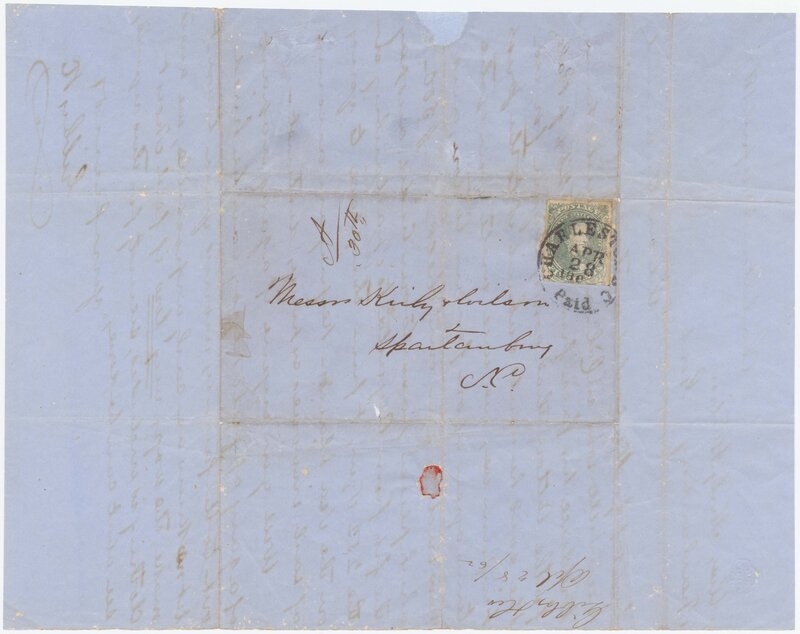

Gibbs and Co. Pricing of cotton and hiring field hands at low wages, 1862.

Collection/Call #: 4681

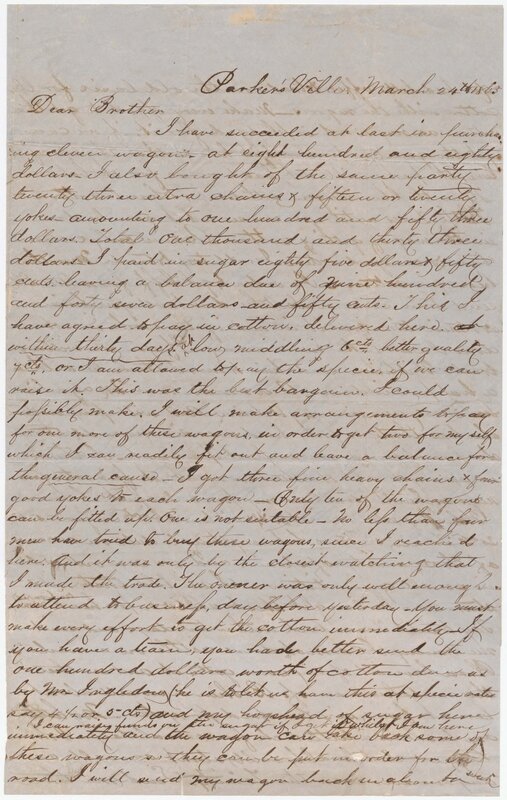

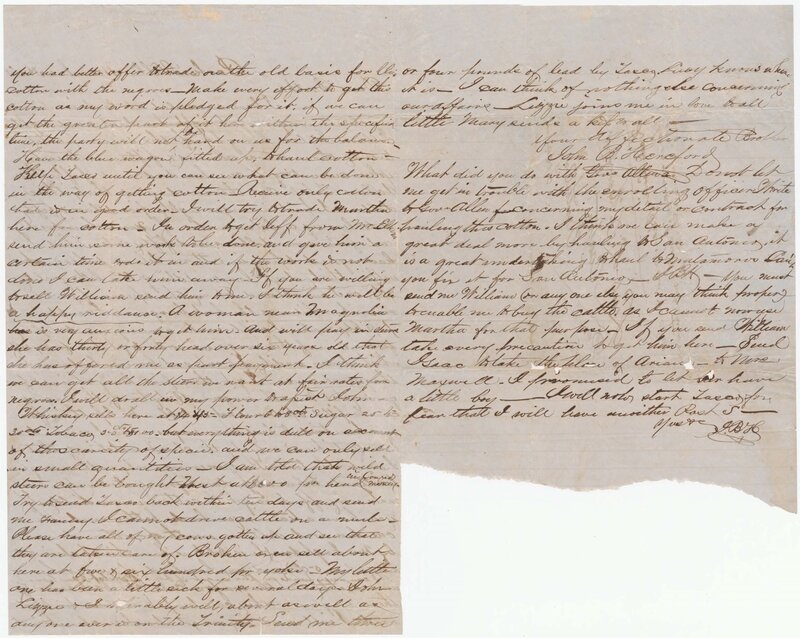

Unknown correspondent. Slavery Letter, regarding trading men for cattle and cotton, 1865.

Collection/Call #: 4681

Unknown photographer. Marguerite, ca. 1880

Formerly enslaved women such as Marguerite reveal the ways that Black women fashioned themselves after emancipation. This hand-colored tintype shows the intricate features such as the variation in plaid or cross-barred pattern, the cascading layers of the skirt, and the detailed neckline and sleeves. The powerful gaze, the hand firmly anchored at the hip, offers a striking view of her sartorial personality.

Collection/Call #: 8043

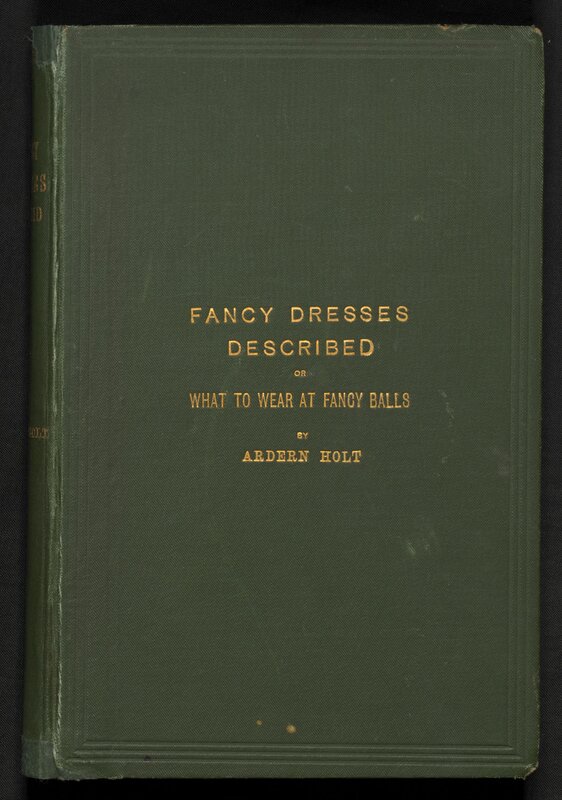

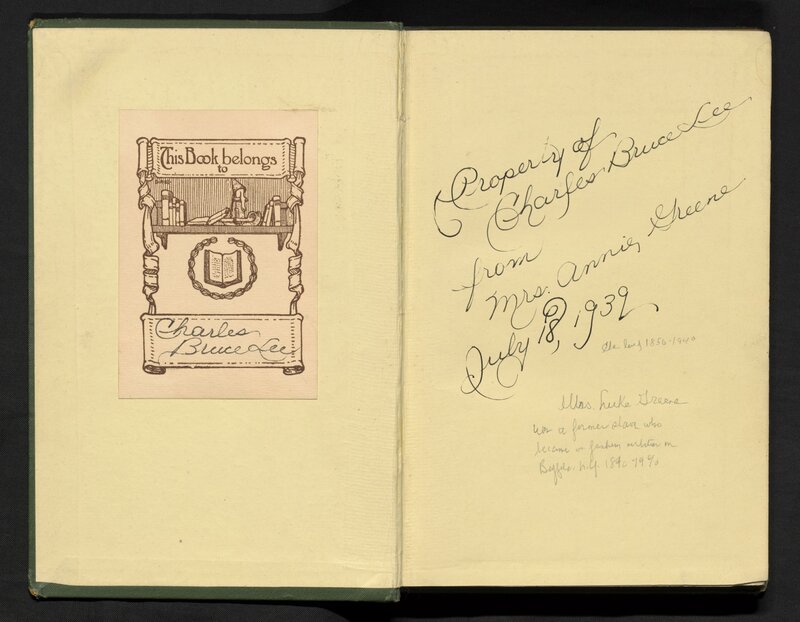

Ardern Holt. Inscription and facsimile illustration of the “Hornet” dress, Fancy Dresses Described: or, What to Wear at Fancy Balls, 1884.

This copy was originally owned by a formerly enslaved woman, Mrs. Annie Greene, who, according to the inscription, became a fashion writer in Buffalo, New York, from 1890-1940. As most enslaved women were forbidden to read or own a book, Greene likely treasured this source, as it gave her not only access to vibrant illustrations and descriptions, but inspiration that drove her own economic mobility.

Collection/Call #: GT1750.H65 F36 1884