Incarcerated Labor

Incarcerated workers lack basic rights that many workers take for granted. In 1993, federal courts held that they are not “employees” under the Fair Labor Standards Act, stripping them of protections concerning wages and overtime pay. The highest-paid state prisoners make a maximum of $1.15 an hour, and some make nothing at all. Further, OSHA standards for safe and healthy workplaces do not apply; nor do the National Labor Relations Act-protected rights to unionize and engage in collective bargaining. The lack of federal regulation trickles down to the states, creating an inconsistent, broadly unprotected system of labor.

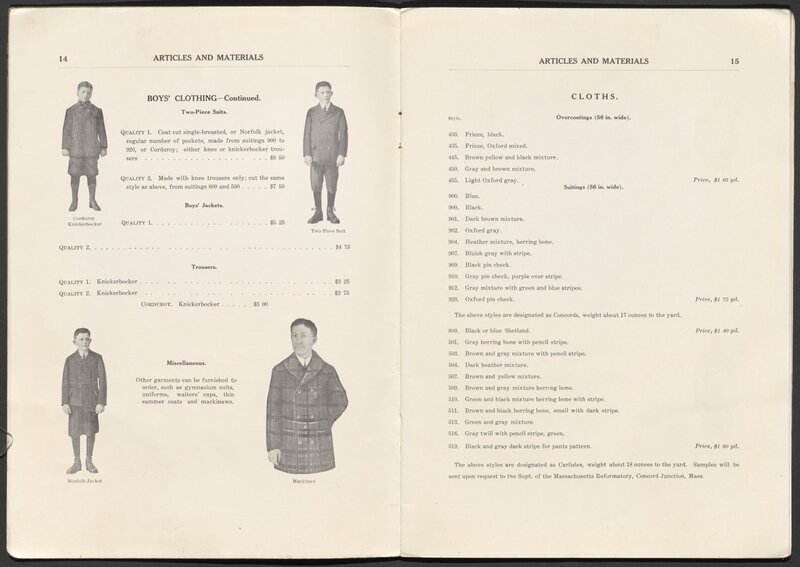

Many industries have benefited from the use of imprisoned labor. Historically, the textile industry has been one of the main recipients of such labor; in the 1930s, it was the first industry to be incorporated into the federal penal labor system. Incarcerated textile workers produce(d) a wide range of textiles, including clothing ranging from military and police uniforms to consumer goods. Though the strength of the textile industry began dwindling in the 1970s, imprisoned workers continue to produce garments and textiles for state and, in some cases, private use.

The 13th Amendment left the door open for involuntary servitude as punishment for crime, and while some argue that prison labor is “voluntary,” the relationship between incarcerated employee and employer is inherently exploitative. This power imbalance falls heavily on already marginalized communities. From the 1860s Black Codes to the 1970s war on drugs, the formal abolition of slavery immediately led to new forms of over-policing racial minorities, with the result that Black and Latinx populations are now overrepresented in the prison system. While prison industries tout these programs as training for life after prison, the data doesn’t always support that. Upon release, job applications asking about criminal records, barriers to acquiring professional licenses, and policies that fully bar ex-convicts' employment make societal reintegration difficult. With little to no savings and diminished job prospects, many formerly incarcerated individuals end up back in the system, where the cycle begins anew.

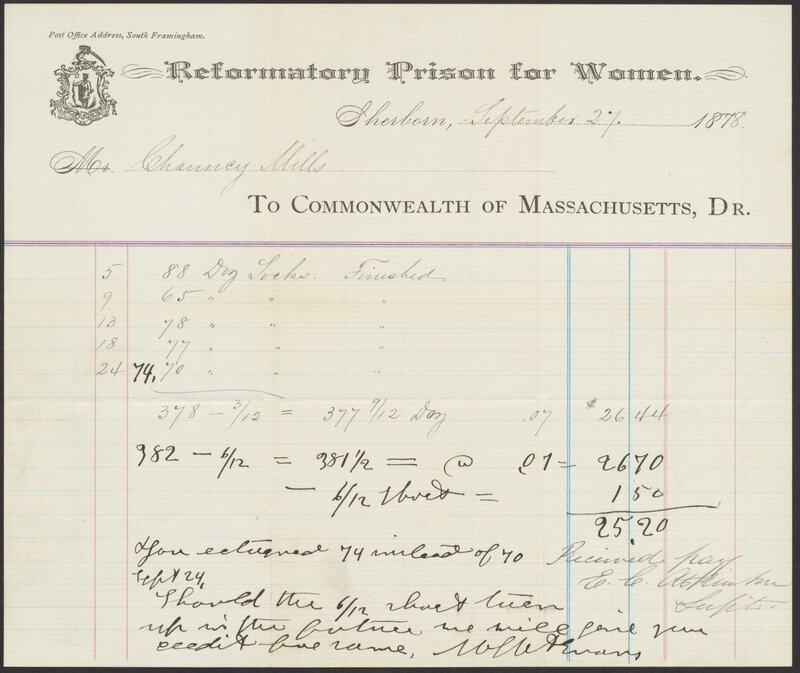

Massachusetts Reformatory for Women. Receipts of prison labor for sewing socks, 1878.

A receipt, addressed to Chauncy Mills, for the sewing of socks at the Massachusetts Reformatory for Women. The reformatory opened in 1877 as part of a broader trend toward building prison facilities specifically for women.

On loan from the Kheel Center for Labor-Management Documentation & Archives

Collection/Call #: 6550

Walnut Street Prison. Manufactured at the Philadelphia Penitentiary, 1800-1820.

This cloth label depicts the first penitentiary in the U.S., which operated from 1773 to 1838. The emergence of penitentiaries as places where imprisoned people could reflect and repent, as opposed to the primary objective of punishment, was largely driven by the Quaker community.

On loan from the Kheel Center for Labor-Management Documentation & Archives

Collection/Call #: 6524/003 MB

Search CUL catalog for this item/collection

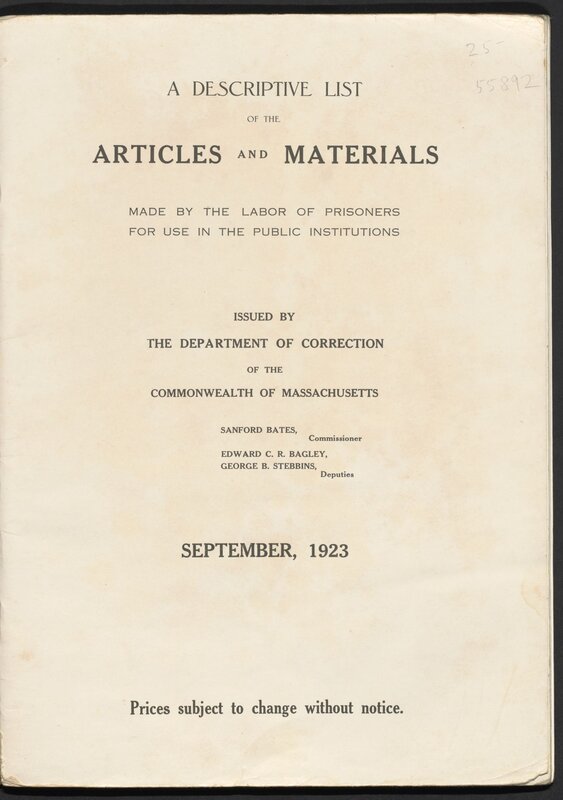

Department of Correction of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. A Descriptive List of the Articles and Materials Made by the Labor of Prisoners for use in the Public Institutions, 1923.

On loan from the Kheel Center for Labor-Management Documentation & Archives

Collection/Call #: HV8925 M3D4 1923

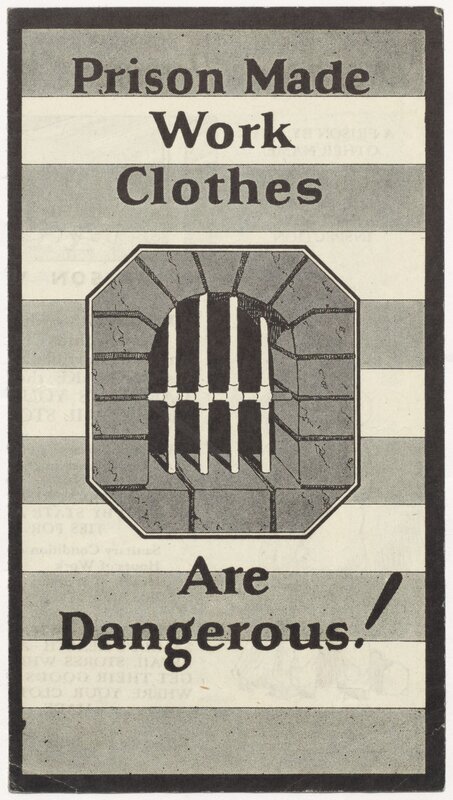

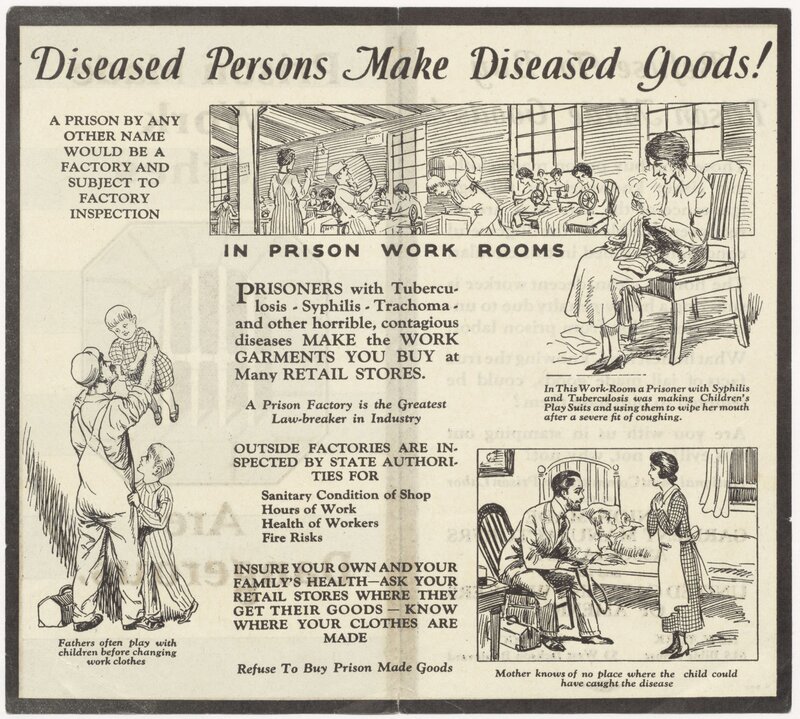

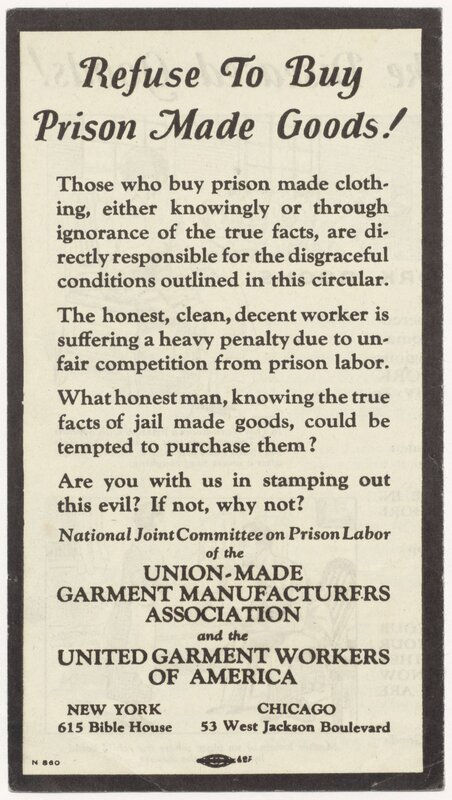

National Joint Committee on Prison Labor of the Union-Made Garment Manufacturers Association and the United Garment Workers of America. Prison Made Work Clothes are Dangerous, 1925.

Pamphlet calling for a boycott of clothes made through imprisoned labor. It shows that union opposition to imprisoned labor was not always based on ethics, often focusing on the aspect of free competition instead.

On loan from the Kheel Center for Labor-Management Documentation & Archives

Sidney Hillman. Telegraph to FDR regarding Sumners-Ashurst Prison Labor Bill S.2904, July 22, 1935.

The bill prevented states from selling goods made with imprisoned labor across state lines. Sidney Hillman, prominent labor leader and head of the Amalgamated Clothing Workers of America (ACWA), supported it, claiming that it would work in favor of cotton garment industry employers and workers. The bill was eventually enacted as the Ashurst-Sumners Act of 1935.

On loan from the Kheel Center for Labor-Management Documentation & Archives

Collection/Call #: 5619

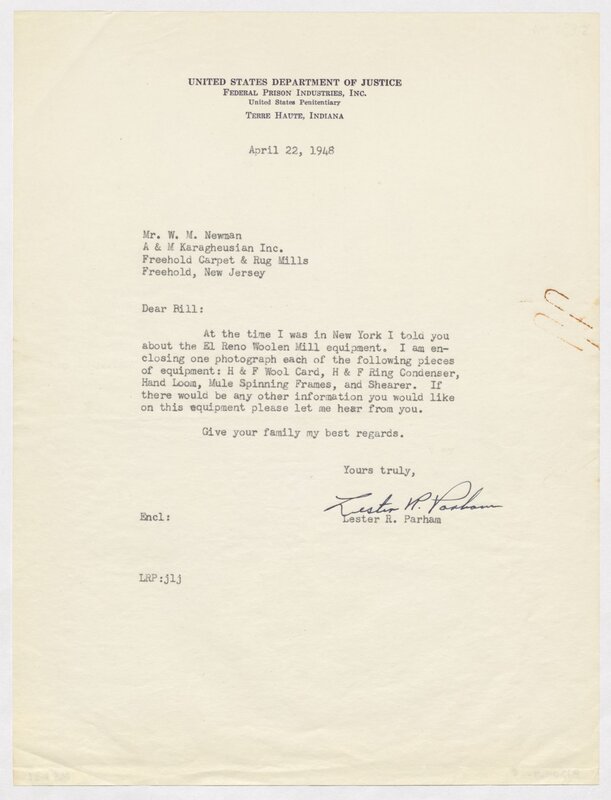

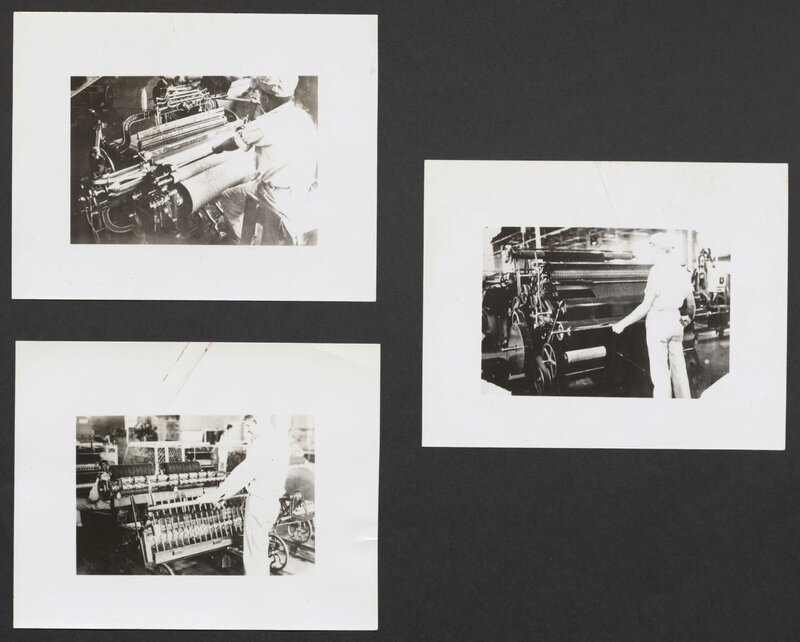

Lester R. Parham. Letter and three photographs, 1948.

The workers in the background of these photographs were an unintended addition, as the photos were meant to display the woolen mill equipment. Inadvertently, they give us a glimpse into the lives of workers at the El Reno Woolen Mill.

On loan from the Kheel Center for Labor-Management Documentation & Archives

Collection/Call #: 6648

Bryon F. Cook. Notebooks on textile manufacturing at Green Haven Prison, Stormville, New York, 1957.

On loan from the Kheel Center for Labor-Management Documentation & Archives

Collection/Call #: 6548

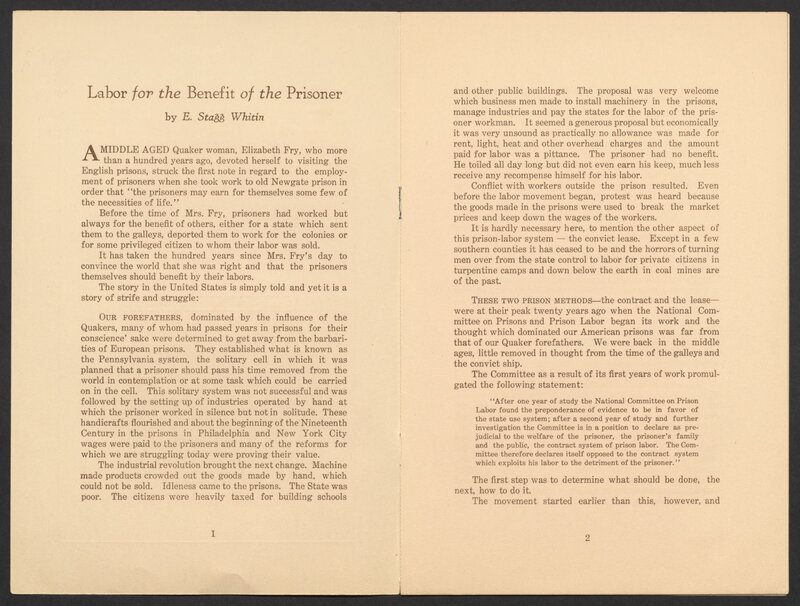

E. Stagg Whitin. Labor for the Benefit of the Prisoner, 1930.

Collection/Call #: Rare Books HV8899 .W59 1930

Lester R. Parham. Letter and three photographs, 1948.

The workers in the background of these photographs were an unintended addition, as the photos were meant to display the woolen mill equipment. Inadvertently, they give us a glimpse into the lives of workers at the El Reno Woolen Mill.

On loan from the Kheel Center for Labor-Management Documentation & Archives

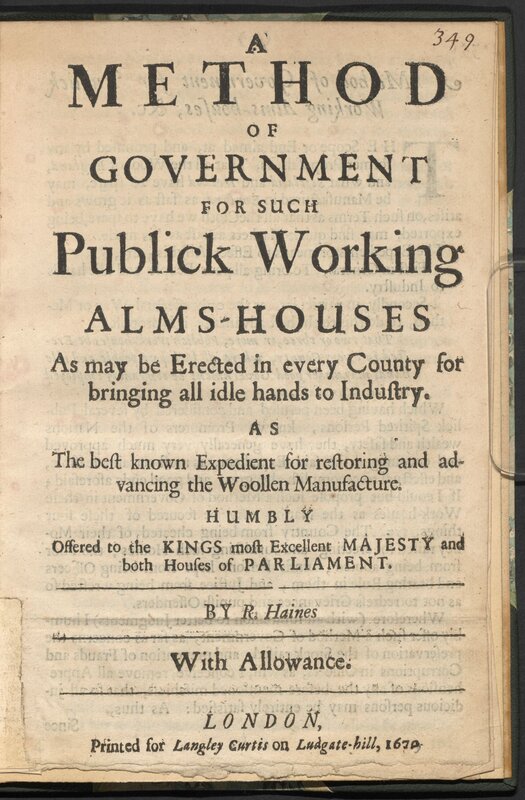

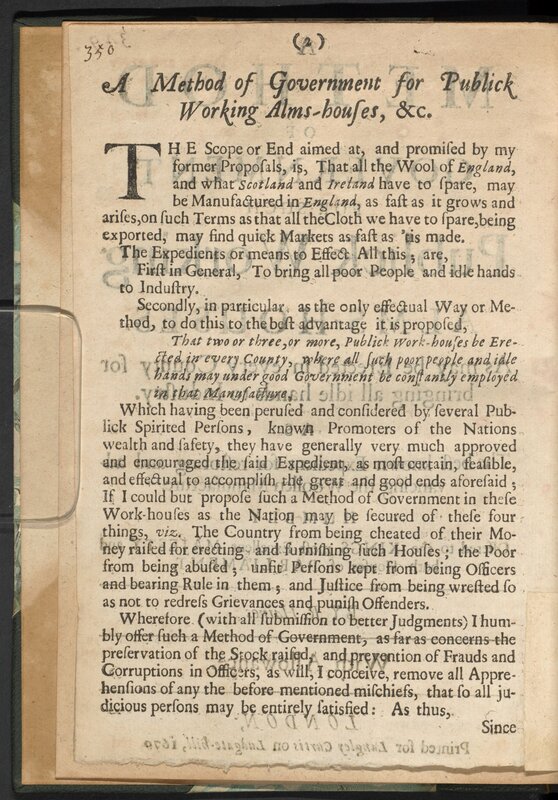

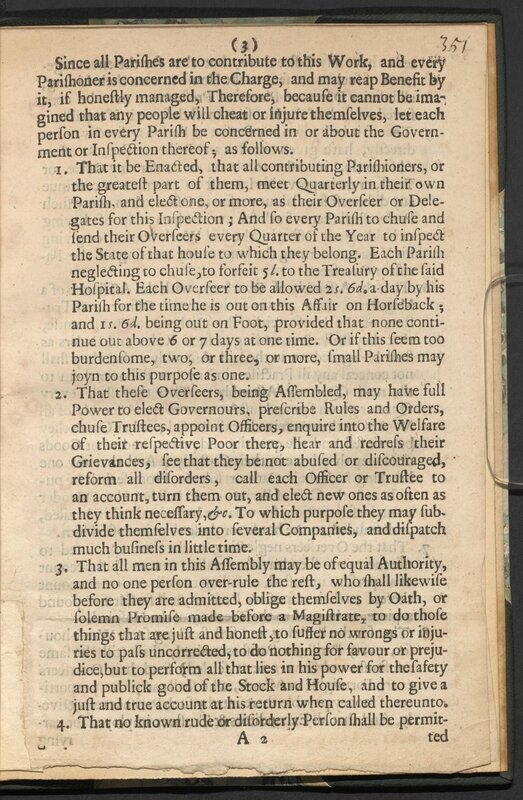

Richard Haines. A Method of Government for such Publick Working Alms-houses as may be Erected in Every Country for Bringing all Idle Hands to Industry. As the Best Known Expedient for Restoring and Advancing the Woollen Manufacture, 1679.

The use of imprisoned labor predates industrialization. Often incarcerated for no other reason than being poor, people were pulled from the workhouse for labor in the British woolen industry.

Collection/Call #: Rare Books HV248 .H17

Milwaukee Branch of the Industrial Workers of the World, Incarcerated Worker Organizing Committee. Reproduction of page 3 from Voices from Behind Wisconsin Prison Gates, Issue 1, May 2016.

United States. Constitution. 13th Amendment. Signed by Abraham Lincoln and Members of Congress, 1865.

Gift of Nicholas H. and Marguerite Lilly Noyes

Passed by Congress on January 31, 1865 and ratified by the states on December 6, 1865, the 13th Amendment to the Constitution formally abolished slavery in the United States but it left the door open for involuntary servitude as a form of punishment. It reads, “Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction” (emphasis added).

Cornell’s Thirteenth Amendment manuscript is one of 14 souvenir or commemorative copies of the Amendment signed by Lincoln and 150 of the senators and representatives who voted for it.

Collection/Call #: Rare Books E173.N95 pt.17++++