Female Labor

Women were seen as ideally suited to work in the early textile industry in the United States. They were associated with the domestic arts of weaving, darning, and sewing. They could be paid half of what their male counterparts made. And, it was thought, they could be controlled. For their part, women left their families by the score for opportunities that lay beyond the home, paving the way for generations of women that would follow.

To combat the fear of the corrupting influence of industrialization and to encourage parents to send their daughters to the mills, communities were created to promote moral protection for women. Women’s lives were tightly controlled by the mills, and by the mill-owned boarding houses where they lived. They were encouraged to take up hobbies, like writing for mill-owned newsletters. The most famous of these newsletters was the Lowell Offering, which included articles, stories, songs, and poetry written by women millworkers. It offered an outlet for the creative and intelligent thoughts of working women, but it was also used as propaganda that the paternalistic mill system worked.

Sarah Bagley started writing for the Offering in 1840, and soon, she, like other millworkers, began advocating for shorter days and better pay. She went on to write for, and eventually edit, the Voice of Industry, a newspaper that pressed for better working conditions and worker solidarity. Seeing this as a challenge to their authority by “radicals of the worst sort,” mill owners fought back against worker organization by blacklisting women like Bagley and anyone associated with them. Mill owners also hired new waves of immigrants as a means of breaking that solidarity.

Despite these attempts at division, the immigrants would soon press for change in the form of organized labor and unions. Yet women often found themselves on the outside of unionization efforts, which were largely led by men. Though women comprised the majority of the workforce, they rarely held power within the unions. Black, Asian, and Latina women had an even more difficult time and did not see themselves reflected in union leadership or membership. It was well into the 20th century before things slowly began to change, as the demographics within the industry pushed for representation. Despite these gains here in the U.S., 80% of the garment industry workforce today consists of women from some of the world’s poorest countries. Like their counterparts over a century and a half ago, these women face harassment and intimidation as they continue to organize and fight to improve their working conditions.

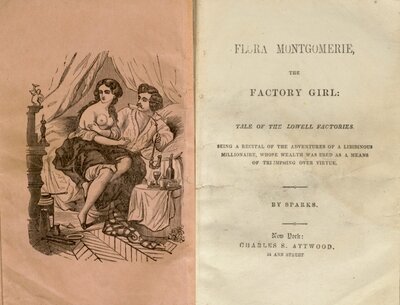

William Hogarth. “In Bridewell Beating Hemp with Many Others in the Like Circumstances,” ca. 1770.

Plate 4 of “A Harlot’s Progress,” a series of six engravings made by Hogarth showing the rise and eventual fall of a woman named Polly (or Molly). Although she arrives in London seeking employment as a seamstress, she is misled into a life of prostitution by Elizabeth Needham, a well-known Madam of the time. Polly eventually dies of syphilis. In the scene in this engraving, Polly has been sent to Bridewell prison and is beating hemp. Like Flora Montgomerie, these stories were used to warn women against the fate that awaited them if they wandered too far astray.

On loan from the Kheel Center for Labor-Management Documentation & Archives

Collection/Call #: 6524/004 G

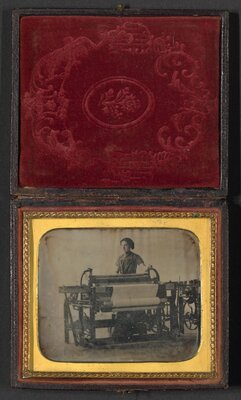

Unknown photographer. A woman at a power loom, ca. 1848-1852.

On loan from the Kheel Center for Labor-Management Documentation & Archives

Collection/Call #: 6524/002P

Search CUL catalog for this item/collection

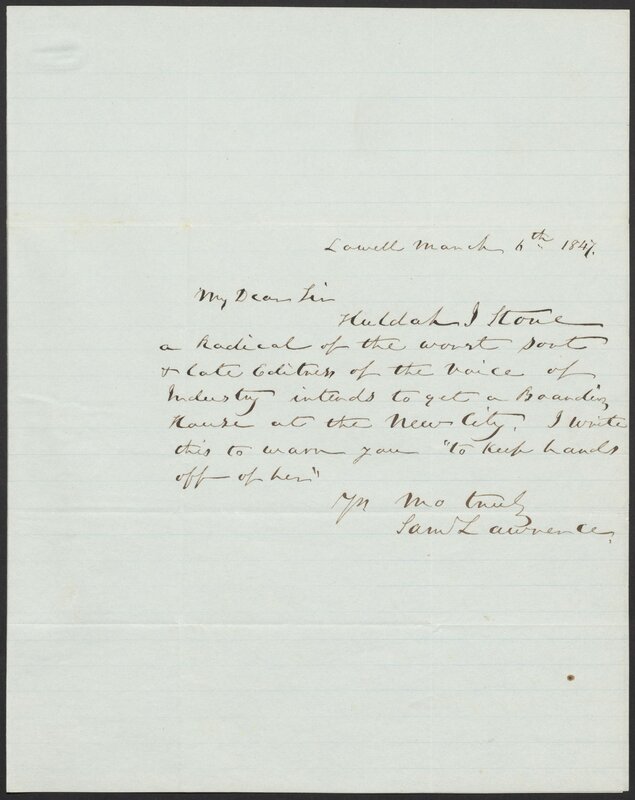

Samuel Lawrence. Letter from Samuel Lawrence to Storrow warning about Huldah Stone, March 6, 1847.

Huldah Stone was a known associate of the labor reformer Sarah Bagley. In this letter, Lawrence refers to her as “a radical of the worst sort” and warns Storrow that she is seeking a room in a boarding house nearby.

On loan from the Kheel Center for Labor-Management Documentation & Archives

Collection/Call #: 6633

On loan from the Kheel Center for Labor-Management Documentation & Archives

Collection/Call #: PZ3 .S6 [185?]

Unknown photographer. Mary D. Warner, ca. 1854.

A slip of paper in the case identifies her as: "Mary D. Warner, taken about 1854." We can tell Mary was a mill worker based on the shuttle in her hands. Images like this were fairly common for the time, as many mill workers would proudly sit for portraits that demonstrated their new economic mobility.

On loan from the Kheel Center for Labor-Management Documentation & Archives

Collection/Call #: 6524/002P

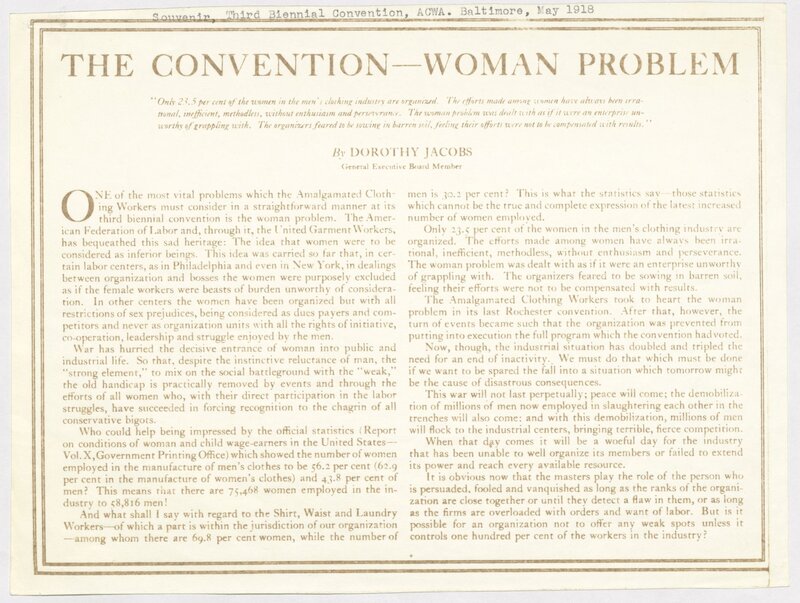

ACWA. "Woman Problem," May 1918.

A printed copy of Dorothy Jacobs’s speech before the third biennial Convention of the Amalgamated Clothing Workers of America, in which she points to the lack of representation of women within the union despite their making up the majority of garment workers.

On loan from the Kheel Center for Labor-Management Documentation & Archives

Collection/Call #: 5619

Unknown photographer. Photograph of a "puffer," ca. 1918.

On loan from the Kheel Center for Labor-Management Documentation & Archives

Collection/Call #: 5619 P

Women’s Bureau, United States Department of Labor. “The Negro Woman Worker,” Bulletin no. 115, Women at Work, 1933.

Black women came to the North in the millions as part of the Great Migration, and many found work in garment shops. As this booklet states, “hardships have fallen with doubled severity” on Black workers, who were often relegated to the lowest paying jobs and not well supported by organized labor.

On loan from the Kheel Center for Labor-Management Documentation & Archives

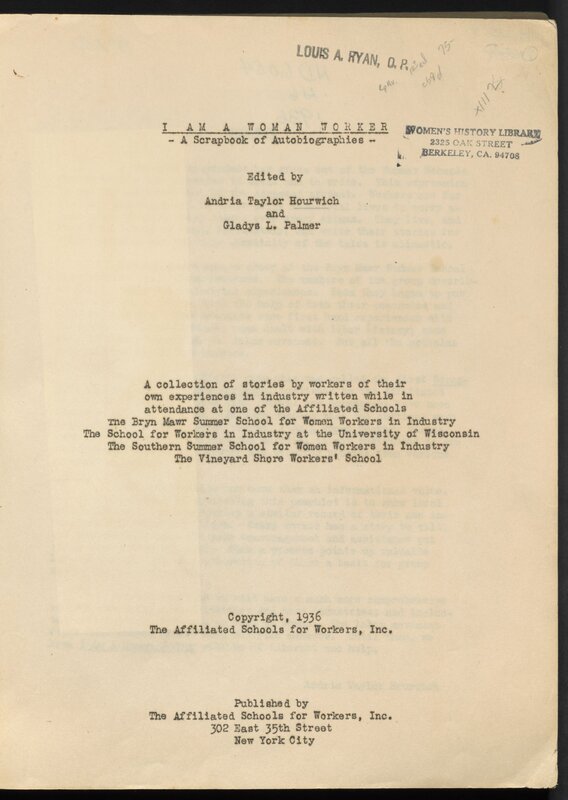

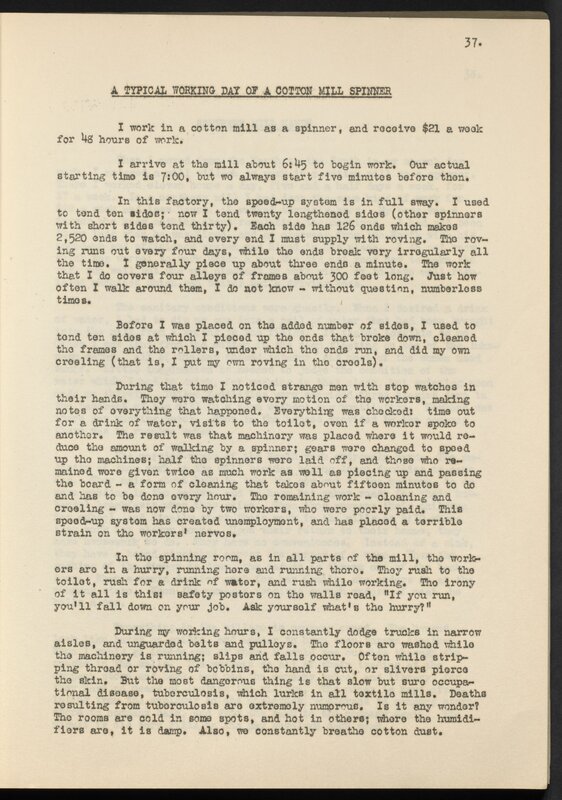

The Affiliated Schools of Workers, Inc. “A Typical Working Day of a Cotton Mills Spinner,” in I am a Woman Worker: A Scrapbook of Autobiographies, 1936.

On loan from the Kheel Center for Labor-Management Documentation & Archives

Collection/Call #: HD6054 H6 1936

ACWA. Viva La Huelga flyer, ca. 1972-1974.

By the 1970s, many Spanish-speaking immigrants had found work in the textile industry in the U.S. They still make up a large part of the workforce in what remains of the garment industry here today.

On loan from the Kheel Center for Labor-Management Documentation & Archives

Collection/Call #: 6524/004 G

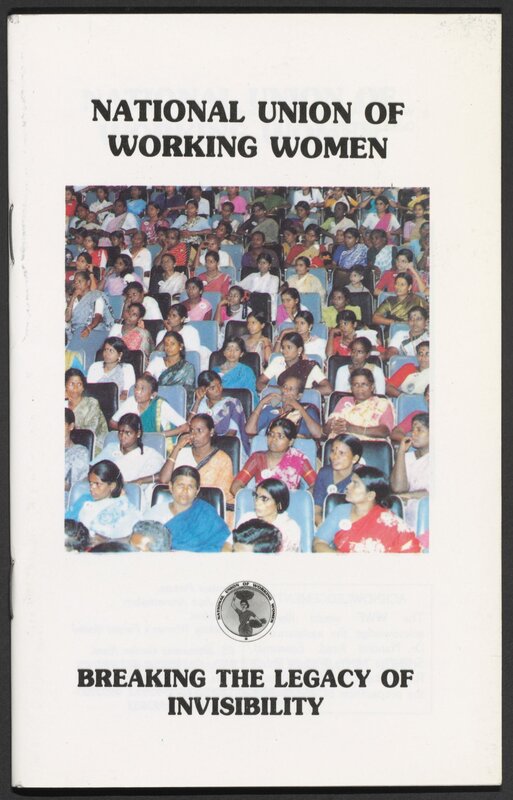

National Union of Working Women. National Union of Working Women: Breaking the Legacy of Invisibility, October 1995.

On loan from the Kheel Center for Labor-Management Documentation & Archives

Collection/Call #: 6000/027 PUBS