Global Perspectives

When we speak of globalization, we often think of the “free market” and of the export of technology and knowledge from wealthy countries to the global south. In the case of cotton textiles, images are conjured of the Southern United States, maybe a Northern textile mill, and the movement to other countries during the 20th century. The roots of textile production are much deeper and more complicated than that. The origins of cotton fiber are believed to be in the Indus River Valley in modern-day Pakistan in 3000 B.C., but there is evidence of cotton fiber and cloth in what is now Mexico as early as 5000 B.C. It was the Industrial Revolution that allowed Britain to overtake India as the world’s largest cotton textile producer in the 1760s. And in 1933, World War I-related declines in exports from Britain and a 24-hour factory system allowed Japan to take the title. In 2022, that standing belongs to China, with India in second.

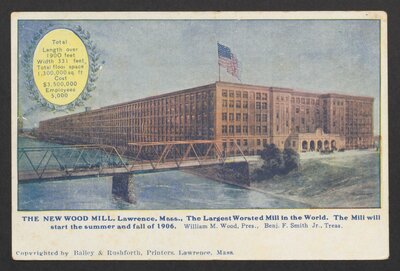

Throughout the 19th and 20th centuries, textiles using patterns and dyes that had been created for thousands of years in places like China, Iraq, West Africa, Indonesia, and India were appropriated and mass-produced in industrialized countries. In the Northern U.S., the industrialization of the textile industry came to a peak after World War II as consumer desires changed and industrialization was encouraged around the world. The industry magnates pushed for protections from foreign products, but they were fighting a rising tide. A symbol of this wave can be found in the Wood Worsted Mill. Constructed in Lawrence, Massachusetts, in 1905, the mill was considered the largest building of its kind in the world at the time, and was the newest mill built for the American Woolen Company, itself the largest woolen manufacturer in the world. As the demand and price for wool fell drastically, most of the once grand mill was demolished in 1956, after lasting just over half a century.

Most of the industry in the Northern U.S. would move South by the mid-20th century, and move out of the U.S. entirely by the end of the century, as it searched for fewer regulations and cheaper sources of non-unionized labor.

Bailey and Rushforth. Postcard of New Wood Mill, ca. 1906.

On loan from the Kheel Center for Labor-Management Documentation & Archives

Collection/Call #: 6524/005P

Search CUL catalog for this item/collection

Henry S. Anthony & Company. Auction catalog, Wood & Ayer Mills, 1956.

On loan from the Kheel Center for Labor-Management Documentation & Archives

Collection/Call #: 6605/001

Unknown photographer. Destruction of Wood Mill, American Woolen Company, 1958.

Notice the demolition of the mill just behind the male figure. The same clock appears here and on the postcard.

On loan from the Kheel Center for Labor-Management Documentation & Archives

Collection/Call #: 6524/005P

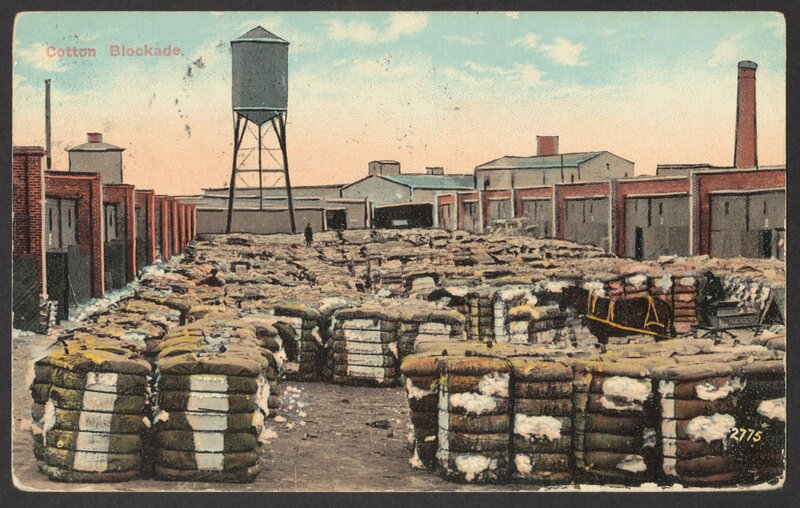

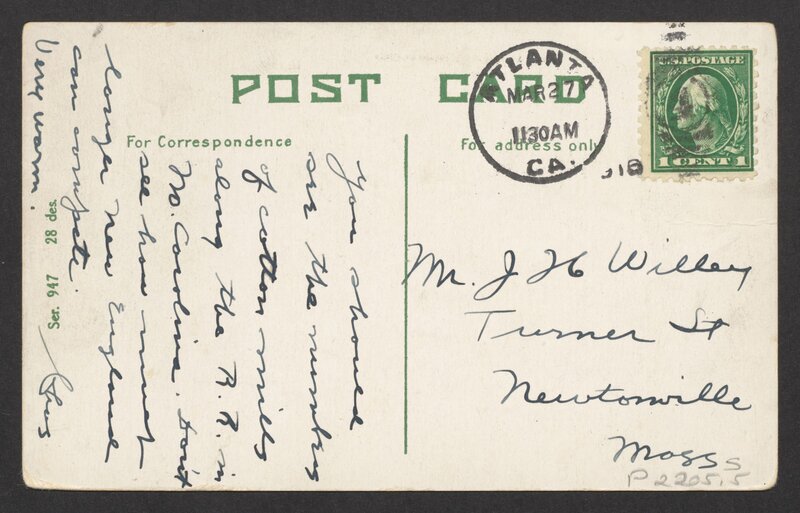

Unknown photographer. Cotton Blockade, ca. 1916-1918.

Handwriting reads: "You should see the numbers of cotton mills along the R.R. in No. Carolina. Don't see how much longer New England can compete. Very warm. Chas." By the 1920s the Southern U.S. would overtake the North in textile production.

On loan from the Kheel Center for Labor-Management Documentation & Archives

Collection/Call #: 6524/005P

Communist Party, New Bedford, Massachusetts. "The Truth about the South and What it Means to You!" flyer, 1949.

The lack of regulations and a non-unionized workforce were major draws for textile mill owners in their decision to move South. They used racial lines to keep overall wages down and discourage organization among Black and white workers. Similar tactics had been used between immigrant communities in the North.

On loan from the Kheel Center for Labor-Management Documentation & Archives

Collection/Call #: 6524/004 G

Eastland Press Service. Textile India, 1954.

A catalog listing textile companies in India and their products. It also contains articles about the history of the industrialization of India.

On loan from the Kheel Center for Labor-Management Documentation & Archives

Collection/Call #: HD9886 I4 T4

Unknown photographer. Textile mill in India showing warper with creel behind, ca. 1900.

An example of early industrialization in India.

On loan from the Kheel Center for Labor-Management Documentation & Archives

Collection/Call #: 6524/002 P

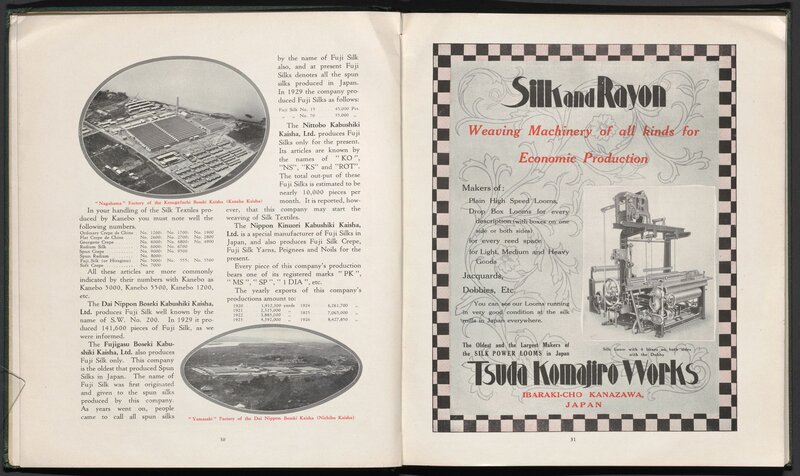

Kobe Export Silk Goods Guild. Japanese Silks and Rayons: Guide Book for Importers, Merchants, & Consumers of the World, 1934.

A catalog listing Japanese mills and their products. While Japan had overtaken Britain as the world’s top cotton textile producer the year before, it also was a leading producer of silk and rayon textiles.

On loan from the Kheel Center for Labor-Management Documentation & Archives

Collection/Call #: HD9916 J3 K8 1931

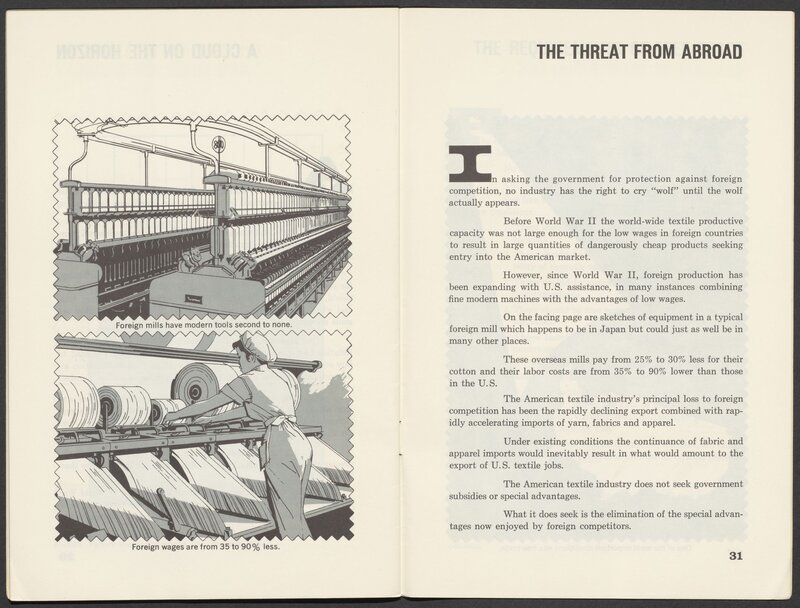

The American Economic Foundation (publisher). “The Threat from Abroad,” in How we Live in Textiles. 1960.

On loan from the Kheel Center for Labor-Management Documentation & Archives

Collection/Call #: HD9855.H68 1960

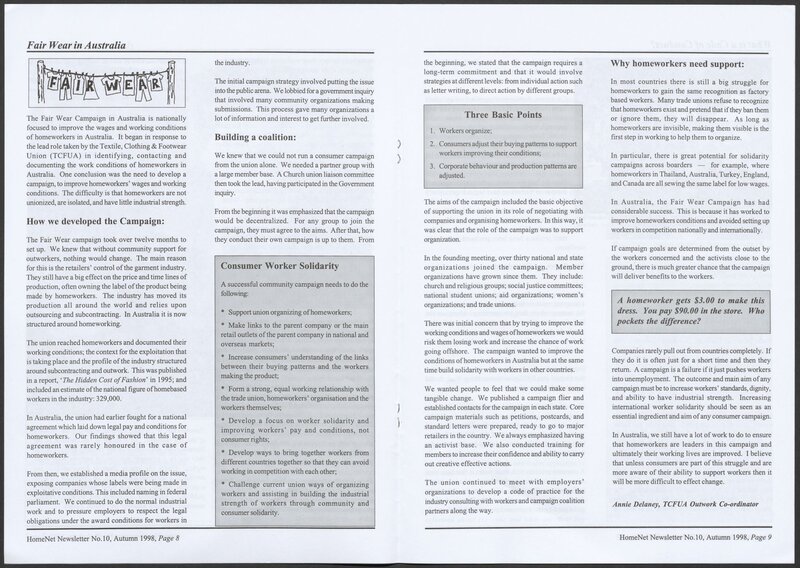

International Network of Homebased Workers. HomeNet, Autumn 1998.

This newsletter highlights some of the labor organizing work that continues for textile workers around the world.

On loan from the Kheel Center for Labor-Management Documentation & Archives

Collection/Call #: 6000/027 PUBS

Unknown publisher. Free Trade/Protection/Which? Poster, 1888.

In this poster from the 1888 election between Benjamin Harrison and Grover Cleveland, Harrison is shown as protecting American trade and keeping industry and prosperity in the U.S. through tariffs. Cleveland, who promoted a reduction in tariffs to lower costs to consumers, is shown as a proponent of free trade, bringing foreign goods and poverty for U.S. workers. Cleveland would win the popular vote but lose the election, a feat that would not occur again for another 112 years.

On loan from the Kheel Center for Labor-Management Documentation & Archives

Collection/Call #: 6524/004 G