Landscape

And what of the people who had first named the landscape? By the time of the Industrial Revolution, nations like the Abenaki, Pennacook, Pequot, Mohegan, Narragansett, and Wampanoag had been displaced, enslaved, or killed by colonizers’ diseases. In 1616, a little over 400 years before our current pandemic, an epidemic caused by Europeans killed an estimated 75% of the indigenous people living in New England coastal areas. This is the forgotten context of the first Thanksgiving in 1620.

The landscape of the South was similarly affected. Whitney's cotton gin and the resulting industrialization of cotton textile manufacturing required increasing amounts of land. Cotton pushed the expulsion of indigenous peoples as the U.S. expanded westward. Here, nations such as the Chickasaw, Choctaw, Creek, Cherokee, and Seminole would also be decimated by war and disease, and ultimately death-marched to lands even farther west on the “Trail of Tears.” What often goes undiscussed is that this move was directly related to the need for more land on which to grow cotton.

In turn, this crop and the growth of industrial textile manufacturing supported the use of slave labor in the South for generations. The first 20 enslaved Africans set foot on British American soil in 1619. An estimated 10 million people were enslaved over the next 246 years. By the end of the Civil War, there were an approximately 3.5 million enslaved people in the U.S. Beginning in the 19th century, the financial strength of the U.S. was directly tied to the textile and garment industries and the use of slave labor on indigenous land.

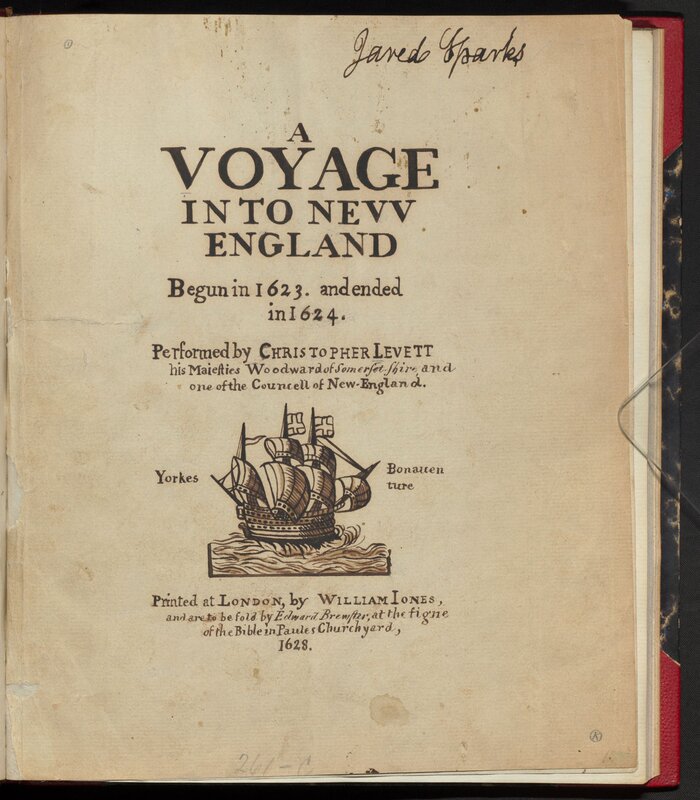

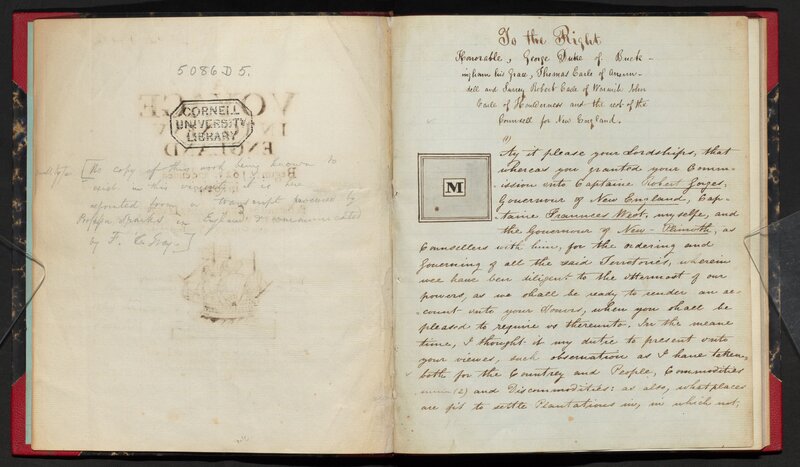

Christopher Levett. A Voyage into New England, Begun in 1623, and Ended in 1624, [1800s].

Account of a visit to New England by an Englishman, consisting mainly of resources that can be extracted from the land or areas that can be used to create “plantations” – agriculture for profit. In a description of the current day York River, he mentions that land has been cleared and planted by indigenous people “who are all dead,” and thus is ideal for incoming settlers.

Collection/Call #: Archives 4600 Bd. Ms. 102

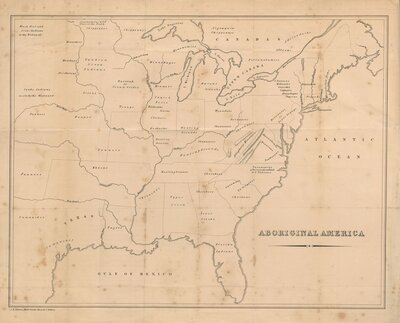

Frederick Marryat. A Diary in America v. 2, “Aboriginal Map of America,” 1839.

Colonists landed on a continent that was populated by millions of indigenous people living in hundreds of communities and nations. While the 1839 map confines a few of those communities within the boundaries of the United States, the overlay imagines what those original communities might have looked like and challenges our perspective of boundaries, ownership, and the value of land. [For a more accurate view of original indigenous communities, visit Native Land Digital's comprehensive map.]

Collection/Call #: Rare Books E165 .M36 1839

Essex Company. Volume of Flowage Map, ca. 1868.

Map showing the flowage of the Merrimack in a time when the current was used to power the turbines that powered the mills. The Essex Company charged its customers for that power and was one of the most powerful companies of its time.

On loan from the Kheel Center for Labor-Management Documentation & Archives

Collection/Call #: 6633

Search CUL catalog for this item/collection

Matthew Brown Hammond. “Map showing the relation existing between Slave Labor and Cotton Production,” in The Cotton Industry, an Essay in American Economic History. Part I, The Cotton Culture and the Cotton Trade, 1897.

Collection/Call #: Rare Books arW13008 no.1

Philadelphia Museum (Publisher). Cotton Market, ca. 1900-1920.

On loan from the Kheel Center for Labor-Management Documentation & Archives

Collection/Call #: 6984 P

Search CUL catalog for this item/collection

George Russell. "Miles of Mills" Merrimack River, Lowell, Massachusetts, 1918.

When this photo is viewed in comparison with the Hillsborough Woolen Mill daguerreotype, we see how much industrialization has changed the landscape in the intervening 70 years.

On loan from the Kheel Center for Labor-Management Documentation & Archives

Collection/Call #: 6724 P

Unknown photographer. Image of the hydroelectric plant at Massachusetts Mills, 1919.

On loan from the Kheel Center for Labor-Management Documentation & Archives

Collection/Call #: 6524/002 P

Search CUL catalog for this item/collection

Unknown photographer. Area of future dam, Dummer, New Hampshire, 1921.

On loan from the Kheel Center for Labor-Management Documentation & Archives

Collection/Call #: 6524/002 P

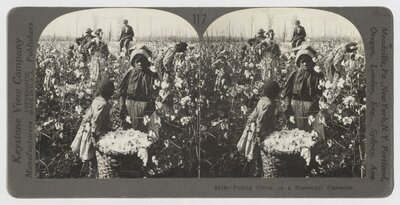

Keystone View Company (Publisher). Cotton Picking, ca. 1900-1920.

An image of Black children picking cotton, meant for entertainment viewing using a stereoscope, undercuts the reality of life in the Jim Crow South, in which many Blacks were sharecroppers and circumstances had not changed much since emancipation.

On loan from the Kheel Center for Labor-Management Documentation & Archives

Collection/Call #: 6524/002 P